W. Elmer Schofield

with Metcalf and Redfield, to mention but two

others, became the founders of an American school

of landscape, rooted and grounded in the soil, and

expressing broadly and simply the rolling spacious-

ness and clear atmosphere of their land. I re-

member a few years ago at an exhibition of the

Pennsylvania Academy a series of landscapes by

Schofield, Metcalf, and Redfield. They have left

a memory of spaciousness, of an open, unsophisti-

cated landscape-land, with great rivers and thin

sky-stretching trees, nature seen expansively, the

pigment laid on in broad, simple strokes, the figure

rarely or never introduced, nature as she is viewed

by steady eyes, Paris trained, but remaining in-

herently amd essentially American.

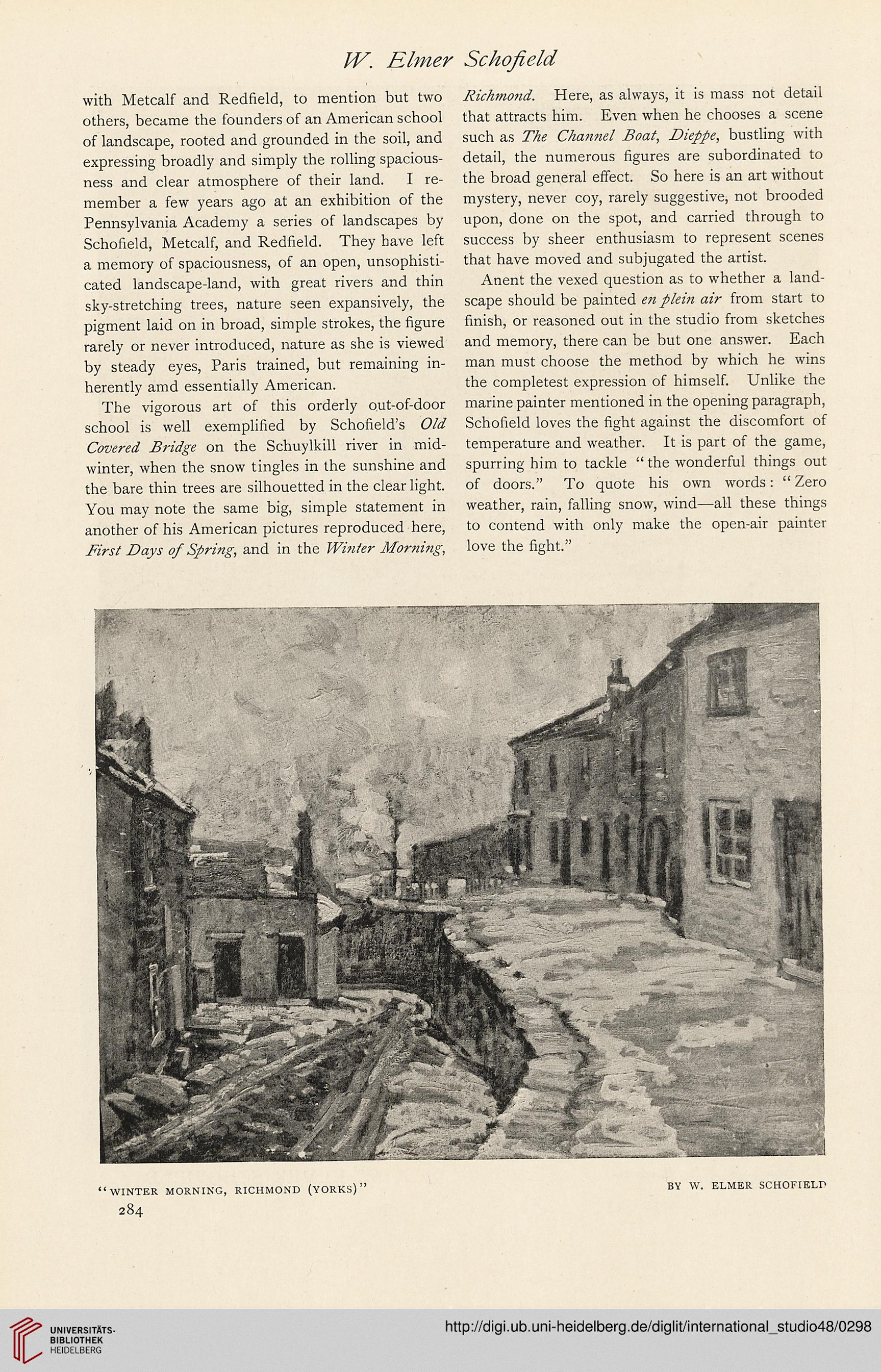

The vigorous art of this orderly out-of-door

school is well exemplified by Schofield’s Old

Covered Bridge on the Schuylkill river in mid-

winter, when the snow tingles in the sunshine and

the bare thin trees are silhouetted in the clear light.

You may note the same big, simple statement in

another of his American pictures reproduced here,

First Days of Spring, and in the Winter Morning,

Richmond. Here, as always, it is mass not detail

that attracts him. Even when he chooses a scene

such as The Channel Boat, Dieppe, bustling with

detail, the numerous figures are subordinated to

the broad general effect. So here is an art without

mystery, never coy, rarely suggestive, not brooded

upon, done on the spot, and carried through to

success by sheer enthusiasm to represent scenes

that have moved and subjugated the artist.

Anent the vexed question as to whether a land-

scape should be painted en plein air from start to

finish, or reasoned out in the studio from sketches

and memory, there can be but one answer. Each

man must choose the method by which he wins

the completest expression of himself. Unlike the

marine painter mentioned in the opening paragraph,

Schofield loves the fight against the discomfort of

temperature and weather. It is part of the game,

spurring him to tackle “ the wonderful things out

of doors.” To quote his own words: “ Zero

weather, rain, falling snow, wind—all these things

to contend with only make the open-air painter

love the fight.”

“WINTER MORNING, RICHMOND (YORKS)”

284

BY W. ELMER SCHOFIELD

with Metcalf and Redfield, to mention but two

others, became the founders of an American school

of landscape, rooted and grounded in the soil, and

expressing broadly and simply the rolling spacious-

ness and clear atmosphere of their land. I re-

member a few years ago at an exhibition of the

Pennsylvania Academy a series of landscapes by

Schofield, Metcalf, and Redfield. They have left

a memory of spaciousness, of an open, unsophisti-

cated landscape-land, with great rivers and thin

sky-stretching trees, nature seen expansively, the

pigment laid on in broad, simple strokes, the figure

rarely or never introduced, nature as she is viewed

by steady eyes, Paris trained, but remaining in-

herently amd essentially American.

The vigorous art of this orderly out-of-door

school is well exemplified by Schofield’s Old

Covered Bridge on the Schuylkill river in mid-

winter, when the snow tingles in the sunshine and

the bare thin trees are silhouetted in the clear light.

You may note the same big, simple statement in

another of his American pictures reproduced here,

First Days of Spring, and in the Winter Morning,

Richmond. Here, as always, it is mass not detail

that attracts him. Even when he chooses a scene

such as The Channel Boat, Dieppe, bustling with

detail, the numerous figures are subordinated to

the broad general effect. So here is an art without

mystery, never coy, rarely suggestive, not brooded

upon, done on the spot, and carried through to

success by sheer enthusiasm to represent scenes

that have moved and subjugated the artist.

Anent the vexed question as to whether a land-

scape should be painted en plein air from start to

finish, or reasoned out in the studio from sketches

and memory, there can be but one answer. Each

man must choose the method by which he wins

the completest expression of himself. Unlike the

marine painter mentioned in the opening paragraph,

Schofield loves the fight against the discomfort of

temperature and weather. It is part of the game,

spurring him to tackle “ the wonderful things out

of doors.” To quote his own words: “ Zero

weather, rain, falling snow, wind—all these things

to contend with only make the open-air painter

love the fight.”

“WINTER MORNING, RICHMOND (YORKS)”

284

BY W. ELMER SCHOFIELD