Studio-Talk

He lives isolated, aloof even from contemporary

artistic movements. A Castilian, deeply attached

to his country, he has transcribed that attachment

in some magnificent pictures depicting the customs

of Castile; poet, he gives free rein to his poesy in

certain fine decorative works; and lastly, as a painter

in the true sense of the word, as a lover of colour,

he delights also in studies of light, impressions of

movement and in various “effects.”

Chicharro does not paint the peasants of Castile

because they are picturesque, but because he finds

himself in the closest affinity with them, because

their past is his own and because the soil over

which they bow themselves and from which they

draw their sustenance, this parched earth which we

see in the background of his pictures, is the soil

of his own fatherland, scorched by his own sun.

All these Castilian works of Chicharro are intimately

realistic; but there is, so to say, an immediate

realism, and there is a second realism infinitely

more lofty than the first, which represents not only

what is seen but what is felt.

After the contemplation of these arid plateaux,

these immense horizons in which there is nothing

to distract or rest the eye,

Chicharro dreams of

another nature where the

vegetation is luxurious and

abundant, where nothing

offends or wearies the eye,

where all the forms are

beautiful not only with a

beauty of character but

also with a beauty of har¬

mony, for he is Latin in

temperament despite all

the appeal of atticism.

From this aspiration to

escape at times from the

all-compelling love of his

own land come no doubt

certain landscapes in his

decorative panels, such as

L' Inspiration, with delicate

tones and numerous con-

tours to arrest the eye.

These stand as the anti-

thesis of his Castilian

pictures in which he is

preoccupied with the verity

of his transcriptions of

nature, and his decorative

panels become thus symbolical works in which

even the central idea is a figment of the artist’s

brain. Here we find him introducing figures, for

he finds them the most apt to reproduce his

thought; but these forms are not there for them-

selves alone—despite their corporeal appearance

they do not exist as human beings, but are present

as manifestations of passions, of eternal ideas of

humanity. Chicharro makes use of no special

mythology but employs the symbolism slowly

created by mankind, symbols of everlasting import

which he feels in himself and which are concordant

with his artistic emotions, and which he re-creates

in himself in the image of his own personality.

Chicharro does not boast of his philosophy, and if

his decorative works are so profoundly philosophical

it is because they are the purest and truest ex-

pression of his artistic sensibilities and thought.

Hence their simplicity of line, hence that emotional

quality which we find in still greater degree in the

sketches which are the first essays towards their

creation. All these panels, even to the mournful

mediaeval triptych Les Trois Epouses, are of the genre

of “ inward ” picturing, of “ thoughtful ” painting.

Chicharro has been described as a “colourist,”

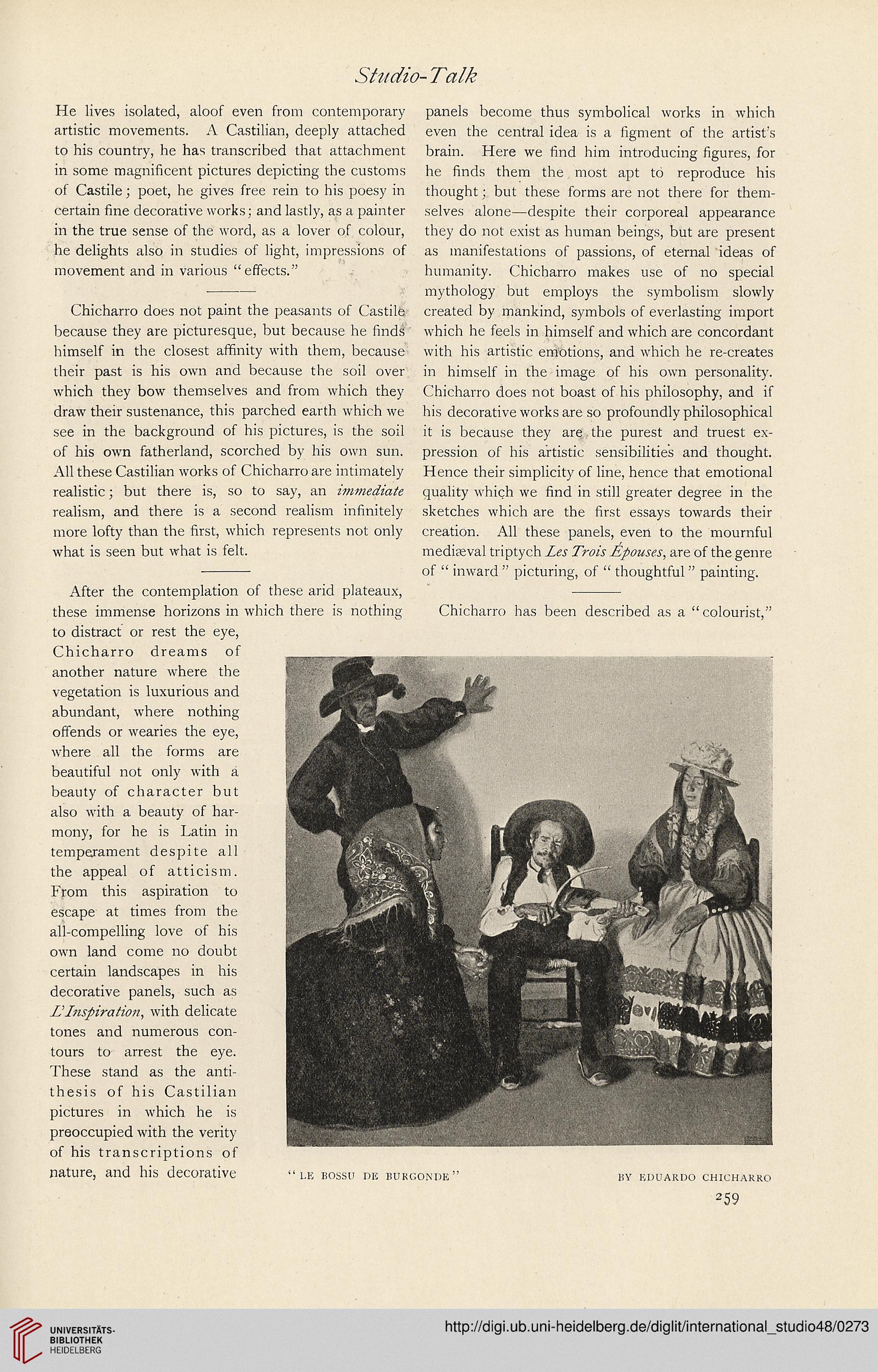

“ LE BOSSU DE BURGONDE”

BY EDUARDO CHICHARRO

259

He lives isolated, aloof even from contemporary

artistic movements. A Castilian, deeply attached

to his country, he has transcribed that attachment

in some magnificent pictures depicting the customs

of Castile; poet, he gives free rein to his poesy in

certain fine decorative works; and lastly, as a painter

in the true sense of the word, as a lover of colour,

he delights also in studies of light, impressions of

movement and in various “effects.”

Chicharro does not paint the peasants of Castile

because they are picturesque, but because he finds

himself in the closest affinity with them, because

their past is his own and because the soil over

which they bow themselves and from which they

draw their sustenance, this parched earth which we

see in the background of his pictures, is the soil

of his own fatherland, scorched by his own sun.

All these Castilian works of Chicharro are intimately

realistic; but there is, so to say, an immediate

realism, and there is a second realism infinitely

more lofty than the first, which represents not only

what is seen but what is felt.

After the contemplation of these arid plateaux,

these immense horizons in which there is nothing

to distract or rest the eye,

Chicharro dreams of

another nature where the

vegetation is luxurious and

abundant, where nothing

offends or wearies the eye,

where all the forms are

beautiful not only with a

beauty of character but

also with a beauty of har¬

mony, for he is Latin in

temperament despite all

the appeal of atticism.

From this aspiration to

escape at times from the

all-compelling love of his

own land come no doubt

certain landscapes in his

decorative panels, such as

L' Inspiration, with delicate

tones and numerous con-

tours to arrest the eye.

These stand as the anti-

thesis of his Castilian

pictures in which he is

preoccupied with the verity

of his transcriptions of

nature, and his decorative

panels become thus symbolical works in which

even the central idea is a figment of the artist’s

brain. Here we find him introducing figures, for

he finds them the most apt to reproduce his

thought; but these forms are not there for them-

selves alone—despite their corporeal appearance

they do not exist as human beings, but are present

as manifestations of passions, of eternal ideas of

humanity. Chicharro makes use of no special

mythology but employs the symbolism slowly

created by mankind, symbols of everlasting import

which he feels in himself and which are concordant

with his artistic emotions, and which he re-creates

in himself in the image of his own personality.

Chicharro does not boast of his philosophy, and if

his decorative works are so profoundly philosophical

it is because they are the purest and truest ex-

pression of his artistic sensibilities and thought.

Hence their simplicity of line, hence that emotional

quality which we find in still greater degree in the

sketches which are the first essays towards their

creation. All these panels, even to the mournful

mediaeval triptych Les Trois Epouses, are of the genre

of “ inward ” picturing, of “ thoughtful ” painting.

Chicharro has been described as a “colourist,”

“ LE BOSSU DE BURGONDE”

BY EDUARDO CHICHARRO

259