266

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

THE COMIC BLACKSTONE-

chapter the sixth.—of the king's (or queen's) duties.

We now come to the duties of the sovereign, which will form a very

short chapter, though the prerogative which comes next will not be so

briefly disposed of. The principal duty of the sovereign is to govern

according to law, which is no such easy matter, when it is considered

how frightfully uncertain the law is, and how difficult it must be to govern

according to anything so horridly dubious. Bracton, who wrote in the

time of Henry the Third—and a nice time he had of it—declares that the

king is subject to nothing on earth ; but Henry the Eighth was subject

to the gout, and Queen Anne is thought to have been subject to chilblains.

Fortescue, who was the Archbold of his day, and was always bringing out

law books, tells us the important fact that " the king takes an oath at his

coronation, and is bound to keep it but semble, say we, that if he did

not choose to keep it he could not be had up at the Old Bailey for perjury.

Fortescue deserves " a pinch for stale news," which was the schoolboy

penalty, in our time, for very late intelligence.

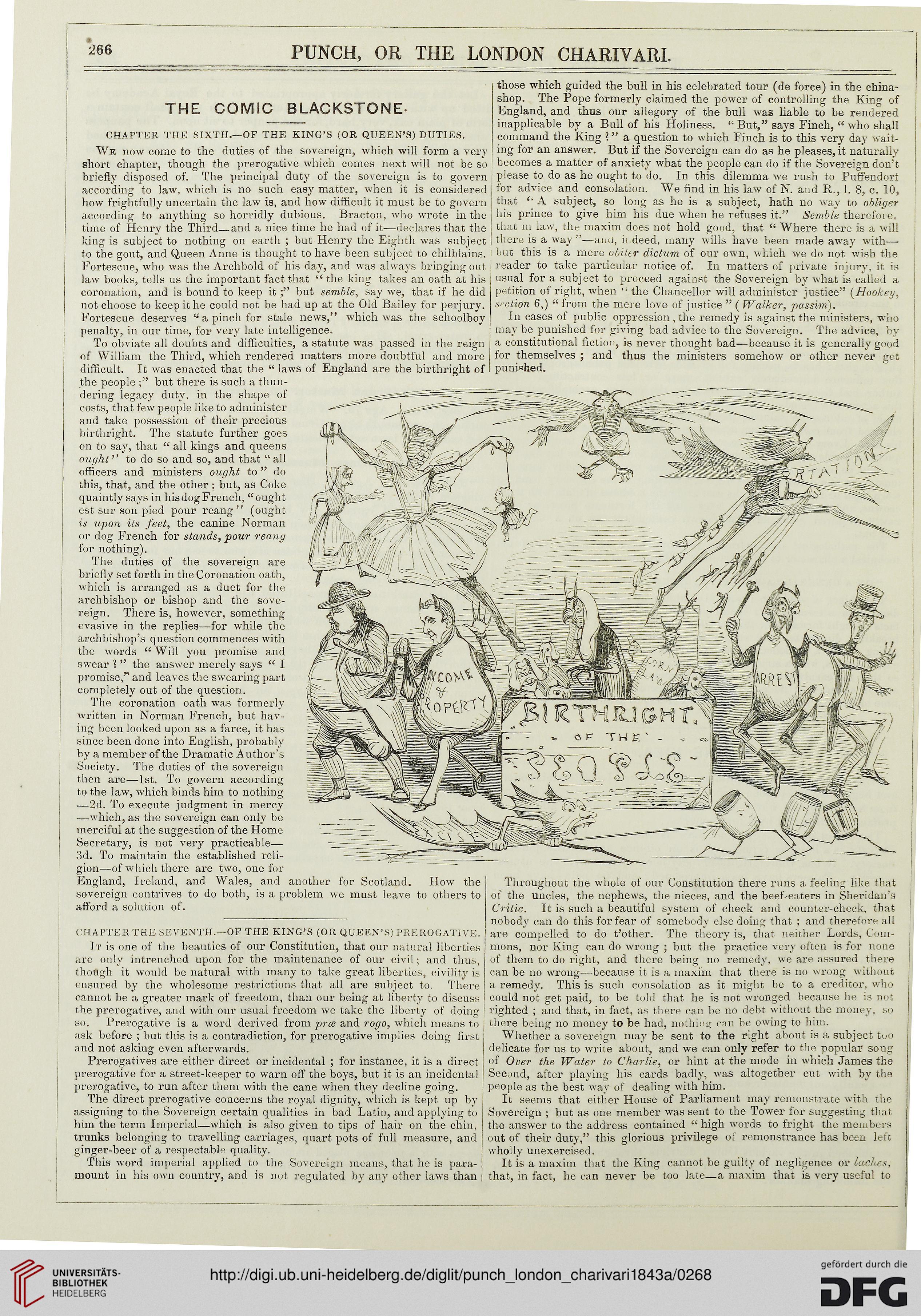

To obviate all doubts and difficulties, a statute was passed in the reign

of William the Third, which rendered matters more doubtful and more

difficult. It was enacted that the " laws of England are the birthright of

the people but there is such a thun-

dering legacy duty, in the shape of

costs, that few people like to administer

and take possession of their precious

birthright. The statute further goes

on to say, that " all kings and queens

ought" to do so and so, and that "all

officers and ministers ought to" do

this, that, and the other : but, as Coke

quaintly says in hisdogFrench, "ought

est sur son pied pour reang " (ought

is upon lis feet, the canine Norman

or dog French for stands, pour reang

for nothing).

The duties of the sovereign are

briefly set forth in the Coronation oath,

which is arranged as a duet for the

archbishop or bishop and the sove-

reign. There is, however, something

evasive in the replies—for while the

archbishop's question commences with

the words " Will you promise and

swear ? " the answer merely says " I

promise,'' and leaves the swearing part

completely out of the question.

The coronation oath was formerly

written in Norman French, but hav-

ing been looked upon as a farce, it has

since been done into English, probably

by a member of the Dramatic A uthor's

Society. The duties of the sovereign

then are—-1st. To govern according

to the law, which binds him to nothing

—2d. To execute judgment in mercy

—which, as the sovereign can only be

merciful at the suggestion of the Home

Secretary, is not very practicable—

3d. To maintain the established reli-

gion—of which there are two, one for

England, Ireland, and Wales, and another for Scotland. How the

sovereign contrives to do both, is a problem we must leave to others to

afford a solution of.

those which guided the bull in his celebrated tour (de force) in the china-

shop. The Pope formerly claimed the power of controlling the King of

England, and thus our allegory of the bull was liable to be rendered

inapplicable by a Bull of his Holiness. " But," says Finch, " who shall

command the King ?" a question to which Finch is to this very day wait-

ing for an answer. But if the Sovereign can do as he pleases, it naturally

becomes a matter of anxiety what the people can do if the Sovereign don't

please to do as he ought to do. In this dilemma we rush to Puffendort

for advice and consolation. We find in his law of N. and R., 1. 8, c. 10,

that '' A subject, so long as he is a subject, hath no way to obliger

his prince to give him his due when he refuses it." Semble therefore,

that m law, the maxim does not hold good, that " Where there is a will

there is a way "—auu, ii.deed, many wills have been made away with—

i but this is a mere obiter dictum of our own, which we do not wish the

reader to take particular notice of. In matters of private injury, it is

usual for a subject to proceed against the Sovereign by what is called a

petition of right, when " the Chancellor will administer justice" (Hookey,

section 6,) " from the mere love of justice " ( Walker, passim).

In cases of public oppression , the remedy is against the ministers, who

may be punished for giving bad advice to the Sovereign. The advice, by

a constitutional fiction, is never thought bad—because it is generally good

for themselves ; and thus the ministers somehow or other never get

punished.

chapter the seventh.—of the king's (or queen's) prerogative.

It is one of the beauties of our Constitution, that our natural liberties

are only intrenched upon for the maintenance of our civil; and thus,

thoflgh it would be natural with many to take great liberties, civility is

ensured by the wholesome restrictions that all are subject to. There

cannot be a greater mark of freedom, than our being at liberty to discuss

the prerogative, and with our usual freedom we take the liberty of doing

so. Prerogative is a word derived from prce and rogo, which means to

ask before ; but this is a contradiction, for prerogative implies doing first

and not asking even afterwards.

Prerogatives are either direct or incidental ; for instance, it is a direct

prerogative for a street-keeper to warn off the boys, but it is an incidental

prerogative, to run after them with the cane when they decline going.

The direct prerogative concerns the royal dignity, which is kept up by

assigning to the Sovereign certain qualities in bad Latin, and applying to

htm the term Imperial—which is also given to tips of hair on the chin,

trunks belonging to travelling carriages, quart pots of full measure, and

ginger-beer of a respectable quality.

This word imperial applied to the Sovereign means, that he is para-

mount in his own country, and is not regulated by any other laws than

Throughout the whole of our Constitution there runs a. feeling like that

of the uncles, the nephews, the nieces, and the beef-eaters in Sheridan's

Critic. It is such a beautiful system of check and counter-check, that

nobody can do this for fear of somebody else doing that ; and therefore all

are compelled to do t'other. The theory is, that neither Lords, Com-

mons, nor King can do wrong ; but the practice very often is for none

of them to do right, and there being no remedy, we are assured there

can be no wrong—because it is a maxim that there is no wrong without

a remedy. This is such consolation as it might be to a creditor, who

could not get paid, to be told that he is not wronged because he is not

righted ; and that, in fact, as there can be no debt without the money, so

there being no money to be had, nothing enn be owing to him.

Whether a sovereign may be sent to the right about is a subject too

delicate for us to write about, and we can only refer to the popular soug

of Over the. Water to Charlie, or hint at the mode in which James the

Second, after playing his cards badly, was altogether cut with by the

people as the best way of dealing with him.

It seems that either House of Parliament may remonstrate with the

Sovereign ; but as one member was sent to the Tower for suggesting that

the answer to the address contained " high words to fright the members

out of their duty," this glorious privilege of remonstrance has been left

wholly unexercised.

It is a maxim that the King cannot be guilty of negligence or laches,

that, in fact, he can never be too late—a maxim that is very useful to

PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

THE COMIC BLACKSTONE-

chapter the sixth.—of the king's (or queen's) duties.

We now come to the duties of the sovereign, which will form a very

short chapter, though the prerogative which comes next will not be so

briefly disposed of. The principal duty of the sovereign is to govern

according to law, which is no such easy matter, when it is considered

how frightfully uncertain the law is, and how difficult it must be to govern

according to anything so horridly dubious. Bracton, who wrote in the

time of Henry the Third—and a nice time he had of it—declares that the

king is subject to nothing on earth ; but Henry the Eighth was subject

to the gout, and Queen Anne is thought to have been subject to chilblains.

Fortescue, who was the Archbold of his day, and was always bringing out

law books, tells us the important fact that " the king takes an oath at his

coronation, and is bound to keep it but semble, say we, that if he did

not choose to keep it he could not be had up at the Old Bailey for perjury.

Fortescue deserves " a pinch for stale news," which was the schoolboy

penalty, in our time, for very late intelligence.

To obviate all doubts and difficulties, a statute was passed in the reign

of William the Third, which rendered matters more doubtful and more

difficult. It was enacted that the " laws of England are the birthright of

the people but there is such a thun-

dering legacy duty, in the shape of

costs, that few people like to administer

and take possession of their precious

birthright. The statute further goes

on to say, that " all kings and queens

ought" to do so and so, and that "all

officers and ministers ought to" do

this, that, and the other : but, as Coke

quaintly says in hisdogFrench, "ought

est sur son pied pour reang " (ought

is upon lis feet, the canine Norman

or dog French for stands, pour reang

for nothing).

The duties of the sovereign are

briefly set forth in the Coronation oath,

which is arranged as a duet for the

archbishop or bishop and the sove-

reign. There is, however, something

evasive in the replies—for while the

archbishop's question commences with

the words " Will you promise and

swear ? " the answer merely says " I

promise,'' and leaves the swearing part

completely out of the question.

The coronation oath was formerly

written in Norman French, but hav-

ing been looked upon as a farce, it has

since been done into English, probably

by a member of the Dramatic A uthor's

Society. The duties of the sovereign

then are—-1st. To govern according

to the law, which binds him to nothing

—2d. To execute judgment in mercy

—which, as the sovereign can only be

merciful at the suggestion of the Home

Secretary, is not very practicable—

3d. To maintain the established reli-

gion—of which there are two, one for

England, Ireland, and Wales, and another for Scotland. How the

sovereign contrives to do both, is a problem we must leave to others to

afford a solution of.

those which guided the bull in his celebrated tour (de force) in the china-

shop. The Pope formerly claimed the power of controlling the King of

England, and thus our allegory of the bull was liable to be rendered

inapplicable by a Bull of his Holiness. " But," says Finch, " who shall

command the King ?" a question to which Finch is to this very day wait-

ing for an answer. But if the Sovereign can do as he pleases, it naturally

becomes a matter of anxiety what the people can do if the Sovereign don't

please to do as he ought to do. In this dilemma we rush to Puffendort

for advice and consolation. We find in his law of N. and R., 1. 8, c. 10,

that '' A subject, so long as he is a subject, hath no way to obliger

his prince to give him his due when he refuses it." Semble therefore,

that m law, the maxim does not hold good, that " Where there is a will

there is a way "—auu, ii.deed, many wills have been made away with—

i but this is a mere obiter dictum of our own, which we do not wish the

reader to take particular notice of. In matters of private injury, it is

usual for a subject to proceed against the Sovereign by what is called a

petition of right, when " the Chancellor will administer justice" (Hookey,

section 6,) " from the mere love of justice " ( Walker, passim).

In cases of public oppression , the remedy is against the ministers, who

may be punished for giving bad advice to the Sovereign. The advice, by

a constitutional fiction, is never thought bad—because it is generally good

for themselves ; and thus the ministers somehow or other never get

punished.

chapter the seventh.—of the king's (or queen's) prerogative.

It is one of the beauties of our Constitution, that our natural liberties

are only intrenched upon for the maintenance of our civil; and thus,

thoflgh it would be natural with many to take great liberties, civility is

ensured by the wholesome restrictions that all are subject to. There

cannot be a greater mark of freedom, than our being at liberty to discuss

the prerogative, and with our usual freedom we take the liberty of doing

so. Prerogative is a word derived from prce and rogo, which means to

ask before ; but this is a contradiction, for prerogative implies doing first

and not asking even afterwards.

Prerogatives are either direct or incidental ; for instance, it is a direct

prerogative for a street-keeper to warn off the boys, but it is an incidental

prerogative, to run after them with the cane when they decline going.

The direct prerogative concerns the royal dignity, which is kept up by

assigning to the Sovereign certain qualities in bad Latin, and applying to

htm the term Imperial—which is also given to tips of hair on the chin,

trunks belonging to travelling carriages, quart pots of full measure, and

ginger-beer of a respectable quality.

This word imperial applied to the Sovereign means, that he is para-

mount in his own country, and is not regulated by any other laws than

Throughout the whole of our Constitution there runs a. feeling like that

of the uncles, the nephews, the nieces, and the beef-eaters in Sheridan's

Critic. It is such a beautiful system of check and counter-check, that

nobody can do this for fear of somebody else doing that ; and therefore all

are compelled to do t'other. The theory is, that neither Lords, Com-

mons, nor King can do wrong ; but the practice very often is for none

of them to do right, and there being no remedy, we are assured there

can be no wrong—because it is a maxim that there is no wrong without

a remedy. This is such consolation as it might be to a creditor, who

could not get paid, to be told that he is not wronged because he is not

righted ; and that, in fact, as there can be no debt without the money, so

there being no money to be had, nothing enn be owing to him.

Whether a sovereign may be sent to the right about is a subject too

delicate for us to write about, and we can only refer to the popular soug

of Over the. Water to Charlie, or hint at the mode in which James the

Second, after playing his cards badly, was altogether cut with by the

people as the best way of dealing with him.

It seems that either House of Parliament may remonstrate with the

Sovereign ; but as one member was sent to the Tower for suggesting that

the answer to the address contained " high words to fright the members

out of their duty," this glorious privilege of remonstrance has been left

wholly unexercised.

It is a maxim that the King cannot be guilty of negligence or laches,

that, in fact, he can never be too late—a maxim that is very useful to

Werk/Gegenstand/Objekt

Titel

Titel/Objekt

Comic of Blackstone

Weitere Titel/Paralleltitel

Serientitel

Punch or The London charivari

Sachbegriff/Objekttyp

Inschrift/Wasserzeichen

Aufbewahrung/Standort

Aufbewahrungsort/Standort (GND)

Inv. Nr./Signatur

H 634-3 Folio

Objektbeschreibung

Objektbeschreibung

Bildbeschriftung: Birthright of the people

Maß-/Formatangaben

Auflage/Druckzustand

Werktitel/Werkverzeichnis

Herstellung/Entstehung

Künstler/Urheber/Hersteller (GND)

Entstehungsdatum

um 1843

Entstehungsdatum (normiert)

1838 - 1848

Entstehungsort (GND)

Auftrag

Publikation

Fund/Ausgrabung

Provenienz

Restaurierung

Sammlung Eingang

Ausstellung

Bearbeitung/Umgestaltung

Thema/Bildinhalt

Thema/Bildinhalt (GND)

Literaturangabe

Rechte am Objekt

Aufnahmen/Reproduktionen

Künstler/Urheber (GND)

Reproduktionstyp

Digitales Bild

Rechtsstatus

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Creditline

Punch or The London charivari, 5.1843, S. 266

Beziehungen

Erschließung

Lizenz

CC0 1.0 Public Domain Dedication

Rechteinhaber

Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg