The House Beautiful of Japan

Courtesy of Yamanaka &• Company

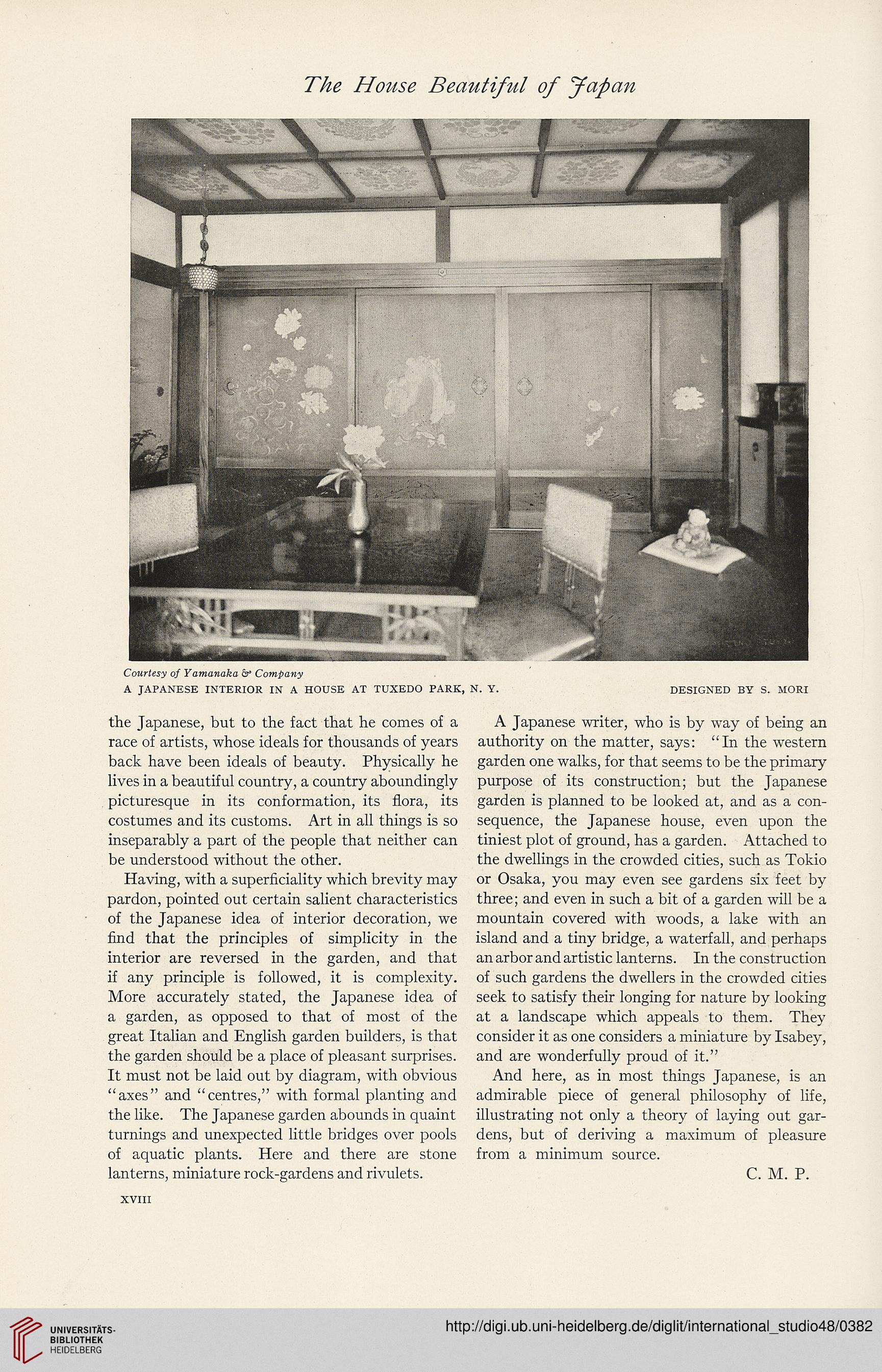

A JAPANESE INTERIOR IN A HOUSE AT TUXEDO PARK, N. Y. DESIGNED BY S. MORI

the Japanese, but to the fact that he comes of a

race of artists, whose ideals for thousands of years

back have been ideals of beauty. Physically he

lives in a beautiful country, a country aboundingly

picturesque in its conformation, its flora, its

costumes and its customs. Art in all things is so

inseparably a part of the people that neither can

be understood without the other.

Having, with a superficiality which brevity may

pardon, pointed out certain salient characteristics

of the Japanese idea of interior decoration, we

find that the principles of simplicity in the

interior are reversed in the garden, and that

if any principle is followed, it is complexity.

More accurately stated, the Japanese idea of

a garden, as opposed to that of most of the

great Italian and English garden builders, is that

the garden should be a place of pleasant surprises.

It must not be laid out by diagram, with obvious

“axes” and “centres,” with formal planting and

the like. The Japanese garden abounds in quaint

turnings and unexpected little bridges over pools

of aquatic plants. Here and there are stone

lanterns, miniature rock-gardens and rivulets.

A Japanese writer, who is by way of being an

authority on the matter, says: “In the western

garden one walks, for that seems to be the primary

purpose of its construction; but the Japanese

garden is planned to be looked at, and as a con-

sequence, the Japanese house, even upon the

tiniest plot of ground, has a garden. Attached to

the dwellings in the crowded cities, such as Tokio

or Osaka, you may even see gardens six feet by

three; and even in such a bit of a garden will be a

mountain covered with woods, a lake with an

island and a tiny bridge, a waterfall, and perhaps

an arbor and artistic lanterns. In the construction

of such gardens the dwellers in the crowded cities

seek to satisfy their longing for nature by looking

at a landscape which appeals to them. They

consider it as one considers a miniature by Isabey,

and are wonderfully proud of it.”

And here, as in most things Japanese, is an

admirable piece of general philosophy of life,

illustrating not only a theory of laying out gar-

dens, but of deriving a maximum of pleasure

from a minimum source.

C. M. P.

XVIII

Courtesy of Yamanaka &• Company

A JAPANESE INTERIOR IN A HOUSE AT TUXEDO PARK, N. Y. DESIGNED BY S. MORI

the Japanese, but to the fact that he comes of a

race of artists, whose ideals for thousands of years

back have been ideals of beauty. Physically he

lives in a beautiful country, a country aboundingly

picturesque in its conformation, its flora, its

costumes and its customs. Art in all things is so

inseparably a part of the people that neither can

be understood without the other.

Having, with a superficiality which brevity may

pardon, pointed out certain salient characteristics

of the Japanese idea of interior decoration, we

find that the principles of simplicity in the

interior are reversed in the garden, and that

if any principle is followed, it is complexity.

More accurately stated, the Japanese idea of

a garden, as opposed to that of most of the

great Italian and English garden builders, is that

the garden should be a place of pleasant surprises.

It must not be laid out by diagram, with obvious

“axes” and “centres,” with formal planting and

the like. The Japanese garden abounds in quaint

turnings and unexpected little bridges over pools

of aquatic plants. Here and there are stone

lanterns, miniature rock-gardens and rivulets.

A Japanese writer, who is by way of being an

authority on the matter, says: “In the western

garden one walks, for that seems to be the primary

purpose of its construction; but the Japanese

garden is planned to be looked at, and as a con-

sequence, the Japanese house, even upon the

tiniest plot of ground, has a garden. Attached to

the dwellings in the crowded cities, such as Tokio

or Osaka, you may even see gardens six feet by

three; and even in such a bit of a garden will be a

mountain covered with woods, a lake with an

island and a tiny bridge, a waterfall, and perhaps

an arbor and artistic lanterns. In the construction

of such gardens the dwellers in the crowded cities

seek to satisfy their longing for nature by looking

at a landscape which appeals to them. They

consider it as one considers a miniature by Isabey,

and are wonderfully proud of it.”

And here, as in most things Japanese, is an

admirable piece of general philosophy of life,

illustrating not only a theory of laying out gar-

dens, but of deriving a maximum of pleasure

from a minimum source.

C. M. P.

XVIII