Anders Zorn

brought himself into prominence at the close of

the eighteen eighties. And he has gained new

laurels on the old well-known field. He has

probably hardly ever painted anything more

delicate than Sjoblom's Scow ; Dagmar has been

imagined mainly as a tone of soft, northern blond-

every line of his brush, in every play of sunlight

and each wrinkle on her face. In Sunday, both

the model and the stamning, or mood, are

different. Here we have a herd-girl, who, alone in

her shealing high up among the fells, has dressed

herself in her whitest shift and the best skirt she

ness, while Startled — a

has at hand, and hears the

picture of this year showing

three young women run-

ning towards the water

—must perhaps be ac-

counted, from an artistic

point of view, the richest

in conception, with its de-

lineation of that typically

Swedish, obliquely trun-

cated shore-motif which

has so often served as the

frame of his paintings of

the nude. What is most

worthy of our admiration

in these things is the

manner in which the

atmosphere melts, as it

were, into human figure

and the landscape, and the

natural, innate freedom of

the movements. Simply

astounding in the last-

named picture is the way

in which the artist has

caught and reproduced in

his canvas the light, un-

constrained movement of

the startled women in their

hurry to seek shelter, and

their careful stepping over

the pine-needles that cover

the slippery rocks. From

a psychological point of

view this rendering of

movement is absolutely

convincing.

That feeling of subtilised

French technique which

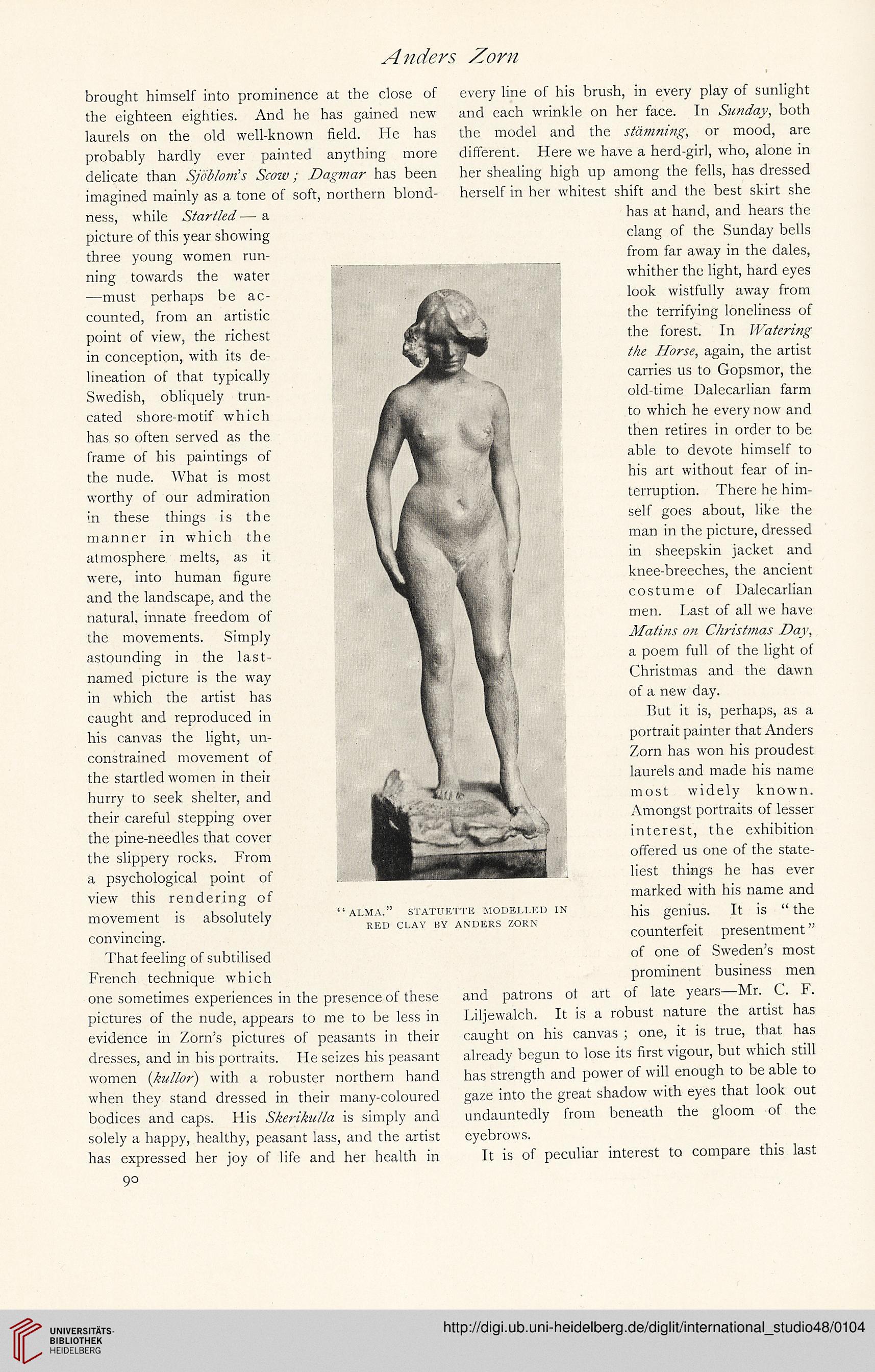

“ALMA.” STATUETTE MODELLED IN

RED CLAY BY ANDERS ZORN

clang of the Sunday bells

from far away in the dales,

whither the light, hard eyes

look wistfully away from

the terrifying loneliness of

the forest. In Watering

the Horse, again, the artist

carries us to Gopsmor, the

old-time Dalecarlian farm

to which he every now and

then retires in order to be

able to devote himself to

his art without fear of in-

terruption. There he him-

self goes about, like the

man in the picture, dressed

in sheepskin jacket and

knee-breeches, the ancient

costume of Dalecarlian

men. Last of all we have

Matins on Christmas Day,

a poem full of the light of

Christmas and the dawn

of a new day.

But it is, perhaps, as a

portrait painter that Anders

Zorn has won his proudest

laurels and made his name

most widely known.

Amongst portraits of lesser

interest, the exhibition

offered us one of the state-

liest things he has ever

marked with his name and

his genius. It is “ the

counterfeit presentment ”

of one of Sweden’s most

prominent business men

one sometimes experiences in the presence of these

pictures of the nude, appears to me to be less in

evidence in Zorn’s pictures of peasants in their

dresses, and in his portraits. He seizes his peasant

women (kullor) with a robuster northern hand

when they stand dressed in their many-coloured

bodices and caps. His Skerikulla is simply and

solely a happy, healthy, peasant lass, and the artist

has expressed her joy of life and her health in

and patrons ot art of late years—Mr. C. F.

Liljewalch. It is a robust nature the artist has

caught on his canvas ; one, it is true, that has

already begun to lose its first vigour, but which still

has strength and power of will enough to be able to

gaze into the great shadow with eyes that look out

undauntedly from beneath the gloom of the

eyebrows.

It is of peculiar interest to compare this last

9°

brought himself into prominence at the close of

the eighteen eighties. And he has gained new

laurels on the old well-known field. He has

probably hardly ever painted anything more

delicate than Sjoblom's Scow ; Dagmar has been

imagined mainly as a tone of soft, northern blond-

every line of his brush, in every play of sunlight

and each wrinkle on her face. In Sunday, both

the model and the stamning, or mood, are

different. Here we have a herd-girl, who, alone in

her shealing high up among the fells, has dressed

herself in her whitest shift and the best skirt she

ness, while Startled — a

has at hand, and hears the

picture of this year showing

three young women run-

ning towards the water

—must perhaps be ac-

counted, from an artistic

point of view, the richest

in conception, with its de-

lineation of that typically

Swedish, obliquely trun-

cated shore-motif which

has so often served as the

frame of his paintings of

the nude. What is most

worthy of our admiration

in these things is the

manner in which the

atmosphere melts, as it

were, into human figure

and the landscape, and the

natural, innate freedom of

the movements. Simply

astounding in the last-

named picture is the way

in which the artist has

caught and reproduced in

his canvas the light, un-

constrained movement of

the startled women in their

hurry to seek shelter, and

their careful stepping over

the pine-needles that cover

the slippery rocks. From

a psychological point of

view this rendering of

movement is absolutely

convincing.

That feeling of subtilised

French technique which

“ALMA.” STATUETTE MODELLED IN

RED CLAY BY ANDERS ZORN

clang of the Sunday bells

from far away in the dales,

whither the light, hard eyes

look wistfully away from

the terrifying loneliness of

the forest. In Watering

the Horse, again, the artist

carries us to Gopsmor, the

old-time Dalecarlian farm

to which he every now and

then retires in order to be

able to devote himself to

his art without fear of in-

terruption. There he him-

self goes about, like the

man in the picture, dressed

in sheepskin jacket and

knee-breeches, the ancient

costume of Dalecarlian

men. Last of all we have

Matins on Christmas Day,

a poem full of the light of

Christmas and the dawn

of a new day.

But it is, perhaps, as a

portrait painter that Anders

Zorn has won his proudest

laurels and made his name

most widely known.

Amongst portraits of lesser

interest, the exhibition

offered us one of the state-

liest things he has ever

marked with his name and

his genius. It is “ the

counterfeit presentment ”

of one of Sweden’s most

prominent business men

one sometimes experiences in the presence of these

pictures of the nude, appears to me to be less in

evidence in Zorn’s pictures of peasants in their

dresses, and in his portraits. He seizes his peasant

women (kullor) with a robuster northern hand

when they stand dressed in their many-coloured

bodices and caps. His Skerikulla is simply and

solely a happy, healthy, peasant lass, and the artist

has expressed her joy of life and her health in

and patrons ot art of late years—Mr. C. F.

Liljewalch. It is a robust nature the artist has

caught on his canvas ; one, it is true, that has

already begun to lose its first vigour, but which still

has strength and power of will enough to be able to

gaze into the great shadow with eyes that look out

undauntedly from beneath the gloom of the

eyebrows.

It is of peculiar interest to compare this last

9°