Raeburn s

art, would favour the growth of his own. However

that may be, there is apparent in the Chalmers

portrait, and in various others of the pre-Roman

period, a manner quite distinct from that of his

Scottish predecessors and contemporaries. In

place of Ramsay’s soft and well-rounded surfaces

and the feebler brushing of Martin, Raeburn

secures his modelling by means of a simplification

of surfaces to which he has the faculty of reducing

the infinite complexities of nature’s appearances.

This power of generalising is common to all great

artists : that which is personal to Raeburn is the

mosaic-like aspect of the ■work. He deals with

surfaces much as what used to be called drawing

“ on the square ” does with contour. The

advantage of that manner is that through all the

subsequent curvatures by which completion is

sought, something of the simplicity and bigness of

the first enclosing lines remains. In his early

works the fundamental squareness of Raeburn’s

modelling has little of the

fusion which corresponds

to the added curves in the

treatment of contour re-

ferred to. The painter is

feeling his way; the new

method is applied timidly

and with inadequate results

in more ways than one.

The pigment is thin and

starved — there was no

Gandy, as in the case of

Reynolds, to tell the Scot-

tish artist that oil painting

should have a richness of

texture which should re-

mind one of cream or cream

cheese — and the conse-

quent lack of body and

salience is observable well

into his career.

Raeburn achieved noth-

ing very remarkable during

the first ten or twelve years

of his practice. It is not

unlikely that by adopting

the manner then in vogue

success would have come

sooner, but the method

described above had this

advantage: it contained the

germ of almost infinite

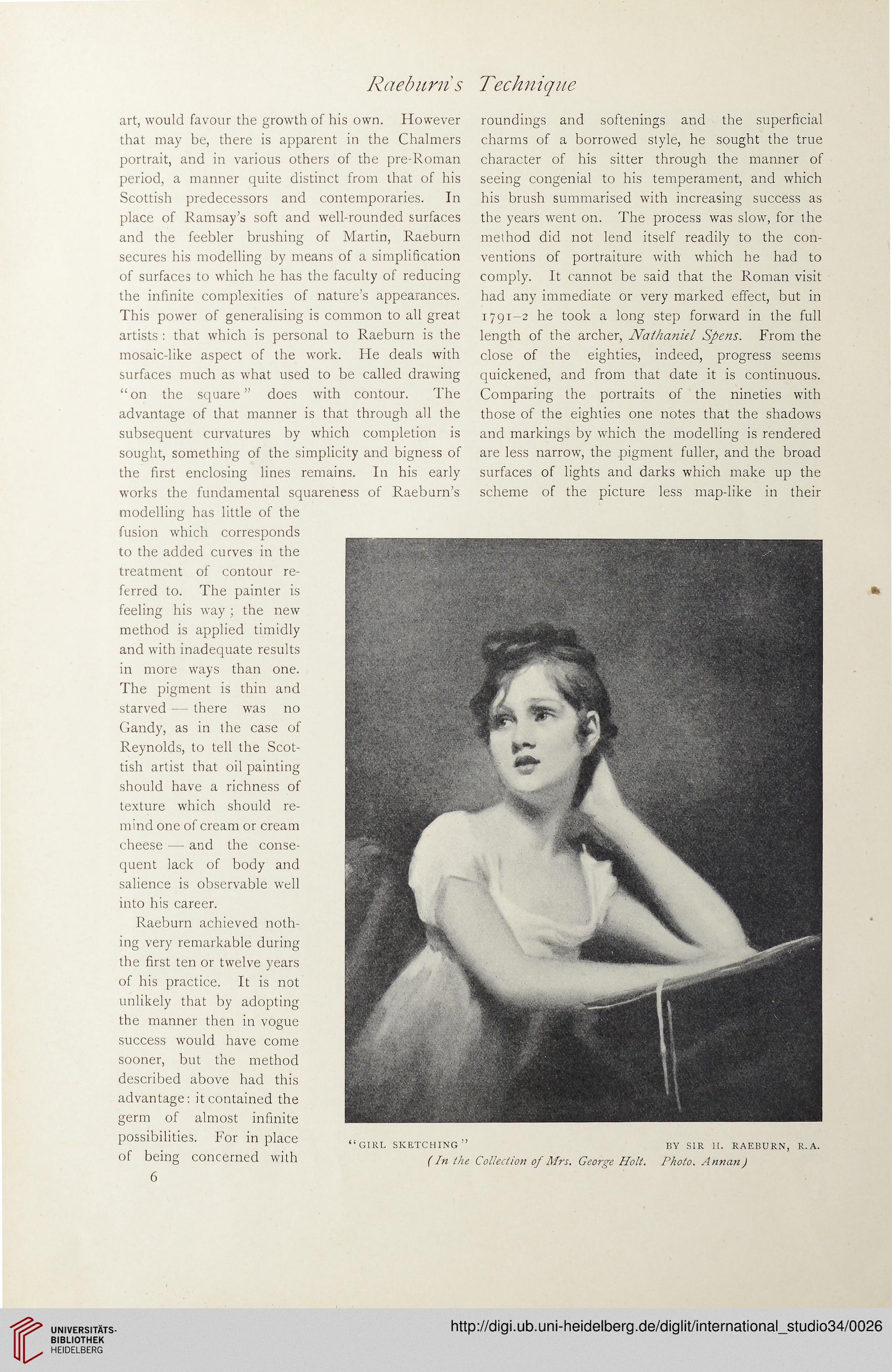

possibilities. For in place

of being concerned with

Technique

roundings and softenings and the superficial

charms of a borrowed style, he sought the true

character of his sitter through the manner of

seeing congenial to his temperament, and which

his brush summarised wfith increasing success as

the years went on. The process was slow, for the

method did not lend itself readily to the con-

ventions of portraiture with which he had to

comply. It cannot be said that the Roman visit

had any immediate or very marked effect, but in

1791-2 he took a long step forward in the full

length of the archer, Nathaniel Spens. From the

close of the eighties, indeed, progress seems

quickened, and from that date it is continuous.

Comparing the portraits of the nineties with

those of the eighties one notes that the shadows

and markings by which the modelling is rendered

are less narrow, the pigment fuller, and the broad

surfaces of lights and darks which make up the

scheme of the picture less map-like in their

art, would favour the growth of his own. However

that may be, there is apparent in the Chalmers

portrait, and in various others of the pre-Roman

period, a manner quite distinct from that of his

Scottish predecessors and contemporaries. In

place of Ramsay’s soft and well-rounded surfaces

and the feebler brushing of Martin, Raeburn

secures his modelling by means of a simplification

of surfaces to which he has the faculty of reducing

the infinite complexities of nature’s appearances.

This power of generalising is common to all great

artists : that which is personal to Raeburn is the

mosaic-like aspect of the ■work. He deals with

surfaces much as what used to be called drawing

“ on the square ” does with contour. The

advantage of that manner is that through all the

subsequent curvatures by which completion is

sought, something of the simplicity and bigness of

the first enclosing lines remains. In his early

works the fundamental squareness of Raeburn’s

modelling has little of the

fusion which corresponds

to the added curves in the

treatment of contour re-

ferred to. The painter is

feeling his way; the new

method is applied timidly

and with inadequate results

in more ways than one.

The pigment is thin and

starved — there was no

Gandy, as in the case of

Reynolds, to tell the Scot-

tish artist that oil painting

should have a richness of

texture which should re-

mind one of cream or cream

cheese — and the conse-

quent lack of body and

salience is observable well

into his career.

Raeburn achieved noth-

ing very remarkable during

the first ten or twelve years

of his practice. It is not

unlikely that by adopting

the manner then in vogue

success would have come

sooner, but the method

described above had this

advantage: it contained the

germ of almost infinite

possibilities. For in place

of being concerned with

Technique

roundings and softenings and the superficial

charms of a borrowed style, he sought the true

character of his sitter through the manner of

seeing congenial to his temperament, and which

his brush summarised wfith increasing success as

the years went on. The process was slow, for the

method did not lend itself readily to the con-

ventions of portraiture with which he had to

comply. It cannot be said that the Roman visit

had any immediate or very marked effect, but in

1791-2 he took a long step forward in the full

length of the archer, Nathaniel Spens. From the

close of the eighties, indeed, progress seems

quickened, and from that date it is continuous.

Comparing the portraits of the nineties with

those of the eighties one notes that the shadows

and markings by which the modelling is rendered

are less narrow, the pigment fuller, and the broad

surfaces of lights and darks which make up the

scheme of the picture less map-like in their