Robert Sterl

settled in its capital, Dresden. Yet it only houses

him for about half the year—the winter season,

during which he spends a considerable time teach-

ing classes. Half his interests are centred in

Hessia, and he feels drawn to that soil as another

would to his native country. Repeated sketch-

ing tours thither with friends have made him

enamoured of those parts, and at last he built

himself a small house there, merely a studio and

a couple of rooms, at Winninghausen, two hours

from the next railroad station, three from Frankfort-

on-the-Main. To spend a season so far removed

from all comfort is a tax upon almost anyone, but

the past summer—with its splendid percentage of

fine days—well repaid him with its opportunities of

work for any inconveniences he may have had to

suffer. It was the first summer he has spent altogether

at Winninghausen, and it was a most fruitful one.

Taken altogether, his love of simplicity and his

selection as to form still hold good, but he has

learned to take more delight in colour. What his

landscape art may have lost in refined harmony it has

gained in freshness. There

are delightful sketches of

juicy green meadows,

watered by glittering

brooks against a bright

blue sky, among this last

year’s work. Confronted

so much during the height

of summer with a luxurious

bit of country, he has been

attracted more than

formerly by problems of

intense sunlight. The

labourer, for example,

seated at the brink of a

clay pit, was painted in

full midsummer sun ; the

sketch is glaring with reds

and yellows, and one of

the most powerful present-

ations of sunshine imagin-

able. This is but a

sketch, to be utilised in

some future painting.

Among the finished paint-

ings with a similar pro-

blem, there is a specially

fascinating one called the

Return from the Field. A

farmer, his wife and a child

are returning home from

their day’s work across a

meadow that lies in the shadow of a dark forest in

the middle distance. As the setting sun (not visible

itself) is behind this forest, this, too, presents

to our eye a sombre, quiet silhouette. But

beyond and below it in the perspective the last

golden rays fall upon some distant trees that are

lighted up in a blaze and form a most telling

contrast to the subdued quiet of all the fore-

ground and middle distance.

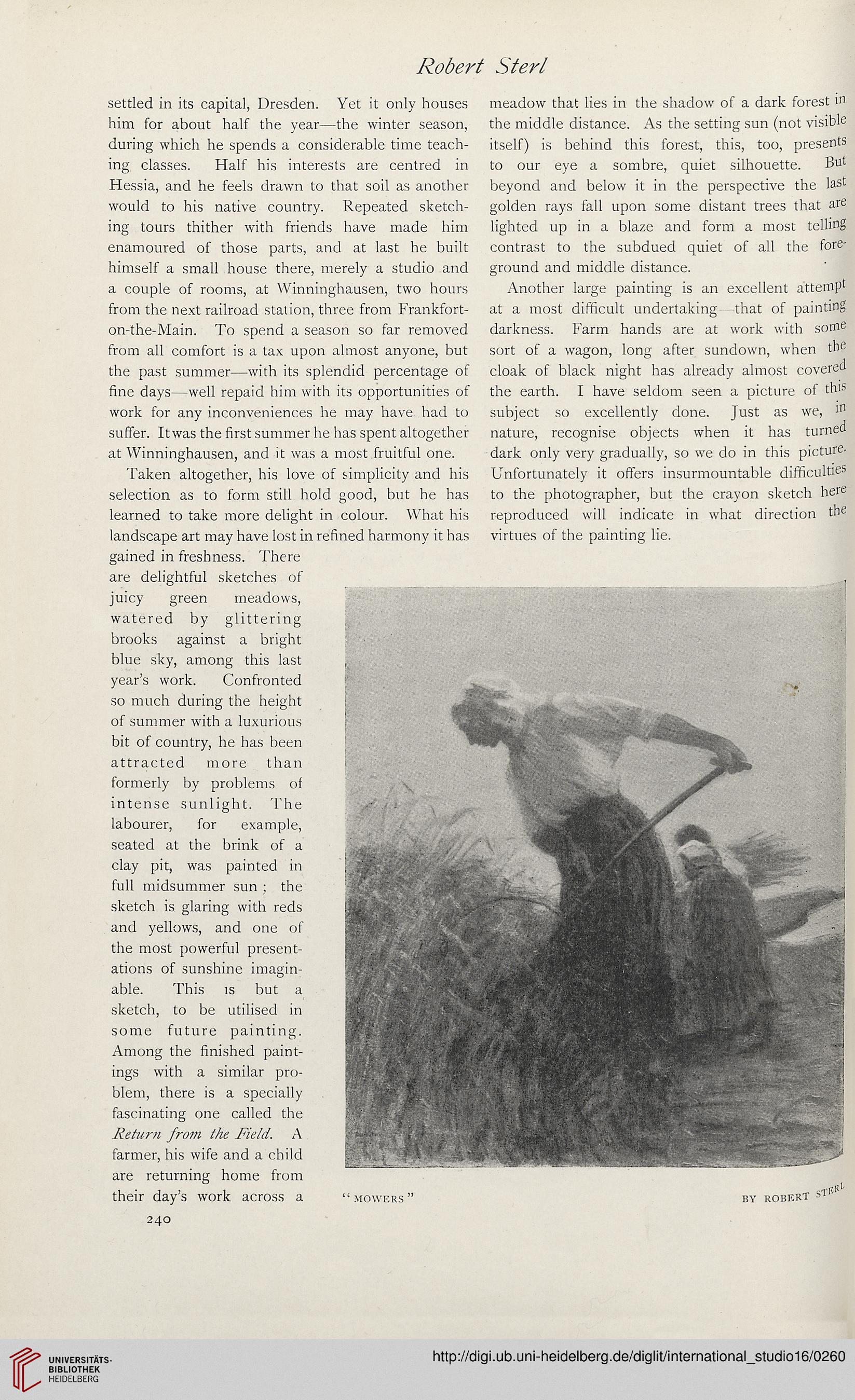

Another large painting is an excellent attempt

at a most difficult undertaking—that of painting

darkness. Farm hands are at work with some

sort of a wagon, long after sundown, when the

cloak of black night has already almost covered

the earth. I have seldom seen a picture of this

subject so excellently done. Just as we, m

nature, recognise objects when it has turned

dark only very gradually, so we do in this picture-

Unfortunately it offers insurmountable difficulties

to the photographer, but the crayon sketch here

reproduced will indicate in what direction the

virtues of the painting lie.

240

settled in its capital, Dresden. Yet it only houses

him for about half the year—the winter season,

during which he spends a considerable time teach-

ing classes. Half his interests are centred in

Hessia, and he feels drawn to that soil as another

would to his native country. Repeated sketch-

ing tours thither with friends have made him

enamoured of those parts, and at last he built

himself a small house there, merely a studio and

a couple of rooms, at Winninghausen, two hours

from the next railroad station, three from Frankfort-

on-the-Main. To spend a season so far removed

from all comfort is a tax upon almost anyone, but

the past summer—with its splendid percentage of

fine days—well repaid him with its opportunities of

work for any inconveniences he may have had to

suffer. It was the first summer he has spent altogether

at Winninghausen, and it was a most fruitful one.

Taken altogether, his love of simplicity and his

selection as to form still hold good, but he has

learned to take more delight in colour. What his

landscape art may have lost in refined harmony it has

gained in freshness. There

are delightful sketches of

juicy green meadows,

watered by glittering

brooks against a bright

blue sky, among this last

year’s work. Confronted

so much during the height

of summer with a luxurious

bit of country, he has been

attracted more than

formerly by problems of

intense sunlight. The

labourer, for example,

seated at the brink of a

clay pit, was painted in

full midsummer sun ; the

sketch is glaring with reds

and yellows, and one of

the most powerful present-

ations of sunshine imagin-

able. This is but a

sketch, to be utilised in

some future painting.

Among the finished paint-

ings with a similar pro-

blem, there is a specially

fascinating one called the

Return from the Field. A

farmer, his wife and a child

are returning home from

their day’s work across a

meadow that lies in the shadow of a dark forest in

the middle distance. As the setting sun (not visible

itself) is behind this forest, this, too, presents

to our eye a sombre, quiet silhouette. But

beyond and below it in the perspective the last

golden rays fall upon some distant trees that are

lighted up in a blaze and form a most telling

contrast to the subdued quiet of all the fore-

ground and middle distance.

Another large painting is an excellent attempt

at a most difficult undertaking—that of painting

darkness. Farm hands are at work with some

sort of a wagon, long after sundown, when the

cloak of black night has already almost covered

the earth. I have seldom seen a picture of this

subject so excellently done. Just as we, m

nature, recognise objects when it has turned

dark only very gradually, so we do in this picture-

Unfortunately it offers insurmountable difficulties

to the photographer, but the crayon sketch here

reproduced will indicate in what direction the

virtues of the painting lie.

240