Jewellers Art in France

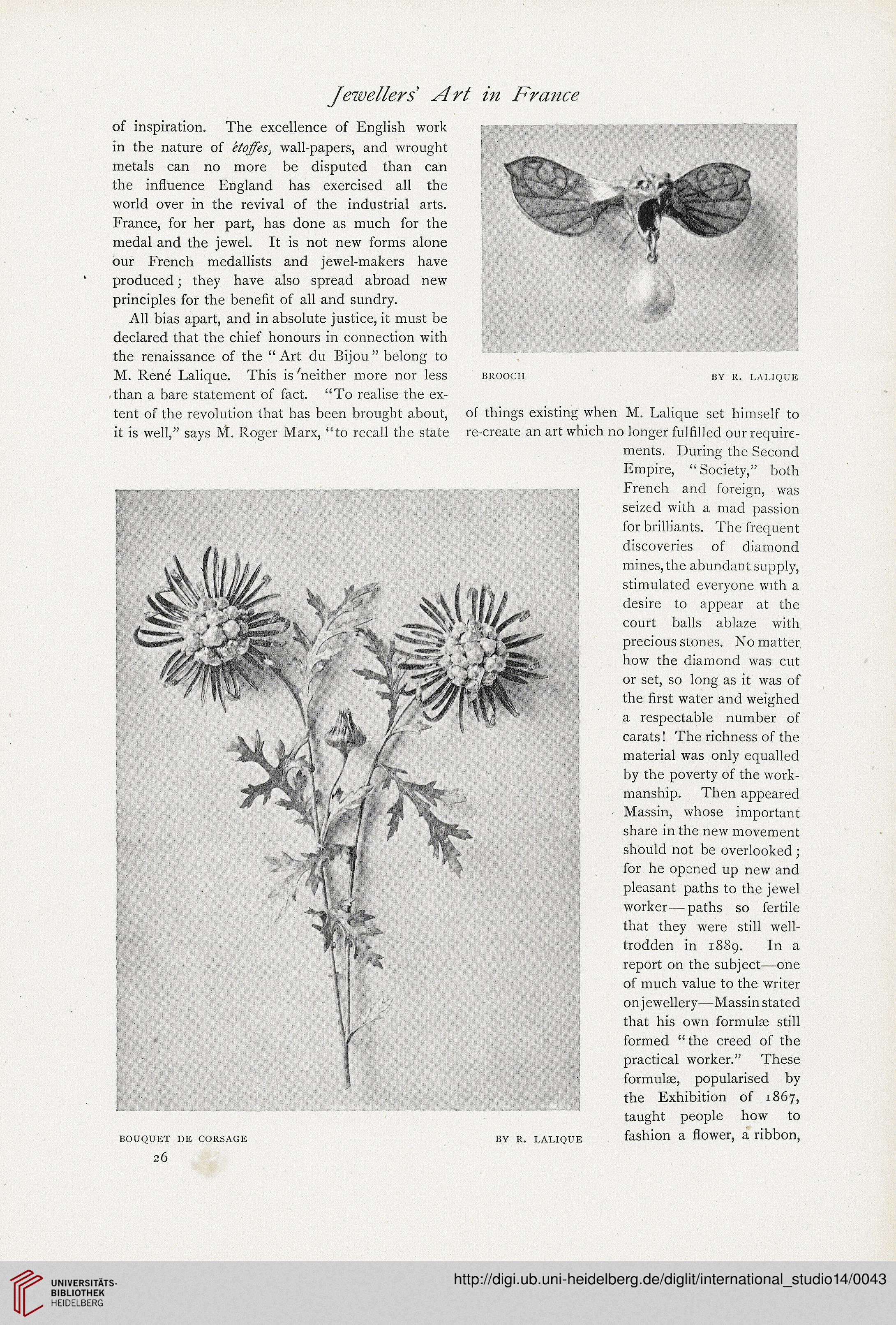

BROOCH

BY R. LALIQUE

of inspiration. The excellence of English work

in the nature of ktoffes, wall-papers, and wrought

metals can no more be disputed than can

the influence England has exercised all the

world over in the revival of the industrial arts.

France, for her part, has done as much for the

medal and the jewel. It is not new forms alone

our French medallists and jewel-makers have

produced; they have also spread abroad new

principles for the benefit of all and sundry.

All bias apart, and in absolute justice, it must be

declared that the chief honours in connection with

the renaissance of the “ Art du Bijou ” belong to

M. Rene Lalique. This is 'neither more nor less

.than a bare statement of fact. “To realise the ex-

tent of the revolution that has been brought about,

it is well,” says ±\1. Roger Marx, “to recall the state

of things existing when M. Lalique set himself to

re-create an art which no longer fulfilled our require-

ments. During the Second

Empire, “Society,” both

French and foreign, was

seized with a mad passion

for brilliants. The frequent

discoveries of diamond

mines, the abundant supply,

stimulated everyone with a

desire to appear at the

court balls ablaze with

precious stones. No matter

how the diamond was cut

or set, so long as it was of

the first water and weighed

a respectable number of

carats! The richness of the

material was only equalled

by the poverty of the work-

manship. Then appeared

Massin, whose important

share in the new movement

should not be overlooked;

for he opened up new and

pleasant paths to the jewel

worker— paths so fertile

that they were still well-

trodden in 1889. In a

report on the subject—one

of much value to the writer

on jewellery—Massin stated

that his own formulae still

formed “the creed of the

practical worker.” These

formulae, popularised by

the Exhibition of 1867,

taught people how to

fashion a flower, a ribbon,

BOUQUET DE CORSAGE

BY R. LALIQUE

26

BROOCH

BY R. LALIQUE

of inspiration. The excellence of English work

in the nature of ktoffes, wall-papers, and wrought

metals can no more be disputed than can

the influence England has exercised all the

world over in the revival of the industrial arts.

France, for her part, has done as much for the

medal and the jewel. It is not new forms alone

our French medallists and jewel-makers have

produced; they have also spread abroad new

principles for the benefit of all and sundry.

All bias apart, and in absolute justice, it must be

declared that the chief honours in connection with

the renaissance of the “ Art du Bijou ” belong to

M. Rene Lalique. This is 'neither more nor less

.than a bare statement of fact. “To realise the ex-

tent of the revolution that has been brought about,

it is well,” says ±\1. Roger Marx, “to recall the state

of things existing when M. Lalique set himself to

re-create an art which no longer fulfilled our require-

ments. During the Second

Empire, “Society,” both

French and foreign, was

seized with a mad passion

for brilliants. The frequent

discoveries of diamond

mines, the abundant supply,

stimulated everyone with a

desire to appear at the

court balls ablaze with

precious stones. No matter

how the diamond was cut

or set, so long as it was of

the first water and weighed

a respectable number of

carats! The richness of the

material was only equalled

by the poverty of the work-

manship. Then appeared

Massin, whose important

share in the new movement

should not be overlooked;

for he opened up new and

pleasant paths to the jewel

worker— paths so fertile

that they were still well-

trodden in 1889. In a

report on the subject—one

of much value to the writer

on jewellery—Massin stated

that his own formulae still

formed “the creed of the

practical worker.” These

formulae, popularised by

the Exhibition of 1867,

taught people how to

fashion a flower, a ribbon,

BOUQUET DE CORSAGE

BY R. LALIQUE

26