R. IV. Allan

discussed with reverent enthusiasm. In 1875,

the year of Robert Allan’s arrival in Paris,

Lepage exhibited his pathetic and masterly Petite

Communion and the more ambitious Bergers,

which were received with a chorus of admiration

from artists, though the lay critics looked coldly

on their vivid realism ; whilst in 1880, just before

Mr. Allan left Paris, appeared the Joan of Arc, in

which the gifted young Frenchman may be said to

have touched his highest point of excellence.

Robert Allan’s student time coincided therefore

with the art career of Lepage, who exercised

perhaps more influence on him than did any of

the men under whose direct criticism he studied.

He was, however, from first to last, too thoroughly

individual to owe much to any other artist, and

out of the conflicting elements of the French

ateliers he emerged more British than ever. No

false pride spoiled the simplicity of the art student’s

life in those happy days, and anyone who looks

into Mr. Allan’s humorous face and notes the

merry twinkle in his eye as he tells some amusing

incident from the long-ago, can well imagine what

a bright Bohemian life he and his chum led in

the big, bare studio, with its walls covered with

sketches and studies. The address perhaps was

rather against the new quarters, for this ideal

studio was in the Boulevard d’Enfer, a name

perhaps not altogether inapplicable to some of

the neighbouring ateliers. Here real home-made

porridge was eaten, a store of the wherewithal

having been sent for from the northern home in a

goodly sack, after several unsuccessful attempts

had been made to procure it in the restaurants.

The spirited restaurateur, indeed, had got the real

thing, and his chef-de-cuisine had learnt to turn it

out well; but, then, the exorbitant price of 60 cen-

times a plate was charged, for the farine d’avoine

had been bought at the pharmaciens in tiny packets

sold as a medicine—for what ailment was not

specified, though it may possibly have been home-

sickness. The Scotch songs sung, the wild

reels danced in Mr. Allan’s studio, which some-

times alarmed the natives admitted to a share in

the revels, kept home memories alive even in the

Boulevard d’Enfer, proving how just was the

criticism of the Frenchman who said that if two

Englishmen were thrown on a desert island they

would not speak to each other till a third ship-

wrecked fellow-countryman arrived to introduce

them to each other, but that if the same mis-

fortune befell two Scotchmen they would have

founded a Caledonian club before the week

was out.

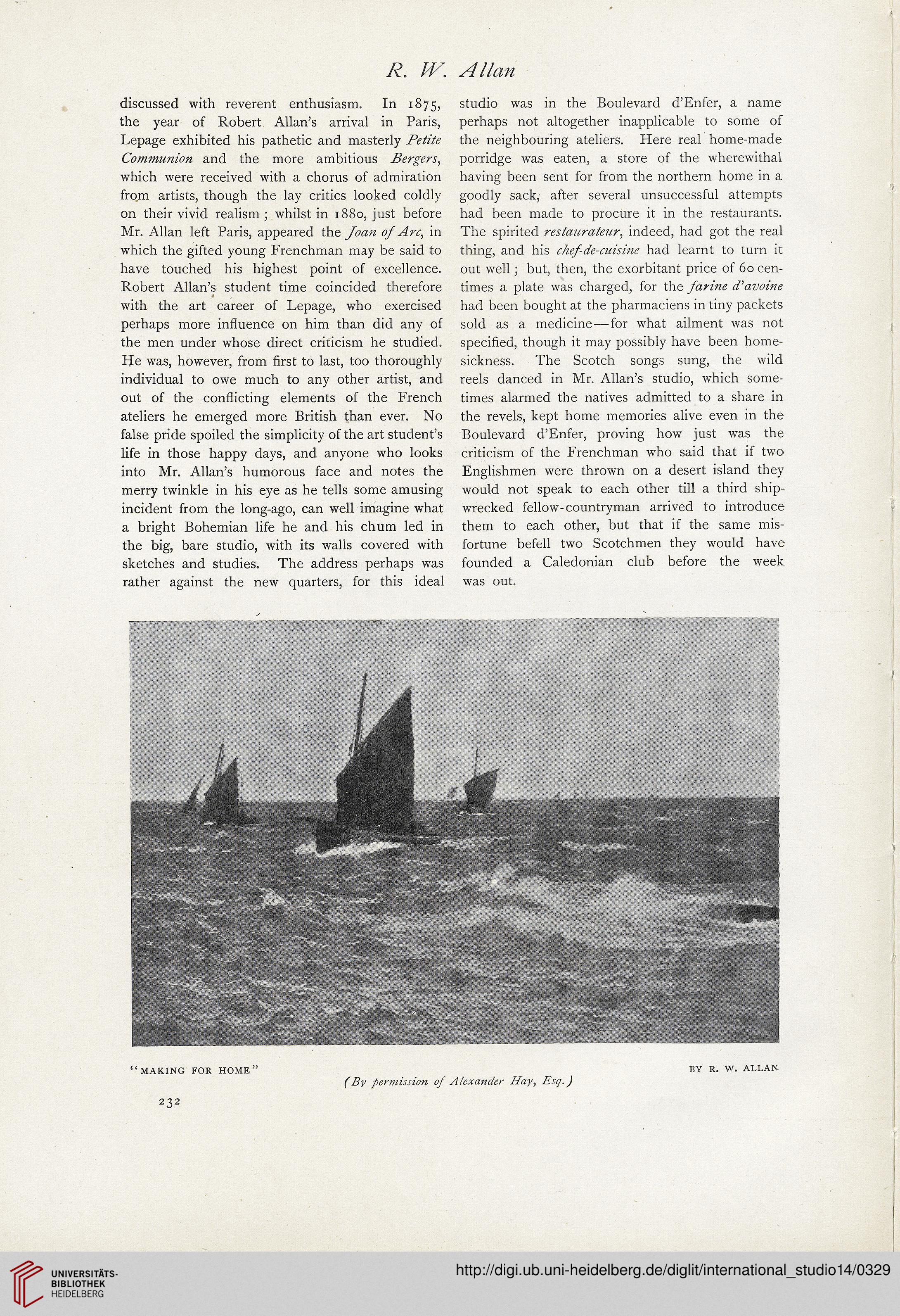

“MAKING FOR HOME”

232

(By permission of Alexander Hay, Esq.)

BY R. W. ALLAN

discussed with reverent enthusiasm. In 1875,

the year of Robert Allan’s arrival in Paris,

Lepage exhibited his pathetic and masterly Petite

Communion and the more ambitious Bergers,

which were received with a chorus of admiration

from artists, though the lay critics looked coldly

on their vivid realism ; whilst in 1880, just before

Mr. Allan left Paris, appeared the Joan of Arc, in

which the gifted young Frenchman may be said to

have touched his highest point of excellence.

Robert Allan’s student time coincided therefore

with the art career of Lepage, who exercised

perhaps more influence on him than did any of

the men under whose direct criticism he studied.

He was, however, from first to last, too thoroughly

individual to owe much to any other artist, and

out of the conflicting elements of the French

ateliers he emerged more British than ever. No

false pride spoiled the simplicity of the art student’s

life in those happy days, and anyone who looks

into Mr. Allan’s humorous face and notes the

merry twinkle in his eye as he tells some amusing

incident from the long-ago, can well imagine what

a bright Bohemian life he and his chum led in

the big, bare studio, with its walls covered with

sketches and studies. The address perhaps was

rather against the new quarters, for this ideal

studio was in the Boulevard d’Enfer, a name

perhaps not altogether inapplicable to some of

the neighbouring ateliers. Here real home-made

porridge was eaten, a store of the wherewithal

having been sent for from the northern home in a

goodly sack, after several unsuccessful attempts

had been made to procure it in the restaurants.

The spirited restaurateur, indeed, had got the real

thing, and his chef-de-cuisine had learnt to turn it

out well; but, then, the exorbitant price of 60 cen-

times a plate was charged, for the farine d’avoine

had been bought at the pharmaciens in tiny packets

sold as a medicine—for what ailment was not

specified, though it may possibly have been home-

sickness. The Scotch songs sung, the wild

reels danced in Mr. Allan’s studio, which some-

times alarmed the natives admitted to a share in

the revels, kept home memories alive even in the

Boulevard d’Enfer, proving how just was the

criticism of the Frenchman who said that if two

Englishmen were thrown on a desert island they

would not speak to each other till a third ship-

wrecked fellow-countryman arrived to introduce

them to each other, but that if the same mis-

fortune befell two Scotchmen they would have

founded a Caledonian club before the week

was out.

“MAKING FOR HOME”

232

(By permission of Alexander Hay, Esq.)

BY R. W. ALLAN