Gordon Craig

glitter of water. His craftsmanship is the tool of a

finely decorative sense; he has telling composition,

a generous instinct for spacing, and a keen eye for

the dramatic possibilities. His judgment under-

stands the limits of a medium as unerringly as it

grips the essential values of the things expressed,

whether it be a bookplate or a death-scene in an

opera.

What are called, with large-lettered pride of adver-

tisement, “ spectacular effects ” on the stage,

whether in opera or the playhouse, are not only in

themselves somewhat crude and childish in their

appeal to the adult imagination, but they have also

a confusing result upon the opera or play to which

they are the sCenic setting, in that they draw away

the attention of the onlooker from the music or

the words, as well as from the action of the charac-

ters, all of which, by consequence, instead of

dominating the performance, become but a mad

part of the resulting wrangle, perplexing the wits

in a confusing blare to eye and ear. To the

acting, to the individual action of the players, to

the emotions which it is the whole province of

the dramatic arts to arouse, this scenic over-

elaboration is absolutely disastrous—the actors

becoming but mere specks upon the landscape.

This “ spectacular ” vice is most flauntingly

displayed in Opera and the Poetic Drama. Now

Opera, since it relies on reaching our emotions

through the instrumentality of music (the words

at best being rarely heard, except by those who

already know them) can never have so direct an

appeal to man’s imagination or his emotions as

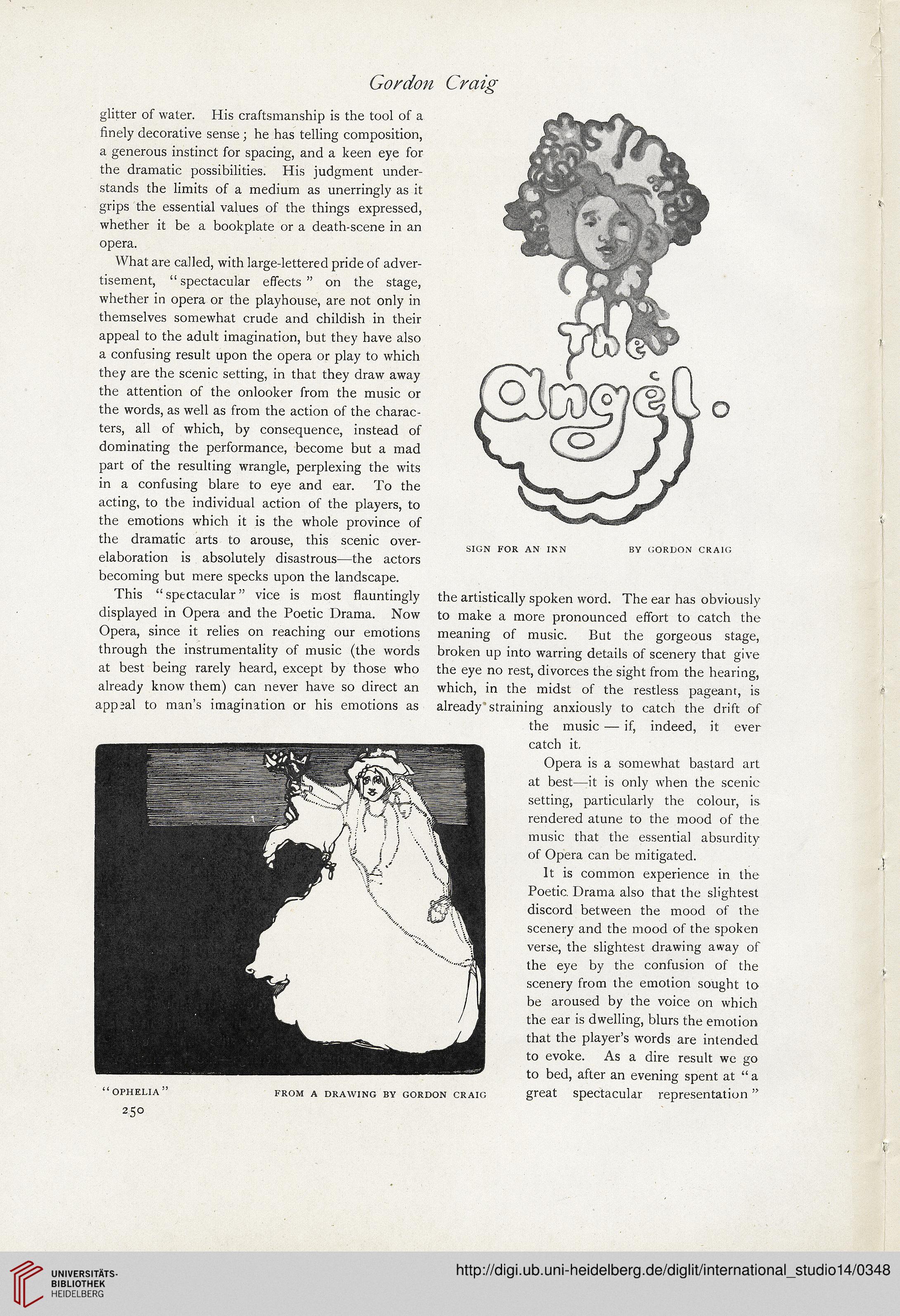

SIGN FOR AN INN BY GORDON CRAIG

the artistically spoken word. The ear has obviously

to make a more pronounced effort to catch the

meaning of music. But the gorgeous stage,

broken up into warring details of scenery that give

the eye no rest, divorces the sight from the hearing,

which, in the midst of the restless pageant, is

already" straining anxiously to catch the drift of

the music — if, indeed, it ever

catch it.

Opera is a somewhat bastard art

at best—it is only when the scenic

setting, particularly the colour, is

rendered atune to the mood of the

music that the essential absurdity

of Opera can be mitigated.

It is common experience in the

Poetic. Drama also that the slightest

discord between the mood of the

scenery and the mood of the spoken

verse, the slightest drawing away of

the eye by the confusion of the

scenery from the emotion sought to

be aroused by the voice on which

the ear is dwelling, blurs the emotion

that the player’s words are intended

to evoke. As a dire result we go

to bed, after an evening spent at “ a

great spectacular representation ”

FROM A DRAWING BY GORDON CRAIG

“ OPHELIA ”

250

glitter of water. His craftsmanship is the tool of a

finely decorative sense; he has telling composition,

a generous instinct for spacing, and a keen eye for

the dramatic possibilities. His judgment under-

stands the limits of a medium as unerringly as it

grips the essential values of the things expressed,

whether it be a bookplate or a death-scene in an

opera.

What are called, with large-lettered pride of adver-

tisement, “ spectacular effects ” on the stage,

whether in opera or the playhouse, are not only in

themselves somewhat crude and childish in their

appeal to the adult imagination, but they have also

a confusing result upon the opera or play to which

they are the sCenic setting, in that they draw away

the attention of the onlooker from the music or

the words, as well as from the action of the charac-

ters, all of which, by consequence, instead of

dominating the performance, become but a mad

part of the resulting wrangle, perplexing the wits

in a confusing blare to eye and ear. To the

acting, to the individual action of the players, to

the emotions which it is the whole province of

the dramatic arts to arouse, this scenic over-

elaboration is absolutely disastrous—the actors

becoming but mere specks upon the landscape.

This “ spectacular ” vice is most flauntingly

displayed in Opera and the Poetic Drama. Now

Opera, since it relies on reaching our emotions

through the instrumentality of music (the words

at best being rarely heard, except by those who

already know them) can never have so direct an

appeal to man’s imagination or his emotions as

SIGN FOR AN INN BY GORDON CRAIG

the artistically spoken word. The ear has obviously

to make a more pronounced effort to catch the

meaning of music. But the gorgeous stage,

broken up into warring details of scenery that give

the eye no rest, divorces the sight from the hearing,

which, in the midst of the restless pageant, is

already" straining anxiously to catch the drift of

the music — if, indeed, it ever

catch it.

Opera is a somewhat bastard art

at best—it is only when the scenic

setting, particularly the colour, is

rendered atune to the mood of the

music that the essential absurdity

of Opera can be mitigated.

It is common experience in the

Poetic. Drama also that the slightest

discord between the mood of the

scenery and the mood of the spoken

verse, the slightest drawing away of

the eye by the confusion of the

scenery from the emotion sought to

be aroused by the voice on which

the ear is dwelling, blurs the emotion

that the player’s words are intended

to evoke. As a dire result we go

to bed, after an evening spent at “ a

great spectacular representation ”

FROM A DRAWING BY GORDON CRAIG

“ OPHELIA ”

250