76

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

BROUGHAM'S POSES PLASTIQUES.

Wje have had, during the last year or two, a variety of Professors

whose attainments have consisted of an aptitude for throwing them-

selves and others into all sorts of different attitudes. We have seen

Professor Risley with his sons standing on the palm of their parent,

who gets his children off his hands in the most astonishing manner.

We have witnessed tntortilationists of every description, who have com •

bined the twistaboutitiveness of the eel, with the jumpupeightfeethigh-

ativeness of the antelope. We have heard of, though we have not

cared to see, the half-dozen Venuses who have been nightly rising

from the sea during the last six months in every quarter of the

metropolis.

But the greatest wonder of all in the pose plastique line are the mar-

vellous entortilations of Henry Lord Brougham. He has all the

elasticity of Indian-rubber, with more expression ; and the play of his

features, down to the very tip of his nose, is absolutely wonderful.

The very best of the Venuses rising from the sea is nothing compared

with the Ex-Chancellor rising from the woolsack. Cincinnati's tying

his sandal—by the bye, how was it he had it so frequently dangling

about his heels as to make his tying it a personal peculiarity by which

he is known to posterity ?—was a mere fool to Brougham fastening

his high-low.

But the most astonishing part of the noble Lord's performances is

the series of attitudes into which he throws himself during a speech in

the House of Lords ; for however brief the oration may be, he contrives

to illustrate it with a rapid succession of elective tableaux, as unique

as they are graceful. He not only suits the action to the word, when

he speaks himself; but while any one else is addressing the House,

Loud Brougham finds for every word a suitable action : he is the

great pantomime peer, or, to use a legal expression, he is a tremendous

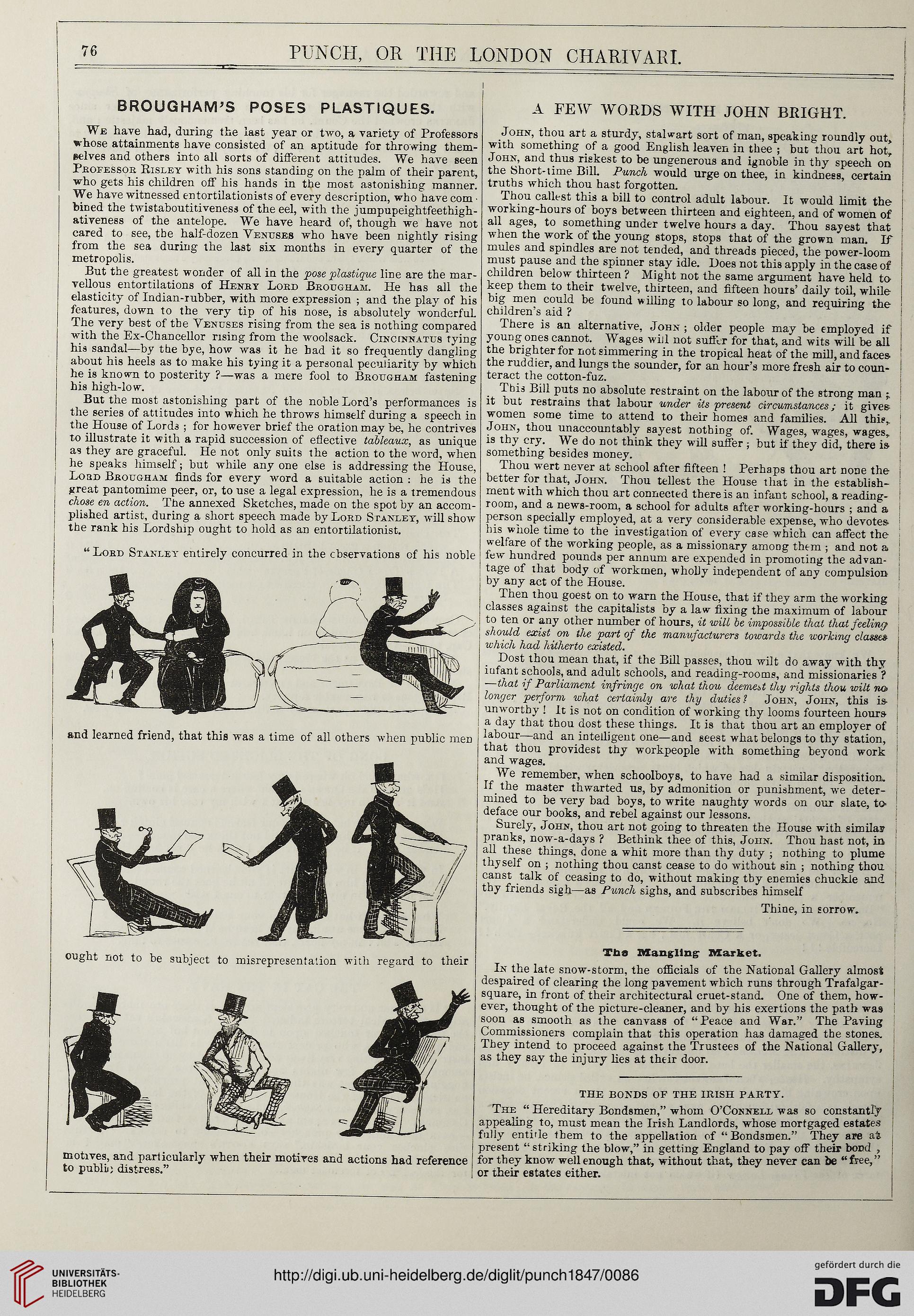

chose en action. The annexed Sketches, made on the spot by an accom-

plished artist, during a short speech made by Lord Stanley, will show

the rank his Lordship ought to hold as an entortilationist.

"Lord Stanley entirely concurred in the observations of his noble

and learned friend, that this was a time of all others when public men

ought not to be subject to misrepresentation with regard to their

motives, and particularly when their motires and actions had reference

to publii; distress."

A FEW WORDS WITH JOHN BRIGHT.

John, thou art a sturdy, stalwart sort of man, speaking roundly out,

with something of a good English leaven in thee ; but thou art hot,

John, and thus riskest to be ungenerous and ignoble in thy speech on

the Short-time Bill. Punch would urge on thee, in kindness, certain

truths which thou hast forgotten.

Thou callest this a bill to control adult labour. It would limit the

working-hours of boys between thirteen and eighteen, and of women of

all ages, to something under twelve hours a day. Thou sayest that

when the work of the young stops, stops that of the grown man. If

mules and spindles are not tended, and threads pieced, the power-loom

must pause and the spinner stay idle. Does not this apply in the case of

children below thirteen ? Might not the same argument have held to

keep them to their twelve, thirteen, and fifteen hours' daily toil, while

big men could be found willing to labour so long, and requiring the

children's aid ?

There is an alternative, John ; older people may be employed if

young ones cannot. Wages will not suffer for that, and wits will be all

the brighter for not simmering in the tropical heat of the mill, and faces- ;

the ruddier, and lungs the sounder, for an hour's more fresh air to coun-

teract the cotton-fuz.

This Bill puts no absolute restraint on the labour of the strong man

it but restrains that labour under its present circumstances; it gives-

women some time to attend to their homes and families. All tbi?, !

John, thou unaccountably sayest nothing of. Wages, wages, wages, |

is thy cry. We do not think they will suffer ; but if they did, there is-

something besides money.

Thou wert never at school after fifteen ! Perhaps thou art none the

better for that, John. Thou tellest the House that in the establish-

ment with which thou art connected there is an infant school, a reading-

room, and a news-room, a school for adults after working-hours ; and a

person specially employed, at a very considerable expense, who devotes-

his whole time to the investigation of every case which can affect the

welfare of the working people, as a missionary among them ; and not a

few hundred pounds per annum are expended in promoting the advan-

tage of that body of workmen, wholly independent of any compulsion

by any act of the House.

Then thou goest on to warn the House, that if they arm the working

classes against the capitalists by a law fixing the maximum of labour

to ten or any other number of hours, it will be impossible thai that feeling

should exist on the part of the manufacturers towards the working classes

which had hitherto existed.

Dost thou mean that, if the Bill passes, thou wilt do away with thy

iufant schools, and adult schools, and reading-rooms, and missionaries ?

—that if Parliament infringe on what thou deemeU thy rights thou wilt no

longer perform what certainly are thy duties 1 John, John, this is-

unworthy ! It is not on condition of working thy looms fourteen hours

a day that thou dost these things. It is that thou art an employer of

labour—and an intelligent one—and seest what belongs to thy station, :

that thou providest thy workpeople with something beyond work

and wages.

We remember, when schoolboys, to have had a similar disposition.

If the master thwarted us, by admonition or punishment, we deter-

mined to be very bad boys, to write naughty words on our slate, to-

deface our books, and rebel against our lessons.

Surely, John, thou art not going to threaten the House with similar

pranks, now-a-days ? Bethink thee of this, John. Thou hast not, in

all these things, done a whit more than thy duty ; nothing to plume

thyself on ; nothing thou canst cease to do without sin ; nothing thou

canst talk of ceasing to do, without making tby enemies chuckle and |

thy friends sigh—as Punch sighs, and subscribes himself

Thine, in sorrow.

-— ■

--------

Tna Mangling: Market.

In the late snow-storm, the officials of the National Gallery almost

despaired of clearing the long pavement which runs through Trafalgar- ■

square, in front of their architectural cruet-stand. One of them, how-

ever, thought of the picture-cleaner, and by his exertions the path was

soon as smooth as the canvass of "Peace and War." The Paving

Commissioners complain that this operation has damaged the stones.

They intend to proceed against the Trustees of the National Gallery,

as they say the injury lies at their door.

THE BONDS OF THE IRISH PARTY.

The " Hereditary Bondsmen," whom O'Connell was so constantly

appealing to, must mean the Irish Landlords, whose mortgaged estates

fully entitle them to the appellation of "Bondsmen." They are at

present "striking the blow," in getting England to pay off their boDd ,

for they know well enough that, without that, they never can be "free,"

or their estates either.

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

BROUGHAM'S POSES PLASTIQUES.

Wje have had, during the last year or two, a variety of Professors

whose attainments have consisted of an aptitude for throwing them-

selves and others into all sorts of different attitudes. We have seen

Professor Risley with his sons standing on the palm of their parent,

who gets his children off his hands in the most astonishing manner.

We have witnessed tntortilationists of every description, who have com •

bined the twistaboutitiveness of the eel, with the jumpupeightfeethigh-

ativeness of the antelope. We have heard of, though we have not

cared to see, the half-dozen Venuses who have been nightly rising

from the sea during the last six months in every quarter of the

metropolis.

But the greatest wonder of all in the pose plastique line are the mar-

vellous entortilations of Henry Lord Brougham. He has all the

elasticity of Indian-rubber, with more expression ; and the play of his

features, down to the very tip of his nose, is absolutely wonderful.

The very best of the Venuses rising from the sea is nothing compared

with the Ex-Chancellor rising from the woolsack. Cincinnati's tying

his sandal—by the bye, how was it he had it so frequently dangling

about his heels as to make his tying it a personal peculiarity by which

he is known to posterity ?—was a mere fool to Brougham fastening

his high-low.

But the most astonishing part of the noble Lord's performances is

the series of attitudes into which he throws himself during a speech in

the House of Lords ; for however brief the oration may be, he contrives

to illustrate it with a rapid succession of elective tableaux, as unique

as they are graceful. He not only suits the action to the word, when

he speaks himself; but while any one else is addressing the House,

Loud Brougham finds for every word a suitable action : he is the

great pantomime peer, or, to use a legal expression, he is a tremendous

chose en action. The annexed Sketches, made on the spot by an accom-

plished artist, during a short speech made by Lord Stanley, will show

the rank his Lordship ought to hold as an entortilationist.

"Lord Stanley entirely concurred in the observations of his noble

and learned friend, that this was a time of all others when public men

ought not to be subject to misrepresentation with regard to their

motives, and particularly when their motires and actions had reference

to publii; distress."

A FEW WORDS WITH JOHN BRIGHT.

John, thou art a sturdy, stalwart sort of man, speaking roundly out,

with something of a good English leaven in thee ; but thou art hot,

John, and thus riskest to be ungenerous and ignoble in thy speech on

the Short-time Bill. Punch would urge on thee, in kindness, certain

truths which thou hast forgotten.

Thou callest this a bill to control adult labour. It would limit the

working-hours of boys between thirteen and eighteen, and of women of

all ages, to something under twelve hours a day. Thou sayest that

when the work of the young stops, stops that of the grown man. If

mules and spindles are not tended, and threads pieced, the power-loom

must pause and the spinner stay idle. Does not this apply in the case of

children below thirteen ? Might not the same argument have held to

keep them to their twelve, thirteen, and fifteen hours' daily toil, while

big men could be found willing to labour so long, and requiring the

children's aid ?

There is an alternative, John ; older people may be employed if

young ones cannot. Wages will not suffer for that, and wits will be all

the brighter for not simmering in the tropical heat of the mill, and faces- ;

the ruddier, and lungs the sounder, for an hour's more fresh air to coun-

teract the cotton-fuz.

This Bill puts no absolute restraint on the labour of the strong man

it but restrains that labour under its present circumstances; it gives-

women some time to attend to their homes and families. All tbi?, !

John, thou unaccountably sayest nothing of. Wages, wages, wages, |

is thy cry. We do not think they will suffer ; but if they did, there is-

something besides money.

Thou wert never at school after fifteen ! Perhaps thou art none the

better for that, John. Thou tellest the House that in the establish-

ment with which thou art connected there is an infant school, a reading-

room, and a news-room, a school for adults after working-hours ; and a

person specially employed, at a very considerable expense, who devotes-

his whole time to the investigation of every case which can affect the

welfare of the working people, as a missionary among them ; and not a

few hundred pounds per annum are expended in promoting the advan-

tage of that body of workmen, wholly independent of any compulsion

by any act of the House.

Then thou goest on to warn the House, that if they arm the working

classes against the capitalists by a law fixing the maximum of labour

to ten or any other number of hours, it will be impossible thai that feeling

should exist on the part of the manufacturers towards the working classes

which had hitherto existed.

Dost thou mean that, if the Bill passes, thou wilt do away with thy

iufant schools, and adult schools, and reading-rooms, and missionaries ?

—that if Parliament infringe on what thou deemeU thy rights thou wilt no

longer perform what certainly are thy duties 1 John, John, this is-

unworthy ! It is not on condition of working thy looms fourteen hours

a day that thou dost these things. It is that thou art an employer of

labour—and an intelligent one—and seest what belongs to thy station, :

that thou providest thy workpeople with something beyond work

and wages.

We remember, when schoolboys, to have had a similar disposition.

If the master thwarted us, by admonition or punishment, we deter-

mined to be very bad boys, to write naughty words on our slate, to-

deface our books, and rebel against our lessons.

Surely, John, thou art not going to threaten the House with similar

pranks, now-a-days ? Bethink thee of this, John. Thou hast not, in

all these things, done a whit more than thy duty ; nothing to plume

thyself on ; nothing thou canst cease to do without sin ; nothing thou

canst talk of ceasing to do, without making tby enemies chuckle and |

thy friends sigh—as Punch sighs, and subscribes himself

Thine, in sorrow.

-— ■

--------

Tna Mangling: Market.

In the late snow-storm, the officials of the National Gallery almost

despaired of clearing the long pavement which runs through Trafalgar- ■

square, in front of their architectural cruet-stand. One of them, how-

ever, thought of the picture-cleaner, and by his exertions the path was

soon as smooth as the canvass of "Peace and War." The Paving

Commissioners complain that this operation has damaged the stones.

They intend to proceed against the Trustees of the National Gallery,

as they say the injury lies at their door.

THE BONDS OF THE IRISH PARTY.

The " Hereditary Bondsmen," whom O'Connell was so constantly

appealing to, must mean the Irish Landlords, whose mortgaged estates

fully entitle them to the appellation of "Bondsmen." They are at

present "striking the blow," in getting England to pay off their boDd ,

for they know well enough that, without that, they never can be "free,"

or their estates either.

Werk/Gegenstand/Objekt

Titel

Titel/Objekt

Brougham's poses plastiques

Weitere Titel/Paralleltitel

Serientitel

Punch

Sachbegriff/Objekttyp

Inschrift/Wasserzeichen

Aufbewahrung/Standort

Aufbewahrungsort/Standort (GND)

Inv. Nr./Signatur

H 634-3 Folio

Objektbeschreibung

Maß-/Formatangaben

Auflage/Druckzustand

Werktitel/Werkverzeichnis

Herstellung/Entstehung

Entstehungsdatum

um 1847

Entstehungsdatum (normiert)

1842 - 1852

Entstehungsort (GND)

Auftrag

Publikation

Fund/Ausgrabung

Provenienz

Restaurierung

Sammlung Eingang

Ausstellung

Bearbeitung/Umgestaltung

Thema/Bildinhalt

Thema/Bildinhalt (GND)

Literaturangabe

Rechte am Objekt

Aufnahmen/Reproduktionen

Künstler/Urheber (GND)

Reproduktionstyp

Digitales Bild

Rechtsstatus

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Creditline

Punch, 12.1847, January to June, 1847, S. 76

Beziehungen

Erschließung

Lizenz

CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication

Rechteinhaber

Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg