Homer Martin, American Landscape Painter

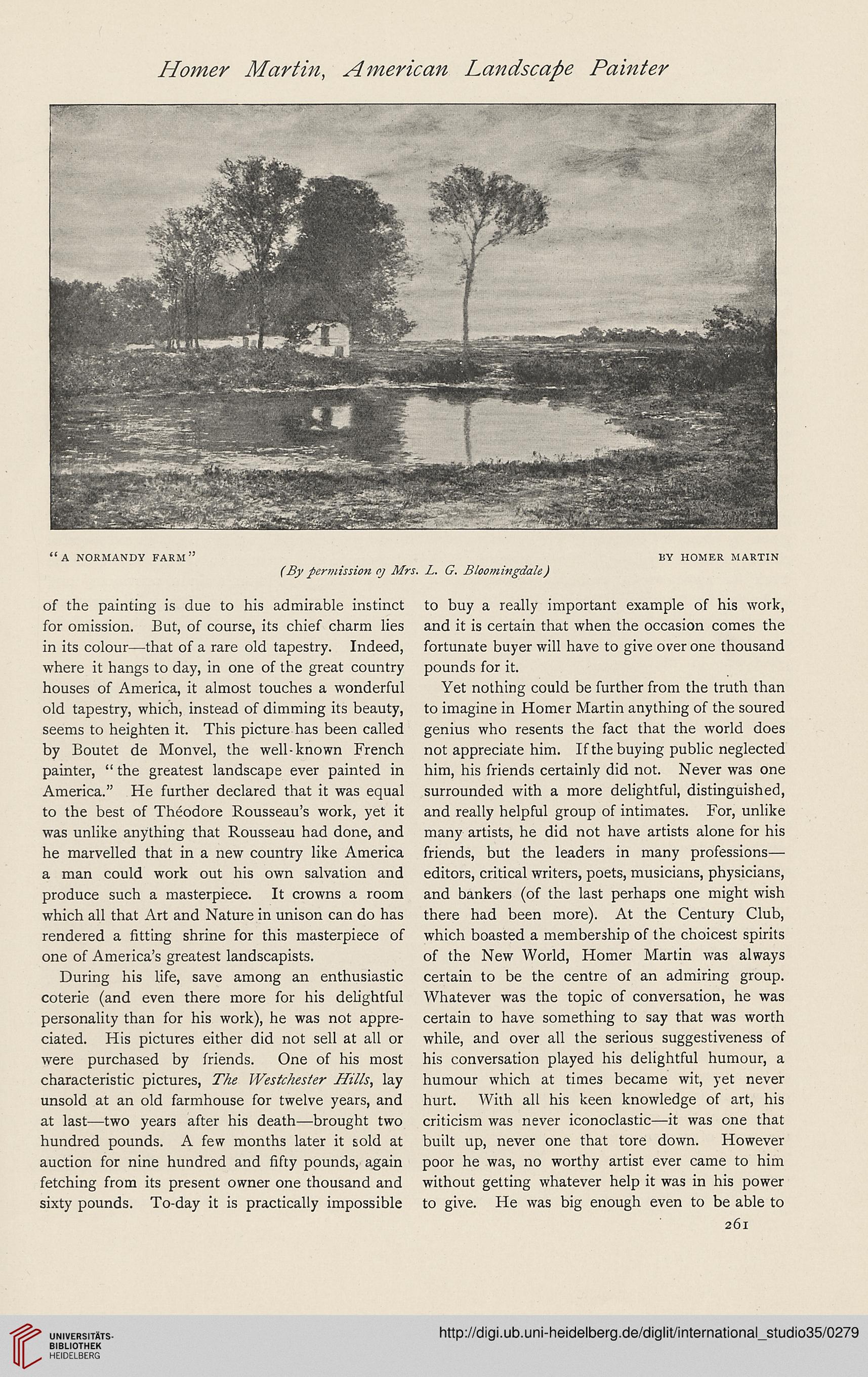

“A NORMANDY FARM” BY HOMER MARTIN

(By permission oj Mrs. L. G. Bloomingdah)

of the painting is due to his admirable instinct

for omission. But, of course, its chief charm lies

in its colour—that of a rare old tapestry. Indeed,

where it hangs to day, in one of the great country

houses of America, it almost touches a wonderful

old tapestry, which, instead of dimming its beauty,

seems to heighten it. This picture has been called

by Boutet de Monvel, the well-known French

painter, “ the greatest landscape ever painted in

America.” He further declared that it was equal

to the best of Theodore Rousseau’s work, yet it

was unlike anything that Rousseau had done, and

he marvelled that in a new country like America

a man could work out his own salvation and

produce such a masterpiece. It crowns a room

which all that Art and Nature in unison can do has

rendered a fitting shrine for this masterpiece of

one of America’s greatest landscapists.

During his life, save among an enthusiastic

coterie (and even there more for his delightful

personality than for his work), he was not appre-

ciated. His pictures either did not sell at all or

were purchased by friends. One of his most

characteristic pictures, The Westchester Hills, lay

unsold at an old farmhouse for twelve years, and

at last—two years after his death—brought two

hundred pounds. A few months later it sold at

auction for nine hundred and fifty pounds, again

fetching from its present owner one thousand and

sixty pounds. To-day it is practically impossible

to buy a really important example of his work,

and it is certain that when the occasion comes the

fortunate buyer will have to give over one thousand

pounds for it.

Yet nothing could be further from the truth than

to imagine in Homer Martin anything of the soured

genius who resents the fact that the world does

not appreciate him. If the buying public neglected

him, his friends certainly did not. Never was one

surrounded with a more delightful, distinguished,

and really helpful group of intimates. For, unlike

many artists, he did not have artists alone for his

friends, but the leaders in many professions—

editors, critical writers, poets, musicians, physicians,

and bankers (of the last perhaps one might wish

there had been more). At the Century Club,

which boasted a membership of the choicest spirits

of the New World, Homer Martin was always

certain to be the centre of an admiring group.

Whatever was the topic of conversation, he was

certain to have something to say that was worth

while, and over all the serious suggestiveness of

his conversation played his delightful humour, a

humour which at times became wit, yet never

hurt. With all his keen knowledge of art, his

criticism was never iconoclastic—it was one that

built up, never one that tore down. However

poor he was, no worthy artist ever came to him

without getting whatever help it was in his power

to give. He was big enough even to be able to

261

“A NORMANDY FARM” BY HOMER MARTIN

(By permission oj Mrs. L. G. Bloomingdah)

of the painting is due to his admirable instinct

for omission. But, of course, its chief charm lies

in its colour—that of a rare old tapestry. Indeed,

where it hangs to day, in one of the great country

houses of America, it almost touches a wonderful

old tapestry, which, instead of dimming its beauty,

seems to heighten it. This picture has been called

by Boutet de Monvel, the well-known French

painter, “ the greatest landscape ever painted in

America.” He further declared that it was equal

to the best of Theodore Rousseau’s work, yet it

was unlike anything that Rousseau had done, and

he marvelled that in a new country like America

a man could work out his own salvation and

produce such a masterpiece. It crowns a room

which all that Art and Nature in unison can do has

rendered a fitting shrine for this masterpiece of

one of America’s greatest landscapists.

During his life, save among an enthusiastic

coterie (and even there more for his delightful

personality than for his work), he was not appre-

ciated. His pictures either did not sell at all or

were purchased by friends. One of his most

characteristic pictures, The Westchester Hills, lay

unsold at an old farmhouse for twelve years, and

at last—two years after his death—brought two

hundred pounds. A few months later it sold at

auction for nine hundred and fifty pounds, again

fetching from its present owner one thousand and

sixty pounds. To-day it is practically impossible

to buy a really important example of his work,

and it is certain that when the occasion comes the

fortunate buyer will have to give over one thousand

pounds for it.

Yet nothing could be further from the truth than

to imagine in Homer Martin anything of the soured

genius who resents the fact that the world does

not appreciate him. If the buying public neglected

him, his friends certainly did not. Never was one

surrounded with a more delightful, distinguished,

and really helpful group of intimates. For, unlike

many artists, he did not have artists alone for his

friends, but the leaders in many professions—

editors, critical writers, poets, musicians, physicians,

and bankers (of the last perhaps one might wish

there had been more). At the Century Club,

which boasted a membership of the choicest spirits

of the New World, Homer Martin was always

certain to be the centre of an admiring group.

Whatever was the topic of conversation, he was

certain to have something to say that was worth

while, and over all the serious suggestiveness of

his conversation played his delightful humour, a

humour which at times became wit, yet never

hurt. With all his keen knowledge of art, his

criticism was never iconoclastic—it was one that

built up, never one that tore down. However

poor he was, no worthy artist ever came to him

without getting whatever help it was in his power

to give. He was big enough even to be able to

261