Book Reviews

marines—represent any “school,” that school is

unknown or ignored today by nearly all our

painters. “Nature” and “conscientious study”

—does a generation of aspirants for tricky

“effects” and smart “impressions” think of these

in connection with painting? One can almost

fancy some of our contemporary exhibitors say-

ing: “Draw? Oh, no, I don’t draw; I paint”—

and if they do not say it they think it, even if they

realize what a mighty serious and important thing

“drawing” was to the men of the old school.

Richards should have been reckoned as the

logical successor of Inness and Wyant, excepting

that, unlike those two great landscapists, he did

not paint by formula. No matter how good the

formula may be, it is dangerous and detrimental

when it forms the basis of any work of art. Win-

slow Homer, generally considered one of our

greater marine painters, undoubtedly loved the

sea, and while he came very near to understanding

it, one cannot help feeling that he regarded it

more as a stage setting than as subject. It was the

background for some rendering of nautical genre.

In Mr. Morris’ intimate memoir of the life and

work of William T. Richards, one could have

wished, perhaps, a view of art on the part of the

biographer as broad and deep as that of his sub-

ject—there are no inaccuracies, but Richards’

work was of such import that even the largeness

and vitality of his character, which Mr. Morris

has shown in the sympathetic light of a warm

friendship, must seem almost secondary.

It is true enough that to understand paintings

we must understand the painter, and with Rich-

ards this was certainly true. Those who knew him

only on canvas knew a master painter and missed

a never-to-be-forgotten friend. Those who knew

him first as a friend, have, perhaps, been prone to

overlook his remarkable power as a painter. Free

of all studio “patter” and jargon of “tones,”

“values” and “technique” (though a master of

all), many people could not believe that the quiet,

genial man could be a really great painter without

talking about painting.

Mr. Richards’ art was a thing to him too vital

to bring into casual conversation—not his opinion

of his art, but the feeling so nearly akin to humility

with which he approached the ever-changing

phenomena of nature.

To the very end he was, to himself, still trying

to grasp his subject; he never fell back on a

“style,” or let his painting fall into the fatal rut

of self-assured mannerisms or “tricks.” And he

never felt that he had solved entirely the prob-

lems he loved and of whose rendering he was an

acknowledged master.

Yet all this Mr. Morris suggests, if he does not

actually define it, and his life of William T. Rich-

ards must come as a welcome memoir as well to

those who knew Mr. Richards in name or in per-

son, as to a younger generation which is in a fair

way to accept as landscape and marine painting

the canvases of those who now fill the public eye

in the galleries.

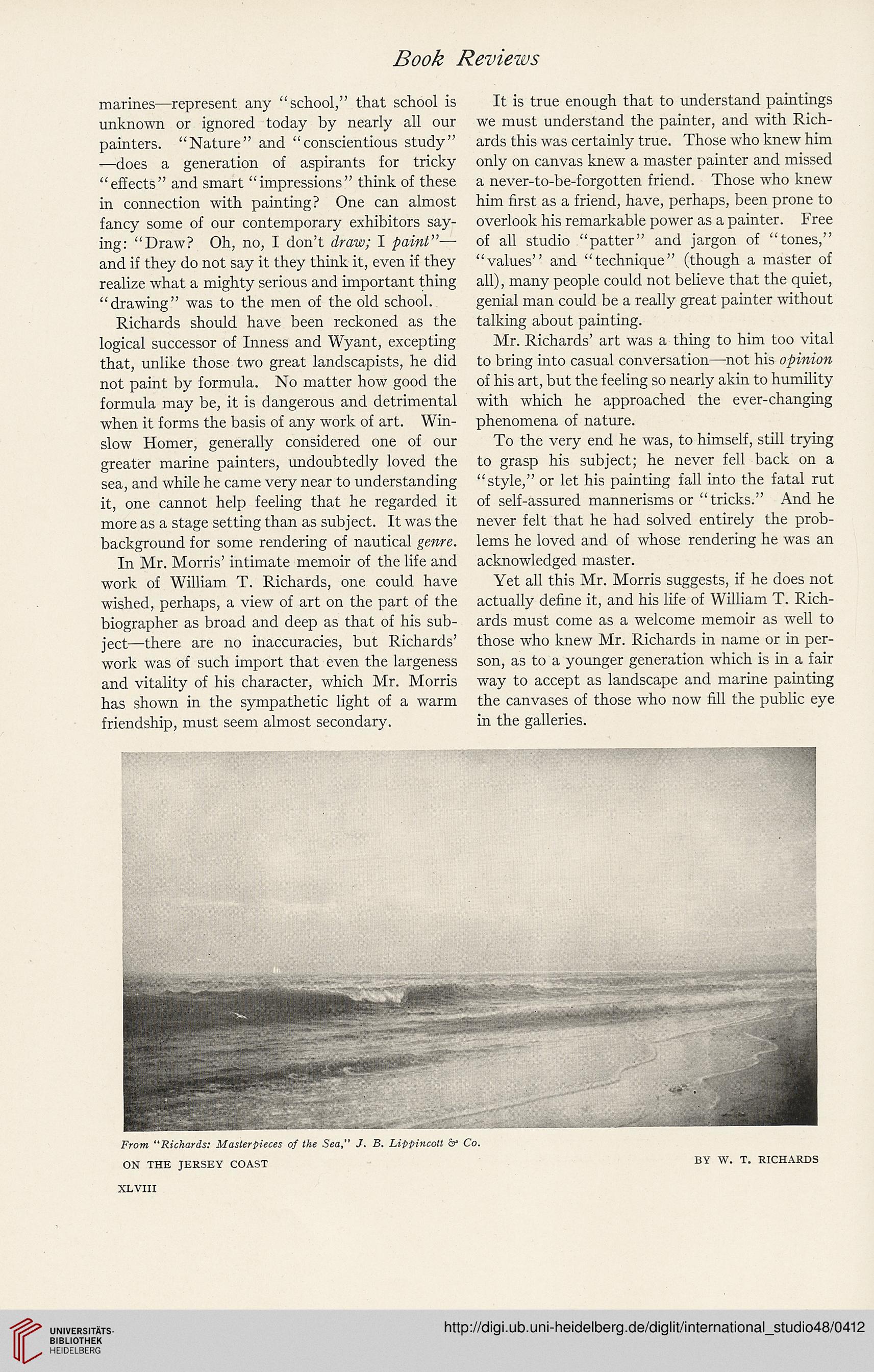

From “Richards: Masterpieces of the Sea,” J. B. Lippincott & Co.

ON THE JERSEY COAST

BY W. T. RICHARDS

XL VIII

marines—represent any “school,” that school is

unknown or ignored today by nearly all our

painters. “Nature” and “conscientious study”

—does a generation of aspirants for tricky

“effects” and smart “impressions” think of these

in connection with painting? One can almost

fancy some of our contemporary exhibitors say-

ing: “Draw? Oh, no, I don’t draw; I paint”—

and if they do not say it they think it, even if they

realize what a mighty serious and important thing

“drawing” was to the men of the old school.

Richards should have been reckoned as the

logical successor of Inness and Wyant, excepting

that, unlike those two great landscapists, he did

not paint by formula. No matter how good the

formula may be, it is dangerous and detrimental

when it forms the basis of any work of art. Win-

slow Homer, generally considered one of our

greater marine painters, undoubtedly loved the

sea, and while he came very near to understanding

it, one cannot help feeling that he regarded it

more as a stage setting than as subject. It was the

background for some rendering of nautical genre.

In Mr. Morris’ intimate memoir of the life and

work of William T. Richards, one could have

wished, perhaps, a view of art on the part of the

biographer as broad and deep as that of his sub-

ject—there are no inaccuracies, but Richards’

work was of such import that even the largeness

and vitality of his character, which Mr. Morris

has shown in the sympathetic light of a warm

friendship, must seem almost secondary.

It is true enough that to understand paintings

we must understand the painter, and with Rich-

ards this was certainly true. Those who knew him

only on canvas knew a master painter and missed

a never-to-be-forgotten friend. Those who knew

him first as a friend, have, perhaps, been prone to

overlook his remarkable power as a painter. Free

of all studio “patter” and jargon of “tones,”

“values” and “technique” (though a master of

all), many people could not believe that the quiet,

genial man could be a really great painter without

talking about painting.

Mr. Richards’ art was a thing to him too vital

to bring into casual conversation—not his opinion

of his art, but the feeling so nearly akin to humility

with which he approached the ever-changing

phenomena of nature.

To the very end he was, to himself, still trying

to grasp his subject; he never fell back on a

“style,” or let his painting fall into the fatal rut

of self-assured mannerisms or “tricks.” And he

never felt that he had solved entirely the prob-

lems he loved and of whose rendering he was an

acknowledged master.

Yet all this Mr. Morris suggests, if he does not

actually define it, and his life of William T. Rich-

ards must come as a welcome memoir as well to

those who knew Mr. Richards in name or in per-

son, as to a younger generation which is in a fair

way to accept as landscape and marine painting

the canvases of those who now fill the public eye

in the galleries.

From “Richards: Masterpieces of the Sea,” J. B. Lippincott & Co.

ON THE JERSEY COAST

BY W. T. RICHARDS

XL VIII