Modern German Embroidery

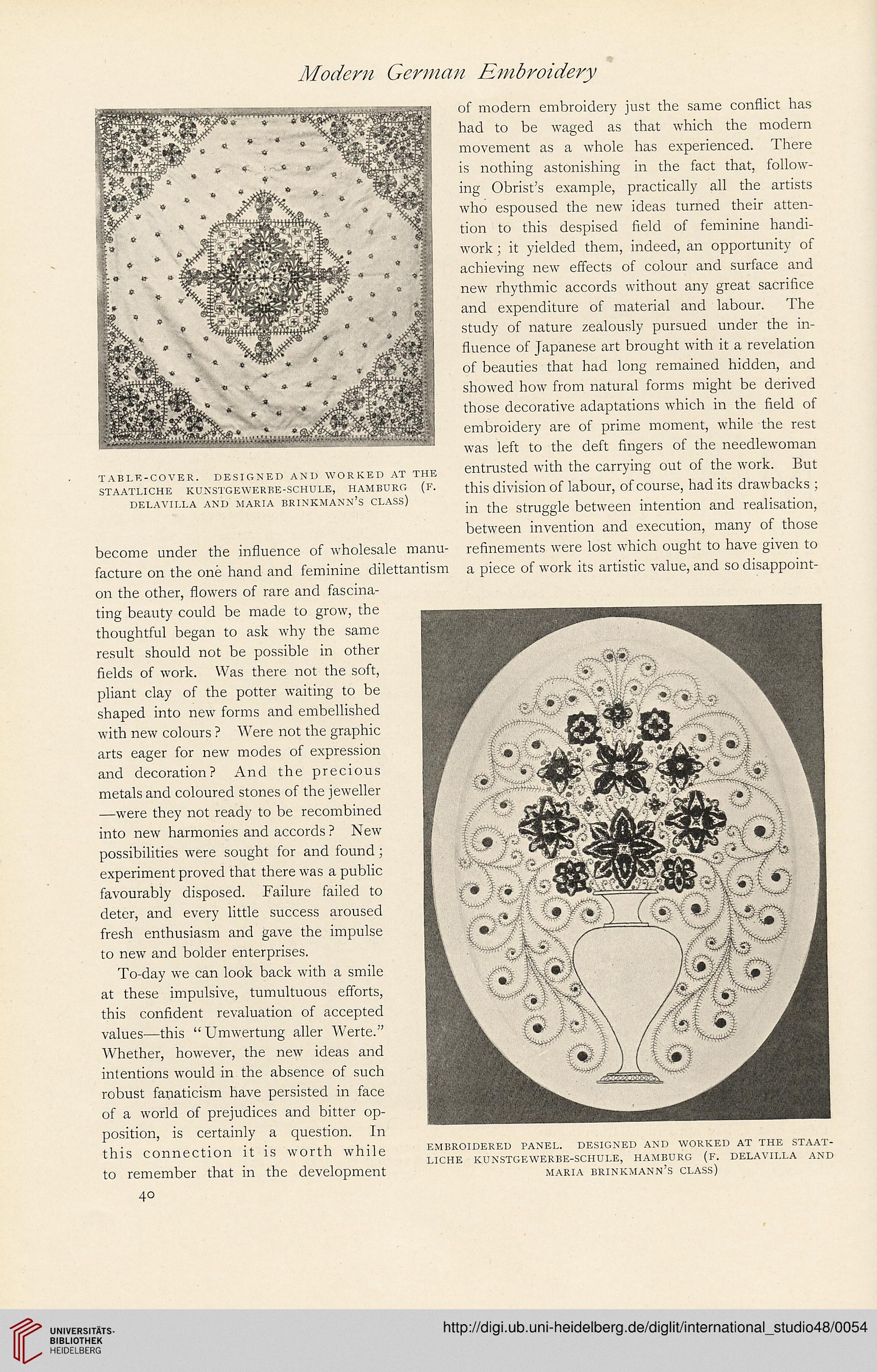

TABLE-COVER. DESIGNED AND WORKED AT THE

STAATLICHE KUNSTGEWERBE-SCHULE, HAMBURG (F.

DELAVII.LA AND MARIA BRINKMANN’S CLASS)

become under the influence of wholesale manu-

facture on the one hand and feminine dilettantism

on the other, flowers of rare and fascina-

of modern embroidery just the same conflict has

had to be waged as that which the modern

movement as a whole has experienced. There

is nothing astonishing in the fact that, follow-

ing Obrist’s example, practically all the artists

who espoused the new ideas turned their atten-

tion to this despised field of feminine handi-

work ; it yielded them, indeed, an opportunity of

achieving new effects of colour and surface and

new rhythmic accords without any great sacrifice

and expenditure of material and labour. The

study of nature zealously pursued under the in-

fluence of Japanese art brought with it a revelation

of beauties that had long remained hidden, and

showed how from natural forms might be derived

those decorative adaptations which in the field of

embroidery are of prime moment, while the rest

was left to the deft fingers of the needlewoman

entrusted with the carrying out of the work. But

this division of labour, of course, had its drawbacks ;

in the struggle between intention and realisation,

between invention and execution, many of those

refinements were lost which ought to have given to

a piece of work its artistic value, and so disappoint-

ting beauty could be made to grow, the

thoughtful began to ask why the same

result should not be possible in other

fields of work. Was there not the soft,

pliant clay of the potter waiting to be

shaped into new forms and embellished

with new colours ? Were not the graphic

arts eager for new modes of expression

and decoration? And the precious

metals and coloured stones of the jeweller

—were they not ready to be recombined

into new harmonies and accords ? New

possibilities were sought for and found;

experiment proved that there was a public

favourably disposed. Failure failed to

deter, and every little success aroused

fresh enthusiasm and gave the impulse

to new and bolder enterprises.

To-day we can look back with a smile

at these impulsive, tumultuous efforts,

this confident revaluation of accepted

values—this “ Umwertung aller Werte.”

Whether, however, the new ideas and

intentions would in the absence of such

robust fanaticism have persisted in face

of a world of prejudices and bitter op-

position, is certainly a question. In

this connection it is worth while

to remember that in the development

EMBROIDERED PANEL. DESIGNED AND WORKED AT THE STAAT-

LICHE KUNSTGEWERBE-SCHULE, HAMBURG (F. DELAVII.LA AND

MARIA BRINKMANN’S CLASS)

40

TABLE-COVER. DESIGNED AND WORKED AT THE

STAATLICHE KUNSTGEWERBE-SCHULE, HAMBURG (F.

DELAVII.LA AND MARIA BRINKMANN’S CLASS)

become under the influence of wholesale manu-

facture on the one hand and feminine dilettantism

on the other, flowers of rare and fascina-

of modern embroidery just the same conflict has

had to be waged as that which the modern

movement as a whole has experienced. There

is nothing astonishing in the fact that, follow-

ing Obrist’s example, practically all the artists

who espoused the new ideas turned their atten-

tion to this despised field of feminine handi-

work ; it yielded them, indeed, an opportunity of

achieving new effects of colour and surface and

new rhythmic accords without any great sacrifice

and expenditure of material and labour. The

study of nature zealously pursued under the in-

fluence of Japanese art brought with it a revelation

of beauties that had long remained hidden, and

showed how from natural forms might be derived

those decorative adaptations which in the field of

embroidery are of prime moment, while the rest

was left to the deft fingers of the needlewoman

entrusted with the carrying out of the work. But

this division of labour, of course, had its drawbacks ;

in the struggle between intention and realisation,

between invention and execution, many of those

refinements were lost which ought to have given to

a piece of work its artistic value, and so disappoint-

ting beauty could be made to grow, the

thoughtful began to ask why the same

result should not be possible in other

fields of work. Was there not the soft,

pliant clay of the potter waiting to be

shaped into new forms and embellished

with new colours ? Were not the graphic

arts eager for new modes of expression

and decoration? And the precious

metals and coloured stones of the jeweller

—were they not ready to be recombined

into new harmonies and accords ? New

possibilities were sought for and found;

experiment proved that there was a public

favourably disposed. Failure failed to

deter, and every little success aroused

fresh enthusiasm and gave the impulse

to new and bolder enterprises.

To-day we can look back with a smile

at these impulsive, tumultuous efforts,

this confident revaluation of accepted

values—this “ Umwertung aller Werte.”

Whether, however, the new ideas and

intentions would in the absence of such

robust fanaticism have persisted in face

of a world of prejudices and bitter op-

position, is certainly a question. In

this connection it is worth while

to remember that in the development

EMBROIDERED PANEL. DESIGNED AND WORKED AT THE STAAT-

LICHE KUNSTGEWERBE-SCHULE, HAMBURG (F. DELAVII.LA AND

MARIA BRINKMANN’S CLASS)

40