DESCRIPTION OF MS.

A MS. OF THE SEVENTH CENTURY, KNOWN AS THE "DURHAM BOOK."

PRESERVED W THE COTTONIAN LIBRARY IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

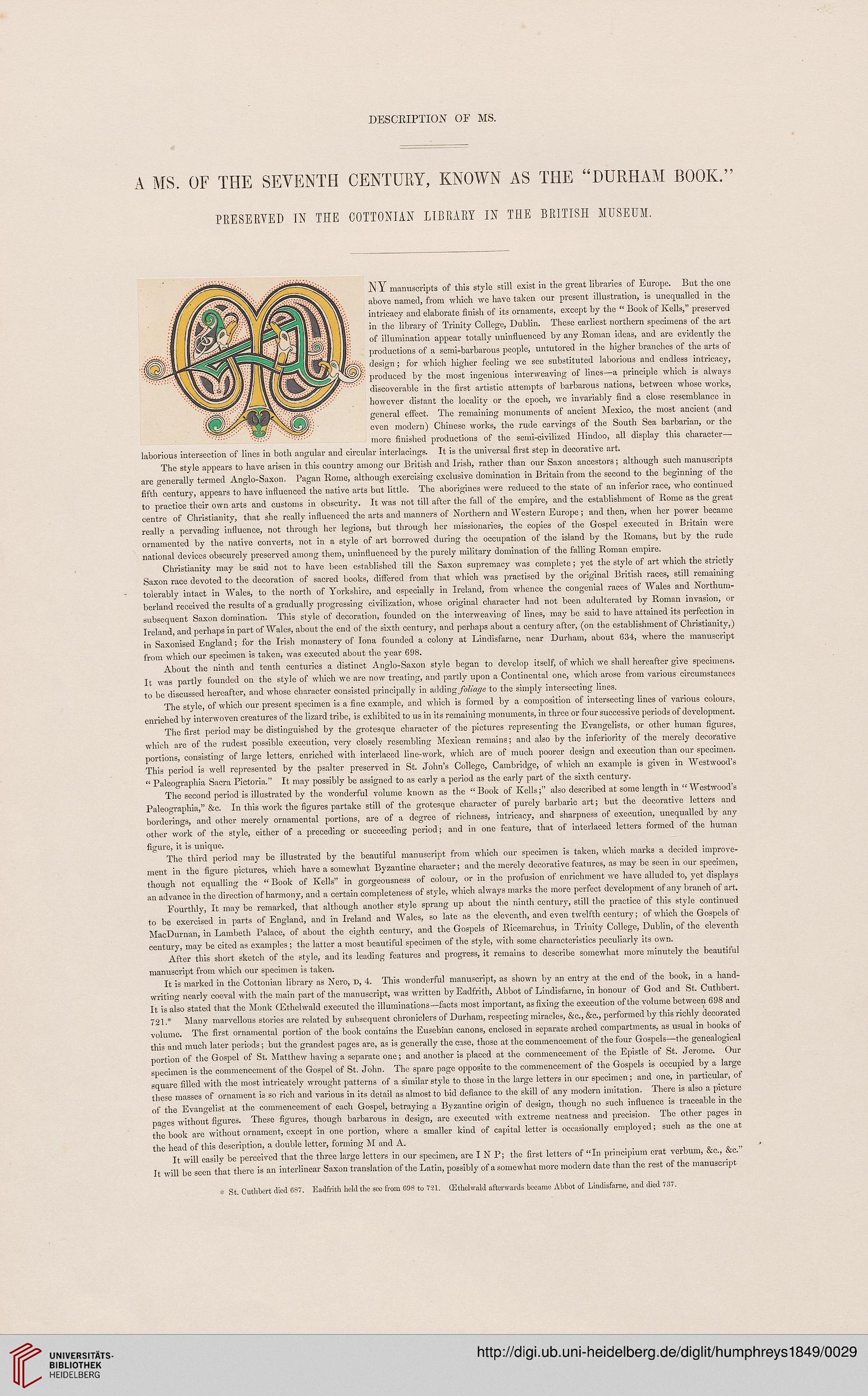

NY manuscripts of this style still exist in the great libraries of Europe. But the one

above named, from which we have taken our present illustration, is unequalled in the

intricacy and elaborate finish of its ornaments, except by the " Book of Kells," preserved

in the library of Trinity College, Dublin. These earliest northern specimens of the art

of illumination appear totally uninfluenced by any Roman ideas, and are evidently the

productions of a semi-barbarous people, untutored in the higher branches of the arts of

design; for which higher feeling we see substituted laborious and endless intricacy,

produced by the most ingenious interweaving of lines—a principle which is always

discoverable in the first artistic attempts of barbarous nations, between whose works,

however distant the locality or the epoch, we invariably find a close resemblance in

general effect. The remaining monuments of ancient Mexico, the most ancient (and

even modern) Chinese works, the rude carvings of the South Sea barbarian, or the

more finished productions of the semi-civilized Hindoo, all display this character-

laborious intersection of lines in both angular and circular interlacings. It is the universal first step in decorative art.

The style appears to have arisen in this country among our British and Irish, rather than our Saxon ancestors; although such manuscripts

are generally termed Anglo-Saxon. Pagan Rome, although exercising exclusive domination in Britain from the second to the beginning of the

fifth century, appears to have influenced the native arts but little. The aborigines were reduced to the state of an inferior race, who continued

to practice their own arts and customs in obscurity. It was not till after the fall of the empire, and the establishment of Rome as the great

centre of Christianity, that she really influenced the arts and manners of Northern and Western Europe; and then, when her power became

really a pervading influence, not through her legions, but through her missionaries, the copies of the Gospel executed in Britain were

ornamented by the native converts, not in a style of art borrowed during the occupation of the island by the Romans, but by the rude

national devices obscurely preserved among them, uninfluenced by the purely military domination of the falling Roman empire.

Christianity may be said not to have been established till the Saxon supremacy was complete; yet the style of art which the strictly

Saxon race devoted to the decoration of sacred books, differed from that which was practised by the original British races, still remaining

tolerably intact in Wales, to the north of Yorkshire, and especially in Ireland, from whence the congenial races of Wales and Northum-

berland received the results of a gradually progressing civilization, whose original character had not been adulterated by Roman invasion, or

subsequent Saxon domination. This style of decoration, founded on the interweaving of lines, may be said to have attained its perfection in

Ireland, and perhaps in part of Wales, about the end of the sixth century, and perhaps about a century after, (on the establishment of Christianity,)

in Saxonised England; for the Irish monastery of Iona founded a colony at Lindisfarne, near Durham, about 634, where the manuscript

from which our specimen is taken, was executed about the year 698.

About the ninth and tenth centuries a distinct Anglo-Saxon style began to develop itself, of which we shall hereafter give specimens.

It was partly founded on the style of which we are now treating, and partly upon a Continental one, which arose from various circumstances

to be discussed hereafter, and whose character consisted principally in adding foliage to the simply intersecting lines.

The style, of which our present specimen is a fine example, and which is formed by a composition of intersecting lines of various colours,

enriched by interwoven creatures of the lizard tribe, is exhibited to us in its remaining monuments, in three or four successive periods of development.

The first period may be distinguished by the grotesque character of the pictures representing the Evangelists, or other human figures,

which are of the rudest possible execution, very closely resembling Mexican remains; and also by the inferiority of the merely decorative

portions, consisting of large letters, enriched with interlaced line-work, which are of much poorer design and execution than our specimen.

This period is well represented by the psalter preserved in St. John's College, Cambridge, of which an example is given in Westwood's

" Paleographia Sacra Pictoria." It may possibly be assigned to as early a period as the early part of the sixth century.

The second period is illustrated by the wonderful volume known as the "Book of Kells;" also described at some length in "Westwood's

Paleographia," &c. In this work the figures partake still of the grotesque character of purely barbaric art; but the decorative letters and

borderings, and other merely ornamental portions, are of a degree of richness, intricacy, and sharpness of execution, unequalled by any

other work of the style, either of a preceding or succeeding period; and in one feature, that of interlaced letters formed of the human

figure, it is unique.

The third period may be illustrated by the beautiful manuscript from which our specimen is taken, which marks a decided improve-

ment in the figure pictures, which have a somewhat Byzantine character; and the merely decorative features, as may be seen in our specimen,

though not equalling the " Book of Kells" in gorgeousness of colour, or in the profusion of enrichment we have alluded to, yet displays

an advance in the direction of harmony, and a certain completeness of style, which always marks the more perfect development of any branch of art.

Fourthly, It may be remarked, that although another style sprang up about the ninth century, still the practice of this style continued

to be exercised in parts of England, and in Ireland and Wales, so late as the eleventh, and even twelfth century; of which the Gospels of

MacDurnan, in Lambeth Palace, of about the eighth century, and the Gospels of Ricemarchus, in Trinity College, Dublin, of the eleventh

century, may be cited as examples; the latter a most beautiful specimen of the style, with some characteristics peculiarly its own.

After this short sketch of the style, and its leading features and progress, it remains to describe somewhat more minutely the beautiful

manuscript from which our specimen is taken.

It is marked in the Cottonian library as Nero, D, 4. This wonderful manuscript, as shown by an entry at the end of the book, in a hand-

writing nearly coeval with the main part of the manuscript, was written by Eadfrith, Abbot of Lindisfarne, in honour of God and St. Cuthbert.

It is also stated that the Monk Githelwald executed the illuminations—facts most important, as fixing the execution of the volume between 698 and

721.*' Many marvellous stories are related by subsequent chroniclers of Durham, respecting miracles, &c, &c, performed by this richly decorated

volume. The first ornamental portion of the book contains the Eusebian canons, enclosed in separate arched compartments, as usual in books of

this and much later periods; but the grandest pages are, as is generally the case, those at the commencement of the four Gospels—the genealogical

portion of the Gospel of St. Matthew having a separate one; and another is placed at the commencement of the Epistle of St. Jerome. Our

specimen is the commencement of the Gospel of St. John. The spare page opposite to the commencement of the Gospels is occupied by a large

square filled with the most intricately wrought patterns of a similar style to those in the large letters in our specimen; and one, in particular, of

these masses of ornament is so rich and various in its detail as almost to bid defiance to the skill of any modern imitation. There is also a picture

of the Evangelist at the commencement of each Gospel, betraying a Byzantine origin of design, though no such influence is traceable in the

pages without figures. These figures, though barbarous in design, are executed with extreme neatness and precision. The other pages in

the book are without ornament, except in one portion, where a smaller kind of capital letter is occasionally employed; such as the one at

the head of this description, a double letter, forming M and A.

It will easily be perceived that the three large letters in our specimen, are I N P; the first letters of "In principium erat verbum, &c, &c."

It will be seen that there is an interlinear Saxon translation of the Latin, possibly of a somewhat more modern date than the rest of the manuscript

* St. Cuthbert died 087. Eadfrith held the see from 698 to 721. (Ethelwald afterwards became Abbot of Lindisfarne, and died 737.

A MS. OF THE SEVENTH CENTURY, KNOWN AS THE "DURHAM BOOK."

PRESERVED W THE COTTONIAN LIBRARY IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

NY manuscripts of this style still exist in the great libraries of Europe. But the one

above named, from which we have taken our present illustration, is unequalled in the

intricacy and elaborate finish of its ornaments, except by the " Book of Kells," preserved

in the library of Trinity College, Dublin. These earliest northern specimens of the art

of illumination appear totally uninfluenced by any Roman ideas, and are evidently the

productions of a semi-barbarous people, untutored in the higher branches of the arts of

design; for which higher feeling we see substituted laborious and endless intricacy,

produced by the most ingenious interweaving of lines—a principle which is always

discoverable in the first artistic attempts of barbarous nations, between whose works,

however distant the locality or the epoch, we invariably find a close resemblance in

general effect. The remaining monuments of ancient Mexico, the most ancient (and

even modern) Chinese works, the rude carvings of the South Sea barbarian, or the

more finished productions of the semi-civilized Hindoo, all display this character-

laborious intersection of lines in both angular and circular interlacings. It is the universal first step in decorative art.

The style appears to have arisen in this country among our British and Irish, rather than our Saxon ancestors; although such manuscripts

are generally termed Anglo-Saxon. Pagan Rome, although exercising exclusive domination in Britain from the second to the beginning of the

fifth century, appears to have influenced the native arts but little. The aborigines were reduced to the state of an inferior race, who continued

to practice their own arts and customs in obscurity. It was not till after the fall of the empire, and the establishment of Rome as the great

centre of Christianity, that she really influenced the arts and manners of Northern and Western Europe; and then, when her power became

really a pervading influence, not through her legions, but through her missionaries, the copies of the Gospel executed in Britain were

ornamented by the native converts, not in a style of art borrowed during the occupation of the island by the Romans, but by the rude

national devices obscurely preserved among them, uninfluenced by the purely military domination of the falling Roman empire.

Christianity may be said not to have been established till the Saxon supremacy was complete; yet the style of art which the strictly

Saxon race devoted to the decoration of sacred books, differed from that which was practised by the original British races, still remaining

tolerably intact in Wales, to the north of Yorkshire, and especially in Ireland, from whence the congenial races of Wales and Northum-

berland received the results of a gradually progressing civilization, whose original character had not been adulterated by Roman invasion, or

subsequent Saxon domination. This style of decoration, founded on the interweaving of lines, may be said to have attained its perfection in

Ireland, and perhaps in part of Wales, about the end of the sixth century, and perhaps about a century after, (on the establishment of Christianity,)

in Saxonised England; for the Irish monastery of Iona founded a colony at Lindisfarne, near Durham, about 634, where the manuscript

from which our specimen is taken, was executed about the year 698.

About the ninth and tenth centuries a distinct Anglo-Saxon style began to develop itself, of which we shall hereafter give specimens.

It was partly founded on the style of which we are now treating, and partly upon a Continental one, which arose from various circumstances

to be discussed hereafter, and whose character consisted principally in adding foliage to the simply intersecting lines.

The style, of which our present specimen is a fine example, and which is formed by a composition of intersecting lines of various colours,

enriched by interwoven creatures of the lizard tribe, is exhibited to us in its remaining monuments, in three or four successive periods of development.

The first period may be distinguished by the grotesque character of the pictures representing the Evangelists, or other human figures,

which are of the rudest possible execution, very closely resembling Mexican remains; and also by the inferiority of the merely decorative

portions, consisting of large letters, enriched with interlaced line-work, which are of much poorer design and execution than our specimen.

This period is well represented by the psalter preserved in St. John's College, Cambridge, of which an example is given in Westwood's

" Paleographia Sacra Pictoria." It may possibly be assigned to as early a period as the early part of the sixth century.

The second period is illustrated by the wonderful volume known as the "Book of Kells;" also described at some length in "Westwood's

Paleographia," &c. In this work the figures partake still of the grotesque character of purely barbaric art; but the decorative letters and

borderings, and other merely ornamental portions, are of a degree of richness, intricacy, and sharpness of execution, unequalled by any

other work of the style, either of a preceding or succeeding period; and in one feature, that of interlaced letters formed of the human

figure, it is unique.

The third period may be illustrated by the beautiful manuscript from which our specimen is taken, which marks a decided improve-

ment in the figure pictures, which have a somewhat Byzantine character; and the merely decorative features, as may be seen in our specimen,

though not equalling the " Book of Kells" in gorgeousness of colour, or in the profusion of enrichment we have alluded to, yet displays

an advance in the direction of harmony, and a certain completeness of style, which always marks the more perfect development of any branch of art.

Fourthly, It may be remarked, that although another style sprang up about the ninth century, still the practice of this style continued

to be exercised in parts of England, and in Ireland and Wales, so late as the eleventh, and even twelfth century; of which the Gospels of

MacDurnan, in Lambeth Palace, of about the eighth century, and the Gospels of Ricemarchus, in Trinity College, Dublin, of the eleventh

century, may be cited as examples; the latter a most beautiful specimen of the style, with some characteristics peculiarly its own.

After this short sketch of the style, and its leading features and progress, it remains to describe somewhat more minutely the beautiful

manuscript from which our specimen is taken.

It is marked in the Cottonian library as Nero, D, 4. This wonderful manuscript, as shown by an entry at the end of the book, in a hand-

writing nearly coeval with the main part of the manuscript, was written by Eadfrith, Abbot of Lindisfarne, in honour of God and St. Cuthbert.

It is also stated that the Monk Githelwald executed the illuminations—facts most important, as fixing the execution of the volume between 698 and

721.*' Many marvellous stories are related by subsequent chroniclers of Durham, respecting miracles, &c, &c, performed by this richly decorated

volume. The first ornamental portion of the book contains the Eusebian canons, enclosed in separate arched compartments, as usual in books of

this and much later periods; but the grandest pages are, as is generally the case, those at the commencement of the four Gospels—the genealogical

portion of the Gospel of St. Matthew having a separate one; and another is placed at the commencement of the Epistle of St. Jerome. Our

specimen is the commencement of the Gospel of St. John. The spare page opposite to the commencement of the Gospels is occupied by a large

square filled with the most intricately wrought patterns of a similar style to those in the large letters in our specimen; and one, in particular, of

these masses of ornament is so rich and various in its detail as almost to bid defiance to the skill of any modern imitation. There is also a picture

of the Evangelist at the commencement of each Gospel, betraying a Byzantine origin of design, though no such influence is traceable in the

pages without figures. These figures, though barbarous in design, are executed with extreme neatness and precision. The other pages in

the book are without ornament, except in one portion, where a smaller kind of capital letter is occasionally employed; such as the one at

the head of this description, a double letter, forming M and A.

It will easily be perceived that the three large letters in our specimen, are I N P; the first letters of "In principium erat verbum, &c, &c."

It will be seen that there is an interlinear Saxon translation of the Latin, possibly of a somewhat more modern date than the rest of the manuscript

* St. Cuthbert died 087. Eadfrith held the see from 698 to 721. (Ethelwald afterwards became Abbot of Lindisfarne, and died 737.