APPENDIX C. MINOAN WRITING AND DRESS

ASIDE from their value in the history of Aegean writing, the pictographic and pictorial seal- f ■ ^1

stones reflect also the civilization of the times.1 On them we see the domestic animals of the

Minoans, the horse,2 the bull, the goat, the pig; we find the Minoans sailing the sea, hunting

L the lion, the deer, the wild goat; we witness their athletic contests and the fierce encounters A.

HE unfortunate destruction of frescoes at Gournia has deprived us of possible pictures of

Minoan men and women, which form some of the most'instructive remains at Knossos and

Aghia Triadha for our knowledge of Minoan dress. But we have other finds that may serve

the lion, the deer, the wild goat; we witness their athletic contests and the fierce encounters J. as fashion plates, when supplemented by illustrations from elsewhere. The dress of our

of wild beasts; the flowers they loved and their ornamental designs delight us; we look with amazement bronze statuette of a man (PI. XI 21) consists probably of the Aegean clout alone, although the

and uncomprehending eyes upon the monsters they depicted; and we exercise our ingenuity in trying to corrosion of the surface makes it doubtful whether he may not have worn either drawers like those of

explain their beasts in heraldic postures, the dancing men and women, the attitudes of adoration, and the bull-tamers on the Vaphio cups,10 and the lion-hunters on a dagger from My-

other scenes of Minoan cult so frequently represented on gems and gold bezels of rings. Such a culture MINOAN DRESS cenae," or a loincloth in the fashion of the cup-bearer on the Knossian fresco.12

betokens no ordinary race, but a people fired by imagination and driven by genius to express it. Our figure is the best example yet found of the way in which men of the Minoan race

Side by side with the hieroglyphic script (p. 54) and, like it, probably derived from picto- wore their hair, in three twists on the head, and three long braids or curls falling over neck and shoulders,

grams, a linear form of writing—Dr. Evans's Class A3—was employed very generally by the Though this statuette shows no sign of footgear, we know from other sources that buskins and puttees

Minoans in the First Late Minoan Period. In the following era, Class B of were frequently worn.13 An important part of the costume was a thick belt by which the slender

LINEAR SCRIPT the Linear Script appears at Knossos and is found on the clay tablets com- waists of the men were emphasized, and into which were thrust such daggers as are seen on Plate IV.14

prising the immense archives of the Palace Period. This seems to be not a The little electron figurine (PI. XI 14), no doubt reproduces the dress of the lady for whose

derivative from Class A, but a parallel form, and in the opinion of Dr. Evans its presence is due to a adornment it was made. On all Minoan sites have been met large and small representations of women

dynastic change. These Palace records appear to be mostly accounts and inventories, and a decimal attired in similar bell-shaped skirts, the style of which is varied by

system similar to the Egyptian has been deciphered in which the units are s-~^~-<^s>^~ /fl»w$k plaited ruffles and straight bands (Fig. 28, 8),15 or by diagonal flounces

represented by upright lines, the tens by horizontal, the hundreds by circles, if/ N> ./^t^ NjjjlP anc* bands (Fig. 28, 7), while often the skirt is flounced from top to bot-

and the thousands by circles with four spurs. As is shown by tablets from KL I _ >*f|_fr torn with ruffles of varying widths and colors.16 Unfortunately, there

the House of the Fetish Shrine, this class of writing was still employed when the

day of destruction fell upon the remnant of the Minoans who had established

themselves amid the ruins of Knossos in the Third Late Minoan Period.

Moreover, we may believe that although letters died in Crete they did not

perish utterly with the Minoan civilization, but passed from the Cretans to

other nations, possibly through the Phoenicians, even as Diodorus relates.4

In addition to these forms of writing, there are marks on masonry, pot-

tery, and the reverse side of ivory, bone, and porcelain inlays. These last

are analogous to the Egyptian signary, and, though of pictorial origin, they

were early reduced to a simple script and appear alphabetic. Of twenty-one

varieties on the back of inlays found at Knossos ten marks "are practically

identical with forms of the later Greek alphabet."6 The marks on masonry

occur chiefly at Knossos and Phaestos and consist of the double-axe, trident,

9

are no representations of women from Gournia sufficiently large to illus-

trate the Minoan style of bodice, but frescoes and the faience statuettes

from Knossos exhibit an elaborate, tightly fitting bodice, laced in front

into a small waist, with short sleeves, sometimes puffed, and a very low

open neck. The appearance is strikingly like that of a modern peasant

bodice worn without a chemisette.17 As in the case of the men, the

waist is confined by a broad belt. A glance at the shrine fresco from

Knossos reveals surprisingly modern styles of hair dressing. Long,

waving tresses, twists and coquettish little curls that might be the work

of a Parisian "coiffeur de dames," were affected by the beauties of

the Knossos court.18 It is evident that such elaborate coiffures must

have been held in place by strong pins, and although a modern woman

would be at a loss to know how to use a hairpin like Fig. 35, 7," we

tree and about twenty-five other signs more or less definite, for some of which a ^-^J.^^^ m'w'$J™ must suppose that a Minoan lady found such pins entirely adequate for

religious significance is claimed. In the writer's eyes, however, such signs as ^^"^ nMkjw ^er PurPoses- Eight examples from Gournia were of this type, while

the double-axe and the trident have a meaning primarily associated with a fam- . ^ ^H^p^ onjy one was shaped like the more convenient modern article,

ily, clan, or class,11 whence various usages might arise in accordance with which fig. 35 Jewelry was worn by both men and women. The

masons would carve either their own mark on the stone, or the mark of the person for whom the cup-bearer of Knossos has a seal- stone on a thin

stone was cut. We have only one sign of this kind at Gournia, a double-axe (Fig. 9, p. 25), scratched bracelet at his wrist, and a broad band on his upper arm; the Jlillr\ "Dove Goddess"

on the outer face of a block of ashlar masonry on the south side of G 13. Such careless, superficial of Knossos is similarly adorned. Our beads (Fig. 35, 1, 2, 4, 6) \l|P^ ^\ are Parts °f neck-

cutting suggests that it was done somewhat wantonly, to mark the palace of the local governor as laces, which appear to have been ornaments for both sexes. TO -f No complete neck-

the House of the Double-axe. laces were discovered at Gournia, but from the finds of such M$ \~ single beads of

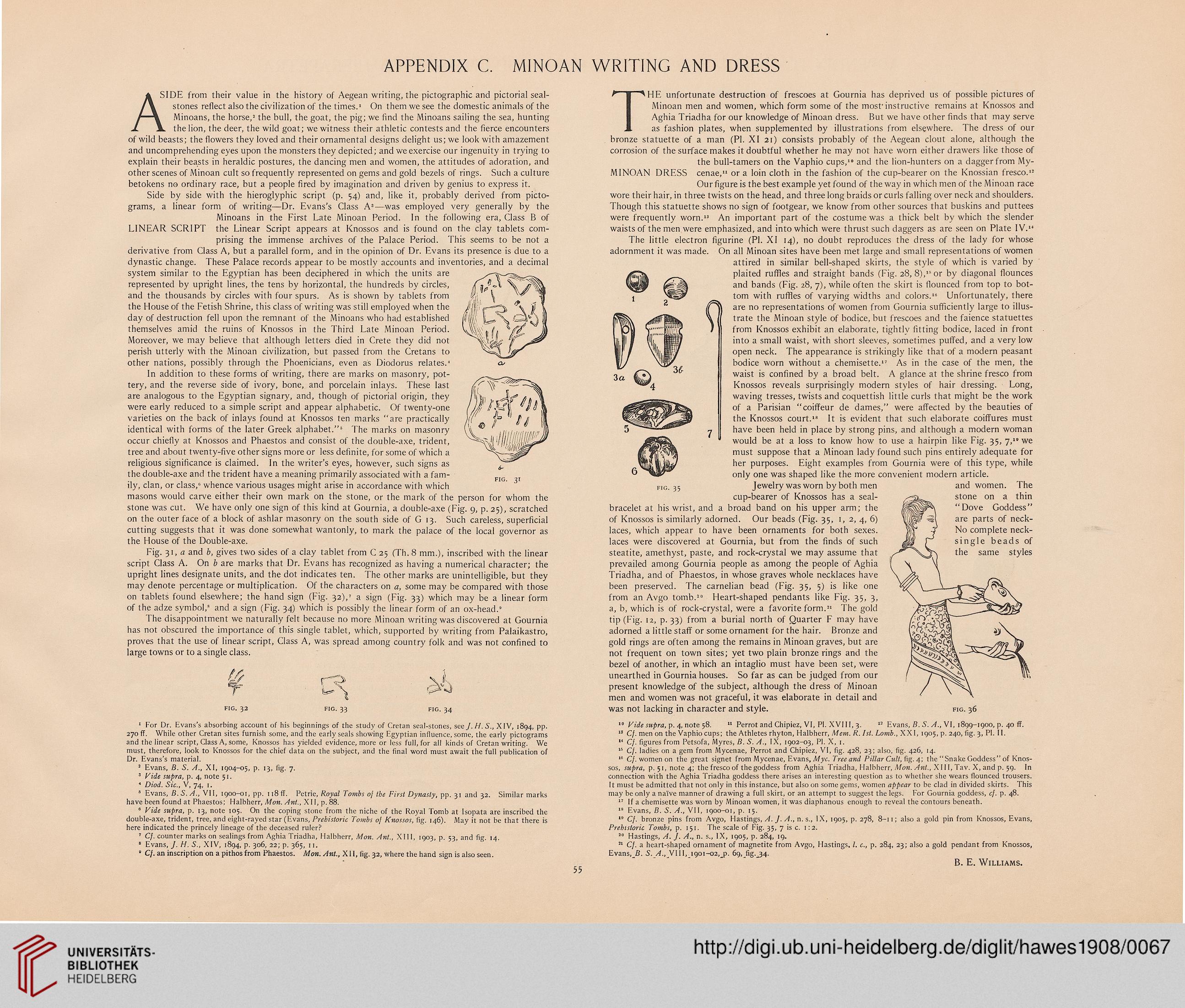

Fig. 31, a and b, gives two sides of a clay tablet from C 25 (Th.8 mm.), inscribed with the linear steatite, amethyst, paste, and rock-crystal we may assume that ,/^^\^) t^le same styles

script Class A. On b are marks that Dr. Evans has recognized as having a numerical character; the prevailed among Gournia people as among the people of Aghia

upright lines designate units, and the dot indicates ten. The other marks are unintelligible, but they Triadha, and of Phaestos, in whose graves whole necklaces have

may denote percentage or multiplication. Of the characters on a, some may be compared with those been preserved. The carnelian bead (Fig. 35, 5) is like one

on tablets found elsewhere; the hand sign (Fig. 32)/ a sign (Fig. 33) which may be a linear form from an Avgo tomb.20 Heart-shaped pendants like Fig. 35, 3,

of the adze symbol," and a sign (Fig. 34) which is possibly the linear form of an ox-head." a, b, which is of rock-crystal, were a favorite form.21 The gold

The disappointment we naturally felt because no more Minoan writing was discovered at Gournia tip (Fig. 12, p. 33) from a burial north of Quarter F may have

has not obscured the importance of this single tablet, which, supported by writing from Palaikastro, adorned a little staff or some ornament for the hair. Bronze and

proves that the use of linear script, Class A, was spread among country folk and was not confined to gold rings are often among the remains in Minoan graves, but are

large towns or to a single class. not frequent on town sites; yet two plain bronze rings and the

bezel of another, in which an intaglio must have been set, were

. j| unearthed in Gournia houses. So far as can be judged from our

j^-'X ! J^O) present knowledge of the subject, although the dress of Minoan

men and women was not graceful, it was elaborate in detail and

fig. 32 fig. 33 fig. 34 was not lacking in character and style. fig. 36

1 For Dr. Evans's absorbing account of his beginnings of the study of Cretan seal-stones, see /. H. S., XIV, 1894, pp. 10 Vide supra, p. 4, note 58. 11 Perrot and Chipiez, VI, PI. XVIII, 3. 12 Evans, B. S. A., VI, 1899-1900, p. 40 ff.

270 ff. While other Cretan sites furnish some, and the early seals showing Egyptian influence, some, the early pictograms " Q- men on the Vaphio cups; the Athletes rhyton, Halbherr, Mem. R. 1st. Lomb., XXI, 1905, p. 240, fig. 3, PI. II.

and the linear script, Class A, some, Knossos has yielded evidence, more or less full, for all kinds of Cretan writing. We 14 Q- figures from Petsofa, Myres, B. S. A., IX, 1902-03, PI. X, 1.

must, therefore, look to Knossos for the chief data on the subject, and the final word must await the full publication of u Cj. ladies on a gem from Mycenae, Perrot and Chipiez, VI, fig. 428, 23; also, fig. 426, 14.

Dr. Evans's material. 10 Cj. women on the great signet from Mycenae, Evans, Myc. Tree and Pillar Cull, fig. 4; the "Snake Goddess" of Knos-

2 Evans, B. S. A., XI, 1904-05, p. 13, fig. 7. sos, supra, p. 51, note 4; the fresco of the goddess from Aghia Triadha, Halbherr, Mon. Ant, XIII, Tav. X, and p. 59. In

3 Vide supra, p. 4, note 51. connection with the Aghia Triadha goddess there arises an interesting question as to whether she wears flounced trousers.

4 Diod. Sic, V, 74, 1. It must be admitted that not only in this instance, but also on some gems, women appear to be clad in divided skirts. This

* Evans, B. S. A., VII, 1900-01, pp. n8ff. Petrie, Royal Tombs oj the First Dynasty, pp. 31 and 32. Similar marks may be only a naive manner of drawing a full skirt, or an attempt to suggest the legs. For Gournia goddess, cf. p. 48.

have been found at Phaestos; Halbherr, Mon. Ant., XII, p. 88. 17 If a chemisette was worn by Minoan women, it was diaphanous enough to reveal the contours beneath.

6 Vide supra, p. 13, note 105. On the coping stone from the niche of the Royal Tomb at Isopata are inscribed the 18 Evans, B. S. A., VII, 1900-01, p. 15.

double-axe, trident, tree, and eight-rayed star (Evans, Prehistoric Tombs of Knossos, fig. 146). May it not be that there is 19 Cj. bronze pins from Avgo, Hastings, A. J. A., n. s., IX, 1905, p. 278, 8-11; also a gold pin from Knossos, Evans,

here indicated the princely lineage of the deceased ruler? Prehistoric Tombs, p. 151. The scale of Fig. 35, 7 is c. 1:2.

* Cj. counter marks on sealings from Aghia Triadha, Halbherr, Mon. Ant., XIII, 1903, p. 53, and fig. 14. 20 Hastings, A. J. A., n. s., IX, 1905, p. 284, 19.

* Evans, J. H. S., XIV, 1894, p. 306, 22; p. 365, 11. 21 Cf. a heart-shaped ornament of magnetite from Avgo, Hastings. /. c, p. 284, 23; also a gold pendant from Knossos,

" Cj. an inscription on a pithosfrom Phaestos. Mon. Ant., XII, fig. 32, where the hand sign is also seen. Evans,_fl. S. A., VIII, 1901-02,j>. 69._fig.34.

B. E. Williams.

55

ASIDE from their value in the history of Aegean writing, the pictographic and pictorial seal- f ■ ^1

stones reflect also the civilization of the times.1 On them we see the domestic animals of the

Minoans, the horse,2 the bull, the goat, the pig; we find the Minoans sailing the sea, hunting

L the lion, the deer, the wild goat; we witness their athletic contests and the fierce encounters A.

HE unfortunate destruction of frescoes at Gournia has deprived us of possible pictures of

Minoan men and women, which form some of the most'instructive remains at Knossos and

Aghia Triadha for our knowledge of Minoan dress. But we have other finds that may serve

the lion, the deer, the wild goat; we witness their athletic contests and the fierce encounters J. as fashion plates, when supplemented by illustrations from elsewhere. The dress of our

of wild beasts; the flowers they loved and their ornamental designs delight us; we look with amazement bronze statuette of a man (PI. XI 21) consists probably of the Aegean clout alone, although the

and uncomprehending eyes upon the monsters they depicted; and we exercise our ingenuity in trying to corrosion of the surface makes it doubtful whether he may not have worn either drawers like those of

explain their beasts in heraldic postures, the dancing men and women, the attitudes of adoration, and the bull-tamers on the Vaphio cups,10 and the lion-hunters on a dagger from My-

other scenes of Minoan cult so frequently represented on gems and gold bezels of rings. Such a culture MINOAN DRESS cenae," or a loincloth in the fashion of the cup-bearer on the Knossian fresco.12

betokens no ordinary race, but a people fired by imagination and driven by genius to express it. Our figure is the best example yet found of the way in which men of the Minoan race

Side by side with the hieroglyphic script (p. 54) and, like it, probably derived from picto- wore their hair, in three twists on the head, and three long braids or curls falling over neck and shoulders,

grams, a linear form of writing—Dr. Evans's Class A3—was employed very generally by the Though this statuette shows no sign of footgear, we know from other sources that buskins and puttees

Minoans in the First Late Minoan Period. In the following era, Class B of were frequently worn.13 An important part of the costume was a thick belt by which the slender

LINEAR SCRIPT the Linear Script appears at Knossos and is found on the clay tablets com- waists of the men were emphasized, and into which were thrust such daggers as are seen on Plate IV.14

prising the immense archives of the Palace Period. This seems to be not a The little electron figurine (PI. XI 14), no doubt reproduces the dress of the lady for whose

derivative from Class A, but a parallel form, and in the opinion of Dr. Evans its presence is due to a adornment it was made. On all Minoan sites have been met large and small representations of women

dynastic change. These Palace records appear to be mostly accounts and inventories, and a decimal attired in similar bell-shaped skirts, the style of which is varied by

system similar to the Egyptian has been deciphered in which the units are s-~^~-<^s>^~ /fl»w$k plaited ruffles and straight bands (Fig. 28, 8),15 or by diagonal flounces

represented by upright lines, the tens by horizontal, the hundreds by circles, if/ N> ./^t^ NjjjlP anc* bands (Fig. 28, 7), while often the skirt is flounced from top to bot-

and the thousands by circles with four spurs. As is shown by tablets from KL I _ >*f|_fr torn with ruffles of varying widths and colors.16 Unfortunately, there

the House of the Fetish Shrine, this class of writing was still employed when the

day of destruction fell upon the remnant of the Minoans who had established

themselves amid the ruins of Knossos in the Third Late Minoan Period.

Moreover, we may believe that although letters died in Crete they did not

perish utterly with the Minoan civilization, but passed from the Cretans to

other nations, possibly through the Phoenicians, even as Diodorus relates.4

In addition to these forms of writing, there are marks on masonry, pot-

tery, and the reverse side of ivory, bone, and porcelain inlays. These last

are analogous to the Egyptian signary, and, though of pictorial origin, they

were early reduced to a simple script and appear alphabetic. Of twenty-one

varieties on the back of inlays found at Knossos ten marks "are practically

identical with forms of the later Greek alphabet."6 The marks on masonry

occur chiefly at Knossos and Phaestos and consist of the double-axe, trident,

9

are no representations of women from Gournia sufficiently large to illus-

trate the Minoan style of bodice, but frescoes and the faience statuettes

from Knossos exhibit an elaborate, tightly fitting bodice, laced in front

into a small waist, with short sleeves, sometimes puffed, and a very low

open neck. The appearance is strikingly like that of a modern peasant

bodice worn without a chemisette.17 As in the case of the men, the

waist is confined by a broad belt. A glance at the shrine fresco from

Knossos reveals surprisingly modern styles of hair dressing. Long,

waving tresses, twists and coquettish little curls that might be the work

of a Parisian "coiffeur de dames," were affected by the beauties of

the Knossos court.18 It is evident that such elaborate coiffures must

have been held in place by strong pins, and although a modern woman

would be at a loss to know how to use a hairpin like Fig. 35, 7," we

tree and about twenty-five other signs more or less definite, for some of which a ^-^J.^^^ m'w'$J™ must suppose that a Minoan lady found such pins entirely adequate for

religious significance is claimed. In the writer's eyes, however, such signs as ^^"^ nMkjw ^er PurPoses- Eight examples from Gournia were of this type, while

the double-axe and the trident have a meaning primarily associated with a fam- . ^ ^H^p^ onjy one was shaped like the more convenient modern article,

ily, clan, or class,11 whence various usages might arise in accordance with which fig. 35 Jewelry was worn by both men and women. The

masons would carve either their own mark on the stone, or the mark of the person for whom the cup-bearer of Knossos has a seal- stone on a thin

stone was cut. We have only one sign of this kind at Gournia, a double-axe (Fig. 9, p. 25), scratched bracelet at his wrist, and a broad band on his upper arm; the Jlillr\ "Dove Goddess"

on the outer face of a block of ashlar masonry on the south side of G 13. Such careless, superficial of Knossos is similarly adorned. Our beads (Fig. 35, 1, 2, 4, 6) \l|P^ ^\ are Parts °f neck-

cutting suggests that it was done somewhat wantonly, to mark the palace of the local governor as laces, which appear to have been ornaments for both sexes. TO -f No complete neck-

the House of the Double-axe. laces were discovered at Gournia, but from the finds of such M$ \~ single beads of

Fig. 31, a and b, gives two sides of a clay tablet from C 25 (Th.8 mm.), inscribed with the linear steatite, amethyst, paste, and rock-crystal we may assume that ,/^^\^) t^le same styles

script Class A. On b are marks that Dr. Evans has recognized as having a numerical character; the prevailed among Gournia people as among the people of Aghia

upright lines designate units, and the dot indicates ten. The other marks are unintelligible, but they Triadha, and of Phaestos, in whose graves whole necklaces have

may denote percentage or multiplication. Of the characters on a, some may be compared with those been preserved. The carnelian bead (Fig. 35, 5) is like one

on tablets found elsewhere; the hand sign (Fig. 32)/ a sign (Fig. 33) which may be a linear form from an Avgo tomb.20 Heart-shaped pendants like Fig. 35, 3,

of the adze symbol," and a sign (Fig. 34) which is possibly the linear form of an ox-head." a, b, which is of rock-crystal, were a favorite form.21 The gold

The disappointment we naturally felt because no more Minoan writing was discovered at Gournia tip (Fig. 12, p. 33) from a burial north of Quarter F may have

has not obscured the importance of this single tablet, which, supported by writing from Palaikastro, adorned a little staff or some ornament for the hair. Bronze and

proves that the use of linear script, Class A, was spread among country folk and was not confined to gold rings are often among the remains in Minoan graves, but are

large towns or to a single class. not frequent on town sites; yet two plain bronze rings and the

bezel of another, in which an intaglio must have been set, were

. j| unearthed in Gournia houses. So far as can be judged from our

j^-'X ! J^O) present knowledge of the subject, although the dress of Minoan

men and women was not graceful, it was elaborate in detail and

fig. 32 fig. 33 fig. 34 was not lacking in character and style. fig. 36

1 For Dr. Evans's absorbing account of his beginnings of the study of Cretan seal-stones, see /. H. S., XIV, 1894, pp. 10 Vide supra, p. 4, note 58. 11 Perrot and Chipiez, VI, PI. XVIII, 3. 12 Evans, B. S. A., VI, 1899-1900, p. 40 ff.

270 ff. While other Cretan sites furnish some, and the early seals showing Egyptian influence, some, the early pictograms " Q- men on the Vaphio cups; the Athletes rhyton, Halbherr, Mem. R. 1st. Lomb., XXI, 1905, p. 240, fig. 3, PI. II.

and the linear script, Class A, some, Knossos has yielded evidence, more or less full, for all kinds of Cretan writing. We 14 Q- figures from Petsofa, Myres, B. S. A., IX, 1902-03, PI. X, 1.

must, therefore, look to Knossos for the chief data on the subject, and the final word must await the full publication of u Cj. ladies on a gem from Mycenae, Perrot and Chipiez, VI, fig. 428, 23; also, fig. 426, 14.

Dr. Evans's material. 10 Cj. women on the great signet from Mycenae, Evans, Myc. Tree and Pillar Cull, fig. 4; the "Snake Goddess" of Knos-

2 Evans, B. S. A., XI, 1904-05, p. 13, fig. 7. sos, supra, p. 51, note 4; the fresco of the goddess from Aghia Triadha, Halbherr, Mon. Ant, XIII, Tav. X, and p. 59. In

3 Vide supra, p. 4, note 51. connection with the Aghia Triadha goddess there arises an interesting question as to whether she wears flounced trousers.

4 Diod. Sic, V, 74, 1. It must be admitted that not only in this instance, but also on some gems, women appear to be clad in divided skirts. This

* Evans, B. S. A., VII, 1900-01, pp. n8ff. Petrie, Royal Tombs oj the First Dynasty, pp. 31 and 32. Similar marks may be only a naive manner of drawing a full skirt, or an attempt to suggest the legs. For Gournia goddess, cf. p. 48.

have been found at Phaestos; Halbherr, Mon. Ant., XII, p. 88. 17 If a chemisette was worn by Minoan women, it was diaphanous enough to reveal the contours beneath.

6 Vide supra, p. 13, note 105. On the coping stone from the niche of the Royal Tomb at Isopata are inscribed the 18 Evans, B. S. A., VII, 1900-01, p. 15.

double-axe, trident, tree, and eight-rayed star (Evans, Prehistoric Tombs of Knossos, fig. 146). May it not be that there is 19 Cj. bronze pins from Avgo, Hastings, A. J. A., n. s., IX, 1905, p. 278, 8-11; also a gold pin from Knossos, Evans,

here indicated the princely lineage of the deceased ruler? Prehistoric Tombs, p. 151. The scale of Fig. 35, 7 is c. 1:2.

* Cj. counter marks on sealings from Aghia Triadha, Halbherr, Mon. Ant., XIII, 1903, p. 53, and fig. 14. 20 Hastings, A. J. A., n. s., IX, 1905, p. 284, 19.

* Evans, J. H. S., XIV, 1894, p. 306, 22; p. 365, 11. 21 Cf. a heart-shaped ornament of magnetite from Avgo, Hastings. /. c, p. 284, 23; also a gold pendant from Knossos,

" Cj. an inscription on a pithosfrom Phaestos. Mon. Ant., XII, fig. 32, where the hand sign is also seen. Evans,_fl. S. A., VIII, 1901-02,j>. 69._fig.34.

B. E. Williams.

55