IV. Graham Robertson

the fact remains that the highest art can as often

be inspired by art as by nature. It is conceivable

that music may lead a poet deeper into the way

of dreams than nature. Listening to it he can

hear the sea and the wind. So old songs may

well give the artist grace to remember beautiful

things in the old world, or to see modern things

in the glamour of old association.

That criticism which takes the line which we

may well call artistic positivism requests that an

artist sball not concern himself with old things.

But why limit art ? Certain Creations do come best

under the pressure of realism: outward things

touching the artist’s senses acutely show him that

which he cannot otherwise know; yet though he

lose these qualities, the artist who says he will

picture only those places which his imagination has

peopled because they are the only places that have

a part in him, is right in seeking for every side of

himself artistic expression.

Mr. Robertson’s art touches another point in his

sympathy with children. In nothing more than its

deference towards the thoughts of children is the

present age characterised. A tenderness which

finds mystic expression in art, and that has no part

in sentimentality, represents as distinctly one phase

of modern art and literature as the poetics of an

uninspired martialism represent another. Steven-

son, the author of “ The Golden Age,” and others

were called by the love of beauty to this kind

religion, with its ritual of flowers and its interest in

defenceless things.

Mr. Robertson’s Mask of May Morning is dedi-

cated tothe sovereignty of children, the courtiership

of flowers.

In the illustrations called Flower of the Wind,

Dead Dreams, The Garden of Weeds, we see

the height of Mr. Robertson’s art. He seems in

these to give back to his subjects an inspiration

which he receives only from such subjects. In

Dead Dreams the child’s gesture touches something

perhaps that is of grief that does not belong to

children, and yet the child-spirit reigns, meeting

regrets with the half welcome that childhood ex-

tends to everything that quickens poignant and

momentary feeling. In Flower of the Wind the

incense of imprisoned flowers is thrown upon the

wind, the child has sent her thoughts to the remote

place where the wind goes.

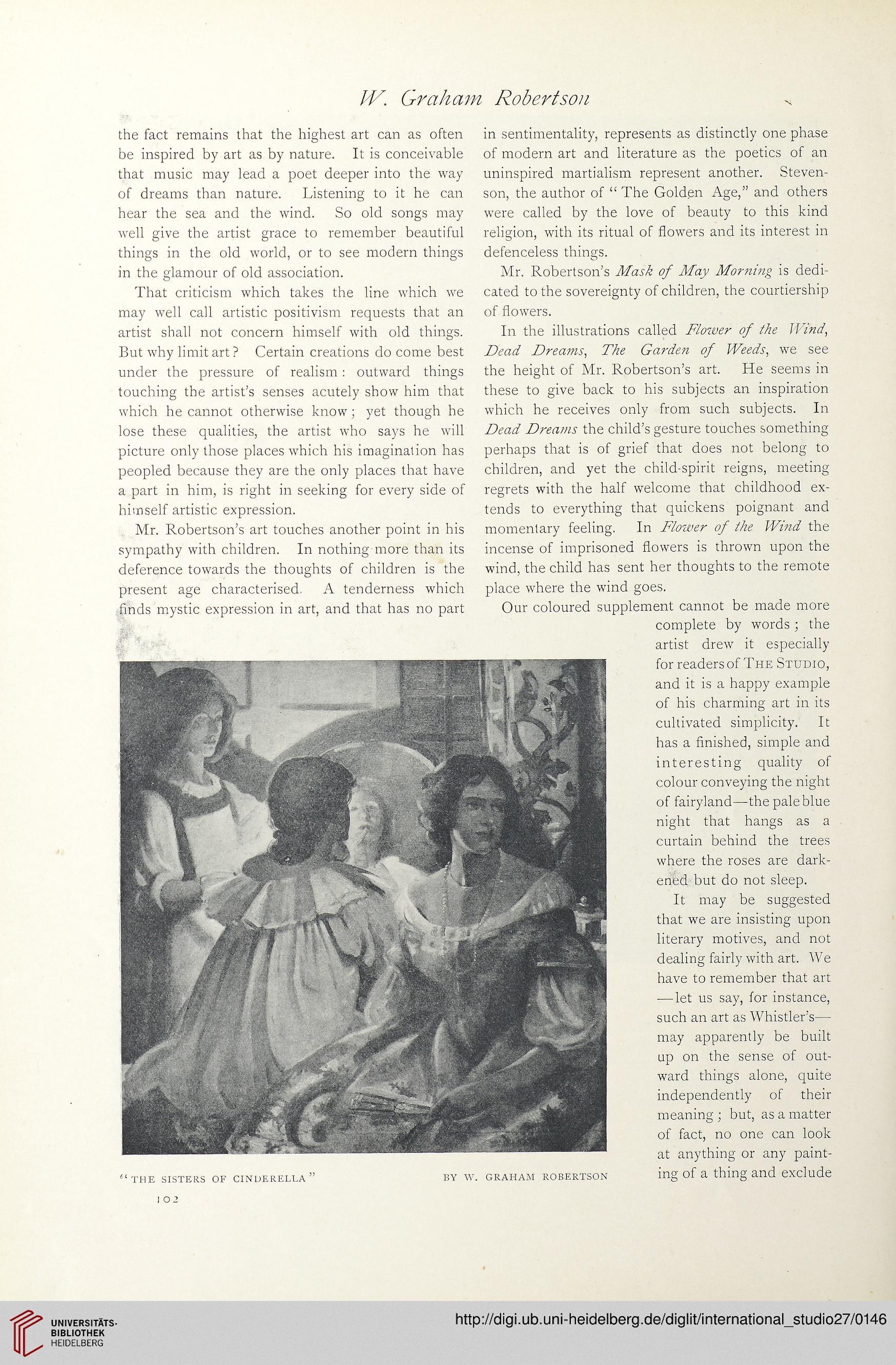

Our coloured Supplement cannot be made more

complete by words ; the

artist drew it especially

for readers of The Studio,

and it is a happy example

of his charming art in its

cultivated simplicity. It

has a finished, simple and

interesting quality of

colour conveying the night

of fairyland—the pale blue

night that hangs as a

curtain behind the trees

where the roses are dark-

ened but do not sleep.

It may be suggested

that we are insisting upon

literary motives, and not

dealing fairly with art. We

have to remember that art

— let us say, for instance,

such an art as Whistler’s—

may apparently be built

up on the sense of out-

ward things alone, quite

independently of their

meaning ; but, as a matter

of fact, no one can look

at anything or any paint-

ing of a thing and exclude

i o 2

the fact remains that the highest art can as often

be inspired by art as by nature. It is conceivable

that music may lead a poet deeper into the way

of dreams than nature. Listening to it he can

hear the sea and the wind. So old songs may

well give the artist grace to remember beautiful

things in the old world, or to see modern things

in the glamour of old association.

That criticism which takes the line which we

may well call artistic positivism requests that an

artist sball not concern himself with old things.

But why limit art ? Certain Creations do come best

under the pressure of realism: outward things

touching the artist’s senses acutely show him that

which he cannot otherwise know; yet though he

lose these qualities, the artist who says he will

picture only those places which his imagination has

peopled because they are the only places that have

a part in him, is right in seeking for every side of

himself artistic expression.

Mr. Robertson’s art touches another point in his

sympathy with children. In nothing more than its

deference towards the thoughts of children is the

present age characterised. A tenderness which

finds mystic expression in art, and that has no part

in sentimentality, represents as distinctly one phase

of modern art and literature as the poetics of an

uninspired martialism represent another. Steven-

son, the author of “ The Golden Age,” and others

were called by the love of beauty to this kind

religion, with its ritual of flowers and its interest in

defenceless things.

Mr. Robertson’s Mask of May Morning is dedi-

cated tothe sovereignty of children, the courtiership

of flowers.

In the illustrations called Flower of the Wind,

Dead Dreams, The Garden of Weeds, we see

the height of Mr. Robertson’s art. He seems in

these to give back to his subjects an inspiration

which he receives only from such subjects. In

Dead Dreams the child’s gesture touches something

perhaps that is of grief that does not belong to

children, and yet the child-spirit reigns, meeting

regrets with the half welcome that childhood ex-

tends to everything that quickens poignant and

momentary feeling. In Flower of the Wind the

incense of imprisoned flowers is thrown upon the

wind, the child has sent her thoughts to the remote

place where the wind goes.

Our coloured Supplement cannot be made more

complete by words ; the

artist drew it especially

for readers of The Studio,

and it is a happy example

of his charming art in its

cultivated simplicity. It

has a finished, simple and

interesting quality of

colour conveying the night

of fairyland—the pale blue

night that hangs as a

curtain behind the trees

where the roses are dark-

ened but do not sleep.

It may be suggested

that we are insisting upon

literary motives, and not

dealing fairly with art. We

have to remember that art

— let us say, for instance,

such an art as Whistler’s—

may apparently be built

up on the sense of out-

ward things alone, quite

independently of their

meaning ; but, as a matter

of fact, no one can look

at anything or any paint-

ing of a thing and exclude

i o 2