fnr^HEWORK OF ALBERT PAUL

] BESNARD. BY MRS. FRANCES

1 KEYZER.

A FRENCHMAN every inch of him, and essentialiy

French as an artist is M. Albert Paul Besnard,

although the English influence during his two

years' sojourn in the land of Turner and Rossetti

has left its mark upon his work, and this influence

is especially noticeable in his marine pieces and his

studies of Algerian life. It is interesting to know

something of the man who has succeeded in im-

pressing us with the charm of his colouring, with

those delightful pastels that recall a glorious sunset

with the eyes of a woman gleaming through the

purples and gold, the mauves, and the luminous

pinks; and it was with something that savoured

of a sensation that I approached M. Besnard,

expectant of a strong personality, of an originality

that would explain this wonderful conception of

colour so brilliantly transmitted to his canvases.

I found a largely-built man with a pleasant, good-

humoured expression, a man of some fifty years

of age. A husband and a father—a family man

in every sense of the term—living at his ease in a

" hotel" constructed after his own plans, with

commodious studios and unpretentious sitting-

rooms. A man with a pronounced taste for sport,

outwardly translated in checks of huge dimensions

in place of the traditional velvet; to be met on

days with the reins between his talented

fingers, with his wife beside him and children in

the rumble overweighting a light cart, smiling

his content at the good things it has pleased

Providence to send him.

I also found originality, but not where I expected

it. To quote his own words : " I paint while I

sing canons and fugues." Need it be said that

M. Besnard is no musician ? He has the power

of hearing without noticing sound; a fact that

is singular. This he explained by saying that he

does not listen, and is, therefore, no more affected

by music than by any other noise. From an

artistic point of view it seems extraordinary that a

man who paints with such brilliant arrangement

of colour, with the softly-blended tones that are

so admirable in his work, should be devoid of the

sense of music; that the Mass in D, Fidelio,

Orpheus, the weird passion of Chopin, should be

a dead language to him ! A man's eye may be

more developed than his ear, but to be deaf

to the symphony of sound is a loss that appears

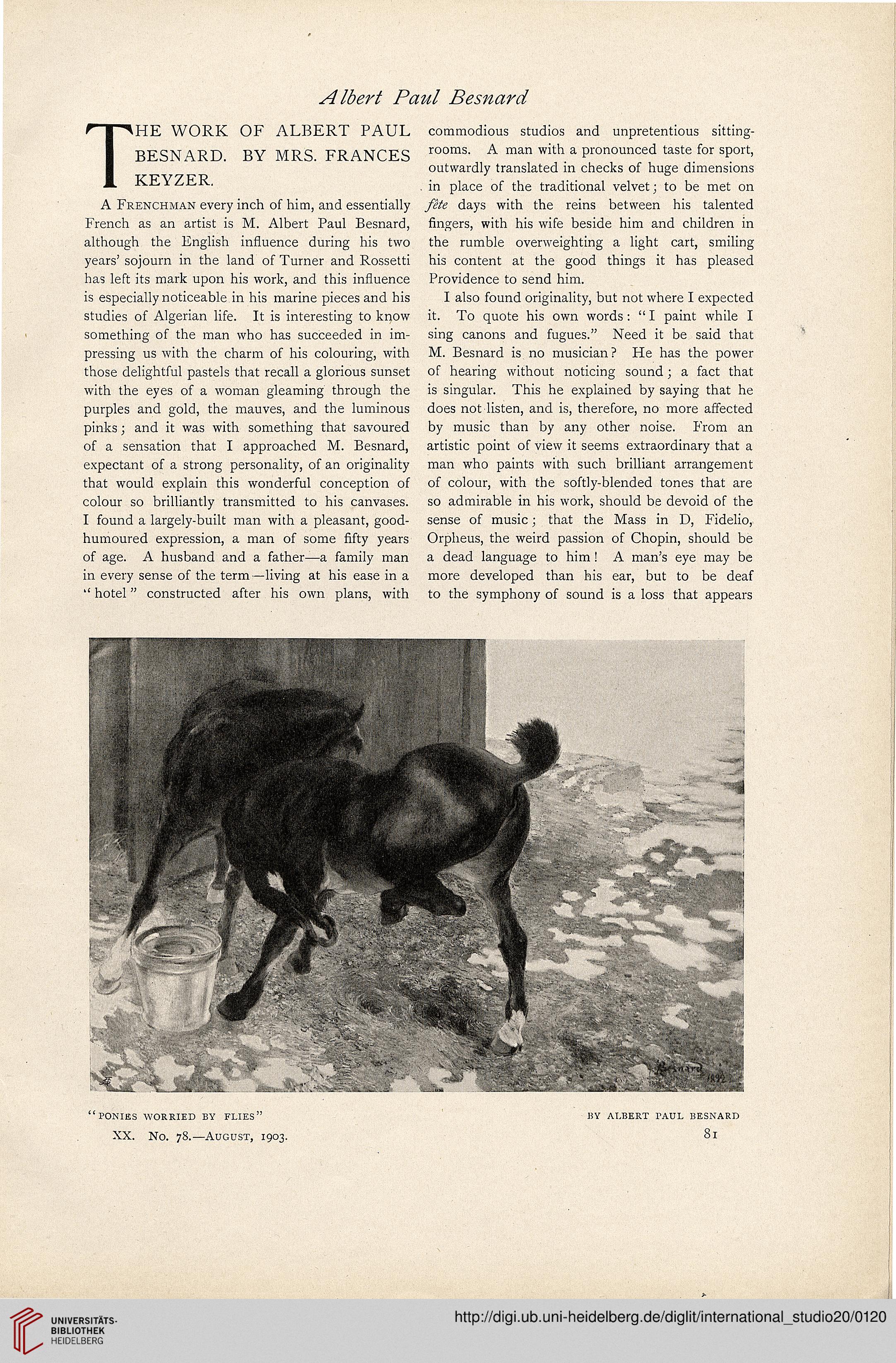

"PONIES WORRIED BY FLIES"

XX. No. 78.—AUGUST, 1903.

BY ALBERT PAUL BESNARD