Ornamental Bookbmding in Ireiand

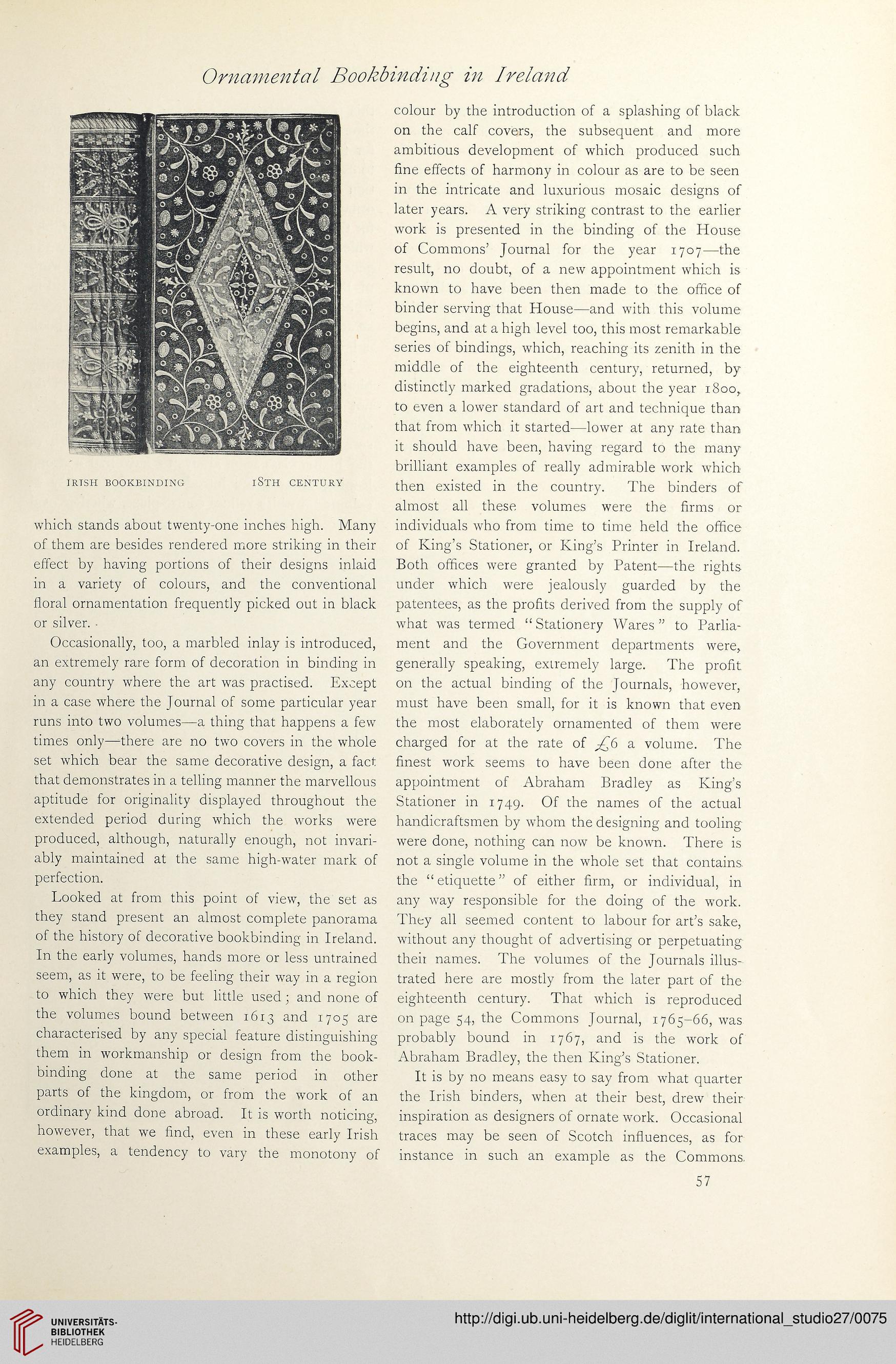

IRTSH BOOKBINDING iSTH CENTURY

which Stands about twenty-one inches high. Many

of them are besides rendered more striking in their

effect by having portions of their designs inlaid

in a variety of colours, and the conventional

floral ornamentation frequently picked out in black

or silver. -

Occasionally, too, a marbled inlay is introduced,

an extremely rare form of decoration in binding in

any country where the art was practised. Except

in a case where the Journal of some particular year

runs into two volumes—a thing that happens a few

times only—there are no two covers in the whole

set which bear the same decorative design, a fact

that demonstrates in a telling manner the marvellous

aptitude for originality displayed throughout the

extended period during which the works were

produced, although, naturally enough, not invari-

ably maintained at the same high-water mark of

perfection.

Looked at from this point of view, the set as

they stand present an almost complete panorama

of the history of decorative bookbinding in Ireiand.

In the early volumes, hands more or less untrained

seem, as it were, to be feeling their way in a region

to which they were but little used; and none of

the volumes bound between 1613 and 1705 are

characterised by any special feature distinguishing

them in workmanship or design from the book-

binding done at the same period in other

parts of the kingdom, or from the work of an

ordinary kind done abroad. It is worth noticing,

however, that we find, even in these early Irish

examples, a tendency to vary the monotony of

colour by the introduction of a splashing of black

on the calf covers, the subsequent and more

ambitious development of which produced such

fine effects of harmony in colour as are to be seen

in the intricate and luxurious mosaic designs of

later years. A very striking contrast to the earlier

work is presented in the binding of the House

of Commons’ Journal for the year 1707—the

result, no doubt, of a new appointment which is

known to have been then made to the office of

binder serving that House—and with this volume

begins, and at a high level too, this most remarkable

series of bindings, which, reaching its zenith in the

middle of the eighteenth Century, returned, by

distinctly marked gradations, about the year 1800,.

to even a lower Standard of art and technique than

that from which it started—lower at any rate than

it should have been, having regard to the many

brilliant examples of really admirable work which

then existed in the country. The binders of

almost all these volumes were the firms or

individuals who from time to time held the office

of King’s Stationer, or King’s Printer in Ireiand.

Both offices were granted by Patent—the rights

uncler which were jealously guarded by the

patentees, as the profits derived from the supply of

what was termed “ Stationery Wares” to Parlia-

ment and the Government departments were,

generally speaking, extremely large. The profit

on the actual binding of the Journals, however,

must have been small, for it is known that even

the most elaborately ornamented of them were

charged for at the rate of £6 a volume. The

finest work seems to have been done after the

appointment of Abraham Bradley as King’s

Stationer in 1749. Of the names of the actual

handicraftsmen by whom the designing and tooling

were done, nothing can now be known. There is

not a single volume in the whole set that contains.

the “etiquette” of either firm, or individual, in

any way responsible for the doing of the work.

They all seemed content to labour for art’s sake,

without any thought of advertising or perpetuating

theii names. The volumes of the Journals illus-

trated here are mostly from the later part of the

eighteenth Century. That which is reproduced

on page 54, the Commons Journal, 1765-66, was

probably bound in 1767, and is the work of

Abraham Bradley, the then King’s Stationer.

It is by no means easy to say from what quarter

the Irish binders, when at their best, drew their

inspiration as designers of ornate work. Occasional

traces may be seen of Scotch influences, as for

instance in such an example as the Commons.

57

IRTSH BOOKBINDING iSTH CENTURY

which Stands about twenty-one inches high. Many

of them are besides rendered more striking in their

effect by having portions of their designs inlaid

in a variety of colours, and the conventional

floral ornamentation frequently picked out in black

or silver. -

Occasionally, too, a marbled inlay is introduced,

an extremely rare form of decoration in binding in

any country where the art was practised. Except

in a case where the Journal of some particular year

runs into two volumes—a thing that happens a few

times only—there are no two covers in the whole

set which bear the same decorative design, a fact

that demonstrates in a telling manner the marvellous

aptitude for originality displayed throughout the

extended period during which the works were

produced, although, naturally enough, not invari-

ably maintained at the same high-water mark of

perfection.

Looked at from this point of view, the set as

they stand present an almost complete panorama

of the history of decorative bookbinding in Ireiand.

In the early volumes, hands more or less untrained

seem, as it were, to be feeling their way in a region

to which they were but little used; and none of

the volumes bound between 1613 and 1705 are

characterised by any special feature distinguishing

them in workmanship or design from the book-

binding done at the same period in other

parts of the kingdom, or from the work of an

ordinary kind done abroad. It is worth noticing,

however, that we find, even in these early Irish

examples, a tendency to vary the monotony of

colour by the introduction of a splashing of black

on the calf covers, the subsequent and more

ambitious development of which produced such

fine effects of harmony in colour as are to be seen

in the intricate and luxurious mosaic designs of

later years. A very striking contrast to the earlier

work is presented in the binding of the House

of Commons’ Journal for the year 1707—the

result, no doubt, of a new appointment which is

known to have been then made to the office of

binder serving that House—and with this volume

begins, and at a high level too, this most remarkable

series of bindings, which, reaching its zenith in the

middle of the eighteenth Century, returned, by

distinctly marked gradations, about the year 1800,.

to even a lower Standard of art and technique than

that from which it started—lower at any rate than

it should have been, having regard to the many

brilliant examples of really admirable work which

then existed in the country. The binders of

almost all these volumes were the firms or

individuals who from time to time held the office

of King’s Stationer, or King’s Printer in Ireiand.

Both offices were granted by Patent—the rights

uncler which were jealously guarded by the

patentees, as the profits derived from the supply of

what was termed “ Stationery Wares” to Parlia-

ment and the Government departments were,

generally speaking, extremely large. The profit

on the actual binding of the Journals, however,

must have been small, for it is known that even

the most elaborately ornamented of them were

charged for at the rate of £6 a volume. The

finest work seems to have been done after the

appointment of Abraham Bradley as King’s

Stationer in 1749. Of the names of the actual

handicraftsmen by whom the designing and tooling

were done, nothing can now be known. There is

not a single volume in the whole set that contains.

the “etiquette” of either firm, or individual, in

any way responsible for the doing of the work.

They all seemed content to labour for art’s sake,

without any thought of advertising or perpetuating

theii names. The volumes of the Journals illus-

trated here are mostly from the later part of the

eighteenth Century. That which is reproduced

on page 54, the Commons Journal, 1765-66, was

probably bound in 1767, and is the work of

Abraham Bradley, the then King’s Stationer.

It is by no means easy to say from what quarter

the Irish binders, when at their best, drew their

inspiration as designers of ornate work. Occasional

traces may be seen of Scotch influences, as for

instance in such an example as the Commons.

57