10 PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

PUNCH'S IMAGINARY CONVERSATIONS.

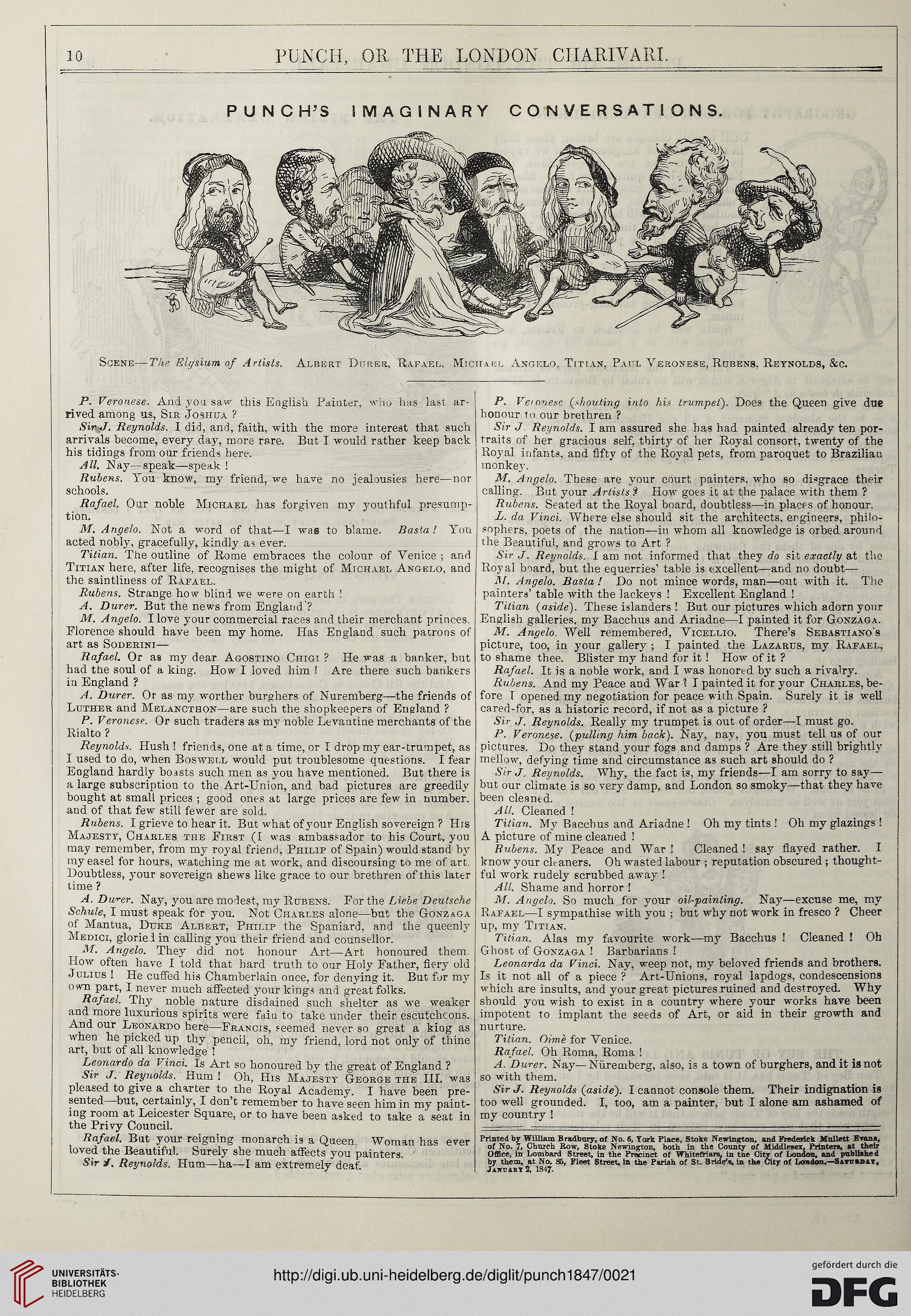

Scene—The Elysium of Artists. Albert Durer, Rafael, Michael Angelo, Titian, Paul Veronese, Rubens, Reynolds, &c.

P. Veronese. And yoa saw this English Painter, who has last ar-

rived among us, Sir Joshua ?

SiiyJ. Reynolds. I did, and, faith, with the more interest that such

arrivals become, every day, more rare. But I would rather keep hack

his tidings from our friends here.

All. Nay—speak—speak !

Rubens. You know, my friend, we have no jealousies here—nor

schools.

Rafael. Oar noble Michael has forgiven my youthful presump-

tion.

M. Angelo. Not a word of that—I was to blame. Basta ! You

acted nobly, gracefully, kindly as ever.

Titian. The outline of Rome embraces the colour of Venice ; and

Titian here, after life, recognises the might of Michael Angelo, and

the saintliuess of Rafael.

Rubens. Strange how blind we were on earth !

A. Durer. Bat the news from England'?

M. Angelo. I love your commercial races and their merchant princes.

Florence should have been my home. Has England such patrons of

art as Soderini—

Rafael. Or as my dear Agostino Chigi ? He was a banker, but

had the soul of a king. How I loved him ! Are there such bankers

in England ?

A. Durer. Or as my worthier burghers of Nuremberg—the friends of

Luther and Meeancthon—are such the shopkeepers of England ?

P. Veronese. Or such traders as mv noble Levantine merchants of the

Rialto ?

Reynolds. Hush ! friends, one at a time, or I drop my ear-trumpet, as

I used to do, when Bosweld would put troublesome questions. I fear

England hardly boasts such men as you have mentioned. Bat there is

a large subscription to the Art-Union, and bad pictures are greedily

bought at small prices ; good ones at large prices are few in number,

and of that few still fewer are sold.

Rubens. I grieve to hear it. Bat what of your English sovereign ? His

Majesty, Charles the First (I was ambassador to his Court, you

may remember, from my royal friend, Philip of Spain) would stand by

my easel for hours, watching me at work, and discoursing to me of art.

Doubtless, your sovereign shews like grace to our brethren of this later

time ?

A. Du^er. Nay, you are modest, my Rubens. For the Liebe Deutsche

Schule, I must speak for you. Not Charles alone—but the Gonzaga

of Mantua, Duke Albert, Philip the Spaniard, and the queenly

Medici, gloried in calling you their friend and counsellor.

M. Angelo. They did not honour Art—Art honoured them.

How often have I told that hard truth to our Holy Father, fiery old

Julius ! He cuffed his Chamberlain once, for denying it. But for my

own part, I never much affected your kings and great folks.

Rafael. Thy noble nature disdained such shelter as we weaker

and more luxurious spirits were fain to take under their escutcheons.

And our Leonardo here—Francis, seemed never so great a king as

when he picked up thy pencil, oh, my friend, lord not only of thine

art, hut of all knowledge !

Leonardo da Vinci. Is Art so honoured by the great of England ?

Sir J. Reynolds. Hum ! Oh, His Majesty George the III. was

pleased to give a charter to the Royal Academy. I have been pre-

sented—but, certainly, I don't remember to have seen him in my paint-

ing room at Leicester Square, or to have been asked to take a seat in

the Privy Council.

Rafael. But your reigning monarch is a Queen. Woman has ever

loved the Beautiful. Surely she much affects you painters.

Sir /. Reynolds. Hum—ha—I am extremely deaf.

P. Ve/onesc (shouting into hi.< trumpet). Does the Queen give due

honour To our brethren ?

Sir J. Reynolds. I am assured she has had painted already ten por-

traits of her gracious self, thirty of her Royal consort, twenty of the

Royal infants, and fifty of the Royal pets, from paroquet to Brazilian

monkey.

M. Angelo. These are your court painters, who so disgrace their

calling. But your Artists * How goes it at the palace with them ?

Rubens. Seated at the Royal board, doubtless—in places of honour.

L. da Vinci. Where else should sit the architects, engineers, philo-

sophers, poets of the nation—in whom all knowledge is orbed around

ihe Beautiful, and grows to Art ?

Sir J. Reynolds. I am not informed that they do sit exactly at the

Royal b^rd, but the equerries' table is excellent—and no doubt—

M. Angelo. Basta ! Do not mince words, man—out with it. The

painters' table with the lackeys ! Excellent England !

Titian (aside). These islanders ! But our pictures which adorn your

English galleries, my Bacchus and Ariadne—I painted it for Gonzaga.

M. Angelo. Well remembered, Vicellio. There's Sebastiano's

picture, too, in your gallery ; I painted the Lazarus, my Rafael,

to shame thee. Blister my hand for it! How of it ?

Rafael. It is a noble work, and I was honored by such a rivalry.

Rubens. And my Peace and War 1 I painted it for your Charles, be-

fore I opened my negotiation for peace with Spain. Surely it is well

cared-for, as a historic record, if not as a picture ?

Sir J. Reynolds. Really my trumpet is out of order—I must go.

P. Veronese, (pulling him back). Nay, nay, you must tell us of our

pictures. Do they stand your fogs and damps ? Are they still brightly

mellow, defying time and circumstance as such art should do ?

Sir J. Reynolds. Why, the fact is, my friends—I am sorry to say—

but our climate is so very damp, and London so smoky—that they have

been cleaned.

All. Cleaned !

Titian. My Bacchus and Ariadne ! Oh my tints ! Oh my glazings !

A picture of mine cleaned !

Rubens. My Peace and War ! Cleaned ! say flayed rather. I

know your cleaners. Oh wasted labour ; reputation obscured ; thought-

ful work rudely scrubbed away !

All. Shame and horror !

M. Angelo. So much for your oil-painting. Nay—excuse me, my

Rafael—I sympathise with you ; but why not work in fresco ? Cheer

up, my Titian.

Titian. Alas my favourite work—my Bacchus ! Cleaned ! Oh

Ghost of Gonzaga ! Barbarians !

Leonarda da Vinci. Nay, weep not, my beloved friends and brothers.

Is it not all of a piece ? Art-Unions, royal lapdogs, condescensions

which are insults, and your great pictures ruined and destroyed. Why

should you wish to exist in a country where your works have been

impotent to implant the seeds of Art, or aid in their growth and

nurture.

Titian. Dime for Venice.

Rafael. Oh Roma, Roma !

A. Durer. Nay—Nuremberg, also, is a town of burghers, and it is not

so with them.

Sir J. Reynolds (aside). I cannot console them Their indignation is

too well grounded. I, too, am a painter, but I alone am ashamed of

my country !

Printed by William Bradbury, of No. 6, York Place, Stoke Newinirton, and Frederick Mullett Erana,

of No. 7. Church Row, Stoke Newingfton, both in the Comity of Middlesex, Printer*, at their

Office, in Lombard Street, in the Precinct of Whitefriars, in the City of London, and published

by them, at No. 85, Fleet Street, in the Pariah of St. Bride's, in the City of London.—SaruanaT,

JiifcaaTS, 1847.

PUNCH'S IMAGINARY CONVERSATIONS.

Scene—The Elysium of Artists. Albert Durer, Rafael, Michael Angelo, Titian, Paul Veronese, Rubens, Reynolds, &c.

P. Veronese. And yoa saw this English Painter, who has last ar-

rived among us, Sir Joshua ?

SiiyJ. Reynolds. I did, and, faith, with the more interest that such

arrivals become, every day, more rare. But I would rather keep hack

his tidings from our friends here.

All. Nay—speak—speak !

Rubens. You know, my friend, we have no jealousies here—nor

schools.

Rafael. Oar noble Michael has forgiven my youthful presump-

tion.

M. Angelo. Not a word of that—I was to blame. Basta ! You

acted nobly, gracefully, kindly as ever.

Titian. The outline of Rome embraces the colour of Venice ; and

Titian here, after life, recognises the might of Michael Angelo, and

the saintliuess of Rafael.

Rubens. Strange how blind we were on earth !

A. Durer. Bat the news from England'?

M. Angelo. I love your commercial races and their merchant princes.

Florence should have been my home. Has England such patrons of

art as Soderini—

Rafael. Or as my dear Agostino Chigi ? He was a banker, but

had the soul of a king. How I loved him ! Are there such bankers

in England ?

A. Durer. Or as my worthier burghers of Nuremberg—the friends of

Luther and Meeancthon—are such the shopkeepers of England ?

P. Veronese. Or such traders as mv noble Levantine merchants of the

Rialto ?

Reynolds. Hush ! friends, one at a time, or I drop my ear-trumpet, as

I used to do, when Bosweld would put troublesome questions. I fear

England hardly boasts such men as you have mentioned. Bat there is

a large subscription to the Art-Union, and bad pictures are greedily

bought at small prices ; good ones at large prices are few in number,

and of that few still fewer are sold.

Rubens. I grieve to hear it. Bat what of your English sovereign ? His

Majesty, Charles the First (I was ambassador to his Court, you

may remember, from my royal friend, Philip of Spain) would stand by

my easel for hours, watching me at work, and discoursing to me of art.

Doubtless, your sovereign shews like grace to our brethren of this later

time ?

A. Du^er. Nay, you are modest, my Rubens. For the Liebe Deutsche

Schule, I must speak for you. Not Charles alone—but the Gonzaga

of Mantua, Duke Albert, Philip the Spaniard, and the queenly

Medici, gloried in calling you their friend and counsellor.

M. Angelo. They did not honour Art—Art honoured them.

How often have I told that hard truth to our Holy Father, fiery old

Julius ! He cuffed his Chamberlain once, for denying it. But for my

own part, I never much affected your kings and great folks.

Rafael. Thy noble nature disdained such shelter as we weaker

and more luxurious spirits were fain to take under their escutcheons.

And our Leonardo here—Francis, seemed never so great a king as

when he picked up thy pencil, oh, my friend, lord not only of thine

art, hut of all knowledge !

Leonardo da Vinci. Is Art so honoured by the great of England ?

Sir J. Reynolds. Hum ! Oh, His Majesty George the III. was

pleased to give a charter to the Royal Academy. I have been pre-

sented—but, certainly, I don't remember to have seen him in my paint-

ing room at Leicester Square, or to have been asked to take a seat in

the Privy Council.

Rafael. But your reigning monarch is a Queen. Woman has ever

loved the Beautiful. Surely she much affects you painters.

Sir /. Reynolds. Hum—ha—I am extremely deaf.

P. Ve/onesc (shouting into hi.< trumpet). Does the Queen give due

honour To our brethren ?

Sir J. Reynolds. I am assured she has had painted already ten por-

traits of her gracious self, thirty of her Royal consort, twenty of the

Royal infants, and fifty of the Royal pets, from paroquet to Brazilian

monkey.

M. Angelo. These are your court painters, who so disgrace their

calling. But your Artists * How goes it at the palace with them ?

Rubens. Seated at the Royal board, doubtless—in places of honour.

L. da Vinci. Where else should sit the architects, engineers, philo-

sophers, poets of the nation—in whom all knowledge is orbed around

ihe Beautiful, and grows to Art ?

Sir J. Reynolds. I am not informed that they do sit exactly at the

Royal b^rd, but the equerries' table is excellent—and no doubt—

M. Angelo. Basta ! Do not mince words, man—out with it. The

painters' table with the lackeys ! Excellent England !

Titian (aside). These islanders ! But our pictures which adorn your

English galleries, my Bacchus and Ariadne—I painted it for Gonzaga.

M. Angelo. Well remembered, Vicellio. There's Sebastiano's

picture, too, in your gallery ; I painted the Lazarus, my Rafael,

to shame thee. Blister my hand for it! How of it ?

Rafael. It is a noble work, and I was honored by such a rivalry.

Rubens. And my Peace and War 1 I painted it for your Charles, be-

fore I opened my negotiation for peace with Spain. Surely it is well

cared-for, as a historic record, if not as a picture ?

Sir J. Reynolds. Really my trumpet is out of order—I must go.

P. Veronese, (pulling him back). Nay, nay, you must tell us of our

pictures. Do they stand your fogs and damps ? Are they still brightly

mellow, defying time and circumstance as such art should do ?

Sir J. Reynolds. Why, the fact is, my friends—I am sorry to say—

but our climate is so very damp, and London so smoky—that they have

been cleaned.

All. Cleaned !

Titian. My Bacchus and Ariadne ! Oh my tints ! Oh my glazings !

A picture of mine cleaned !

Rubens. My Peace and War ! Cleaned ! say flayed rather. I

know your cleaners. Oh wasted labour ; reputation obscured ; thought-

ful work rudely scrubbed away !

All. Shame and horror !

M. Angelo. So much for your oil-painting. Nay—excuse me, my

Rafael—I sympathise with you ; but why not work in fresco ? Cheer

up, my Titian.

Titian. Alas my favourite work—my Bacchus ! Cleaned ! Oh

Ghost of Gonzaga ! Barbarians !

Leonarda da Vinci. Nay, weep not, my beloved friends and brothers.

Is it not all of a piece ? Art-Unions, royal lapdogs, condescensions

which are insults, and your great pictures ruined and destroyed. Why

should you wish to exist in a country where your works have been

impotent to implant the seeds of Art, or aid in their growth and

nurture.

Titian. Dime for Venice.

Rafael. Oh Roma, Roma !

A. Durer. Nay—Nuremberg, also, is a town of burghers, and it is not

so with them.

Sir J. Reynolds (aside). I cannot console them Their indignation is

too well grounded. I, too, am a painter, but I alone am ashamed of

my country !

Printed by William Bradbury, of No. 6, York Place, Stoke Newinirton, and Frederick Mullett Erana,

of No. 7. Church Row, Stoke Newingfton, both in the Comity of Middlesex, Printer*, at their

Office, in Lombard Street, in the Precinct of Whitefriars, in the City of London, and published

by them, at No. 85, Fleet Street, in the Pariah of St. Bride's, in the City of London.—SaruanaT,

JiifcaaTS, 1847.

Werk/Gegenstand/Objekt

Titel

Titel/Objekt

Punch's imaginary conversations

Weitere Titel/Paralleltitel

Serientitel

Punch

Sachbegriff/Objekttyp

Inschrift/Wasserzeichen

Aufbewahrung/Standort

Aufbewahrungsort/Standort (GND)

Inv. Nr./Signatur

H 634-3 Folio

Objektbeschreibung

Objektbeschreibung

Bildunterschrift: The Eylsium of Artists. Albert Durer, Rafael, Michael Angelo, Titian, Paul Veronese, Rubens, Reynolds, &c.

Maß-/Formatangaben

Auflage/Druckzustand

Werktitel/Werkverzeichnis

Herstellung/Entstehung

Künstler/Urheber/Hersteller (GND)

Entstehungsdatum

um 1847

Entstehungsdatum (normiert)

1842 - 1852

Entstehungsort (GND)

Auftrag

Publikation

Fund/Ausgrabung

Provenienz

Restaurierung

Sammlung Eingang

Ausstellung

Bearbeitung/Umgestaltung

Thema/Bildinhalt

Thema/Bildinhalt (GND)

Literaturangabe

Rechte am Objekt

Aufnahmen/Reproduktionen

Künstler/Urheber (GND)

Reproduktionstyp

Digitales Bild

Rechtsstatus

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Creditline

Punch, 12.1847, January to June, 1847, S. 10

Beziehungen

Erschließung

Lizenz

CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication

Rechteinhaber

Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg