Enamelling

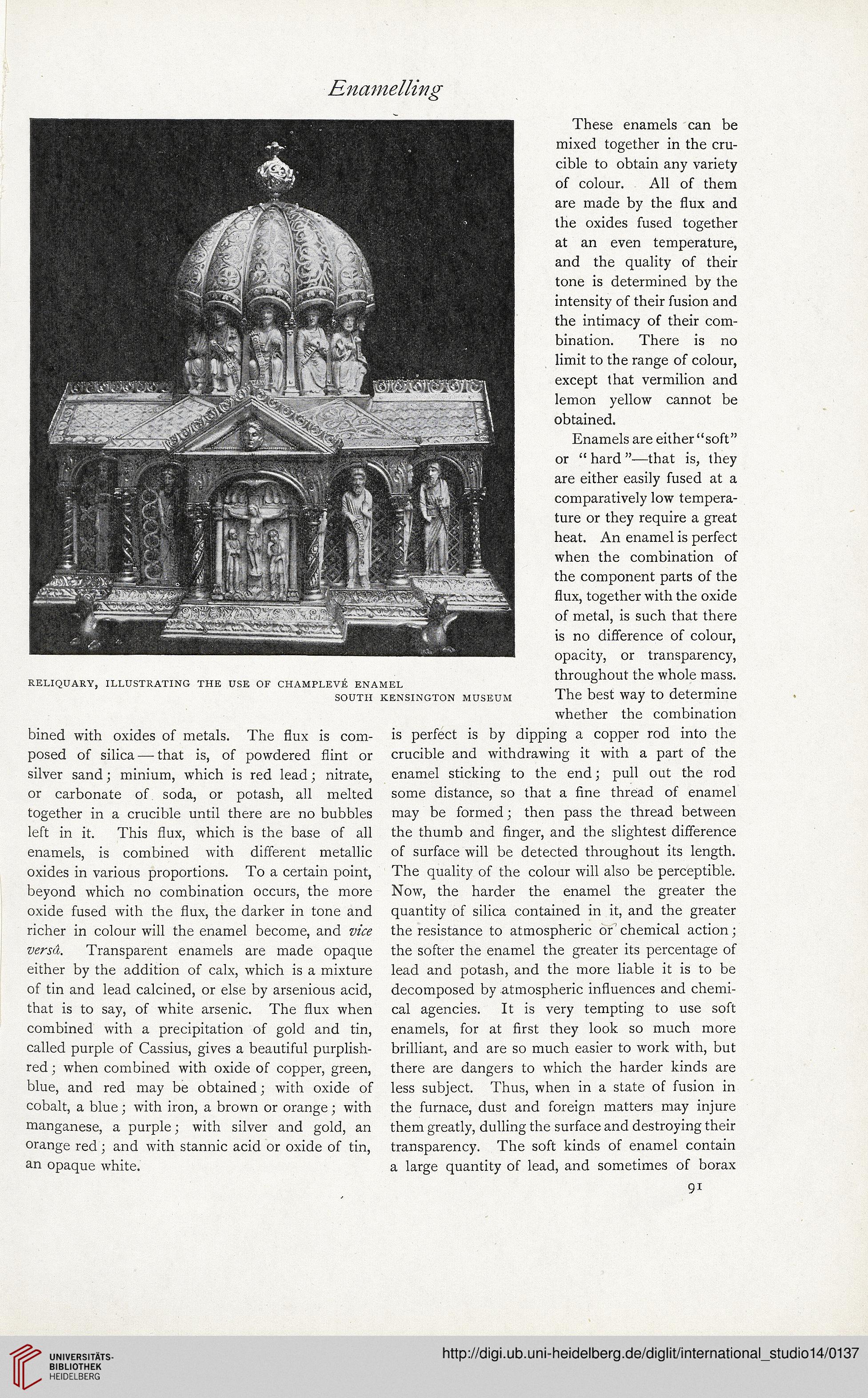

RELIQUARY, ILLUSTRATING THE USE OF CHAMPLEVE ENAMEL

SOUTH KENSINGTON MUSEUM

bined with oxides of metals. The flux is com-

posed of silica — that is, of powdered flint or

silver sand; minium, which is red lead; nitrate,

or carbonate of soda, or potash, all melted

together in a crucible until there are no bubbles

left in it. This flux, which is the base of all

enamels, is combined with different metallic

oxides in various proportions. To a certain point,

beyond which no combination occurs, the more

oxide fused with the flux, the darker in tone and

richer in colour will the enamel become, and vice

versa. Transparent enamels are made opaque

either by the addition of calx, which is a mixture

of tin and lead calcined, or else by arsenious acid,

that is to say, of white arsenic. The flux when

combined with a precipitation of gold and tin,

called purple of Cassius, gives a beautiful purplish-

red ; when combined with oxide of copper, green,

blue, and red may be obtained; with oxide of

cobalt, a blue; with iron, a brown or orange; with

manganese, a purple; with silver and gold, an

orange red; and with stannic acid or oxide of tin,

an opaque white.

These enamels can be

mixed together in the cru-

cible to obtain any variety

of colour. All of them

are made by the flux and

the oxides fused together

at an even temperature,

and the quality of their

tone is determined by the

intensity of their fusion and

the intimacy of their com-

bination. There is no

limit to the range of colour,

except that vermilion and

lemon yellow cannot be

obtained.

Enamels are either “soft”

or “ hard ”—that is, they

are either easily fused at a

comparatively low tempera-

ture or they require a great

heat. An enamel is perfect

when the combination of

the component parts of the

flux, together with the oxide

of metal, is such that there

is no difference of colour,

opacity, or transparency,

throughout the whole mass.

The best way to determine

whether the combination

is perfect is by dipping a copper rod into the

crucible and withdrawing it with a part of the

enamel sticking to the end; pull out the rod

some distance, so that a fine thread of enamel

may be formed; then pass the thread between

the thumb and finger, and the slightest difference

of surface will be detected throughout its length.

The quality of the colour will also be perceptible.

Now, the harder the enamel the greater the

quantity of silica contained in it, and the greater

the resistance to atmospheric or" chemical action;

the softer the enamel the greater its percentage of

lead and potash, and the more liable it is to be

decomposed by atmospheric influences and chemi-

cal agencies. It is very tempting to use soft

enamels, for at first they look so much more

brilliant, and are so much easier to work with, but

there are dangers to which the harder kinds are

less subject. Thus, when in a state of fusion in

the furnace, dust and foreign matters may injure

them greatly, dulling the surface and destroying their

transparency. The soft kinds of enamel contain

a large quantity of lead, and sometimes of borax

91

RELIQUARY, ILLUSTRATING THE USE OF CHAMPLEVE ENAMEL

SOUTH KENSINGTON MUSEUM

bined with oxides of metals. The flux is com-

posed of silica — that is, of powdered flint or

silver sand; minium, which is red lead; nitrate,

or carbonate of soda, or potash, all melted

together in a crucible until there are no bubbles

left in it. This flux, which is the base of all

enamels, is combined with different metallic

oxides in various proportions. To a certain point,

beyond which no combination occurs, the more

oxide fused with the flux, the darker in tone and

richer in colour will the enamel become, and vice

versa. Transparent enamels are made opaque

either by the addition of calx, which is a mixture

of tin and lead calcined, or else by arsenious acid,

that is to say, of white arsenic. The flux when

combined with a precipitation of gold and tin,

called purple of Cassius, gives a beautiful purplish-

red ; when combined with oxide of copper, green,

blue, and red may be obtained; with oxide of

cobalt, a blue; with iron, a brown or orange; with

manganese, a purple; with silver and gold, an

orange red; and with stannic acid or oxide of tin,

an opaque white.

These enamels can be

mixed together in the cru-

cible to obtain any variety

of colour. All of them

are made by the flux and

the oxides fused together

at an even temperature,

and the quality of their

tone is determined by the

intensity of their fusion and

the intimacy of their com-

bination. There is no

limit to the range of colour,

except that vermilion and

lemon yellow cannot be

obtained.

Enamels are either “soft”

or “ hard ”—that is, they

are either easily fused at a

comparatively low tempera-

ture or they require a great

heat. An enamel is perfect

when the combination of

the component parts of the

flux, together with the oxide

of metal, is such that there

is no difference of colour,

opacity, or transparency,

throughout the whole mass.

The best way to determine

whether the combination

is perfect is by dipping a copper rod into the

crucible and withdrawing it with a part of the

enamel sticking to the end; pull out the rod

some distance, so that a fine thread of enamel

may be formed; then pass the thread between

the thumb and finger, and the slightest difference

of surface will be detected throughout its length.

The quality of the colour will also be perceptible.

Now, the harder the enamel the greater the

quantity of silica contained in it, and the greater

the resistance to atmospheric or" chemical action;

the softer the enamel the greater its percentage of

lead and potash, and the more liable it is to be

decomposed by atmospheric influences and chemi-

cal agencies. It is very tempting to use soft

enamels, for at first they look so much more

brilliant, and are so much easier to work with, but

there are dangers to which the harder kinds are

less subject. Thus, when in a state of fusion in

the furnace, dust and foreign matters may injure

them greatly, dulling the surface and destroying their

transparency. The soft kinds of enamel contain

a large quantity of lead, and sometimes of borax

91