In the Galleries

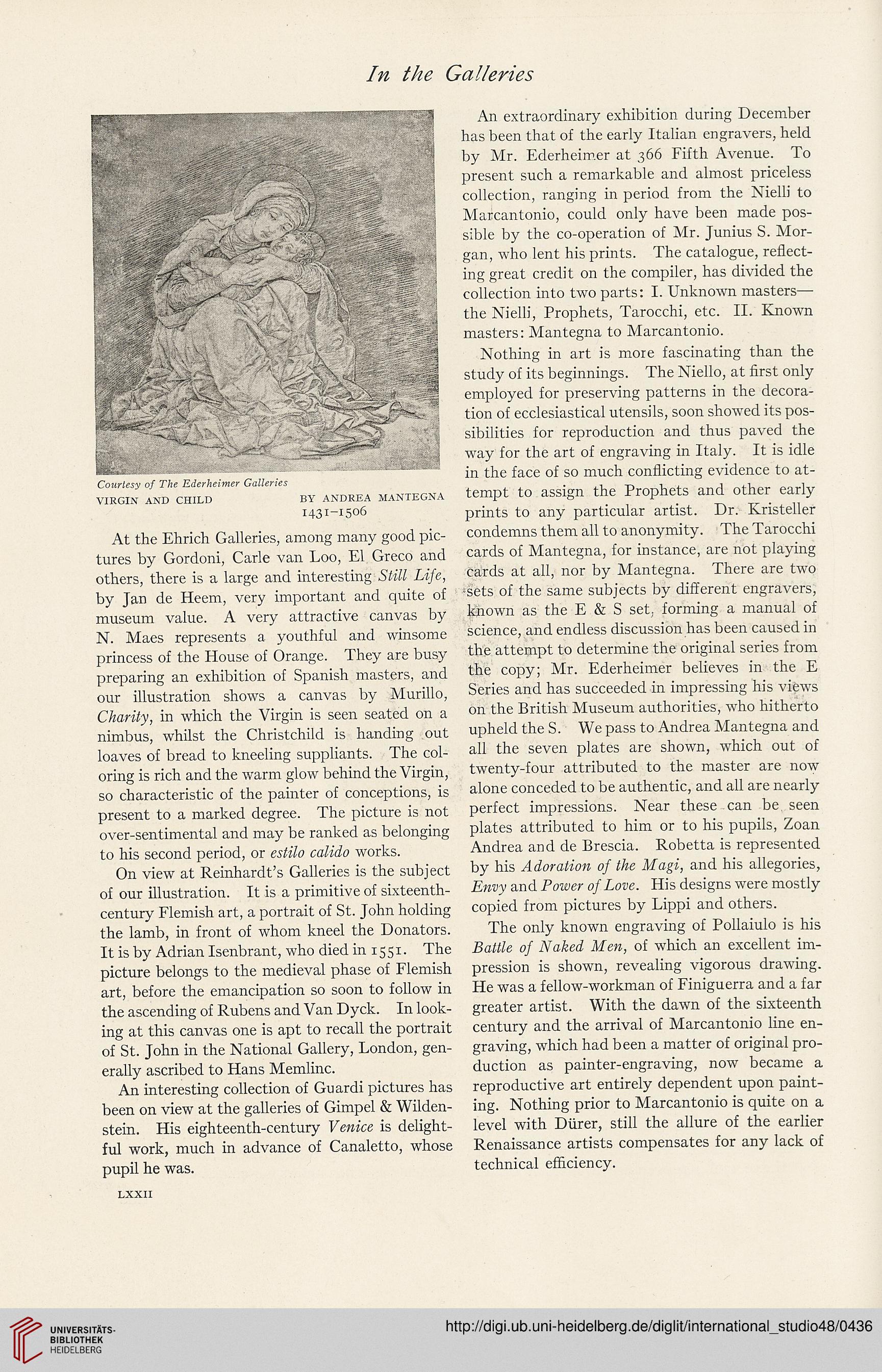

Courtesy of The Ederheimer Galleries

VIRGIN AND CHILD BY ANDREA MANTEGNA

1431-1506

At the Ehrich Galleries, among many good pic-

tures by Gordoni, Carle van Loo, El Greco and

others, there is a large and interesting Still Life,

by Jan de Heem, very important and quite of

museum value. A very attractive canvas by

N. Maes represents a youthful and winsome

princess of the House of Orange. They are busy

preparing an exhibition of Spanish masters, and

our illustration shows a canvas by Murillo,

Charity, in which the Virgin is seen seated on a

nimbus, whilst the Christchild is handing out

loaves of bread to kneeling suppliants. The col-

oring is rich and the warm glow behind the Virgin,

so characteristic of the painter of conceptions, is

present to a marked degree. The picture is not

over-sentimental and may be ranked as belonging

to his second period, or estilo calido works.

On view at Reinhardt’s Galleries is the subject

of our illustration. It is a primitive of sixteenth-

century Flemish art, a portrait of St. John holding

the lamb, in front of whom kneel the Donators.

It is by Adrian Isenbrant, who died in 1551. The

picture belongs to the medieval phase of Flemish

art, before the emancipation so soon to follow in

the ascending of Rubens and Van Dyck. In look-

ing at this canvas one is apt to recall the portrait

of St. John in the National Gallery, London, gen-

erally ascribed to Hans Memlinc.

An interesting collection of Guardi pictures has

been on view at the galleries of Gimpel & Wilden-

stein. His eighteenth-century Venice is delight-

ful work, much in advance of Canaletto, whose

pupil he was.

An extraordinary exhibition during December

has been that of the early Italian engravers, held

by Mr. Ederheimer at 366 Fifth Avenue. To

present such a remarkable and almost priceless

collection, ranging in period from the Nielli to

Marcantonio, could only have been made pos-

sible by the co-operation of Mr. Junius S. Mor-

gan, who lent his prints. The catalogue, reflect-

ing great credit on the compiler, has divided the

collection into two parts: I. Unknown masters—-

the Nielli, Prophets, Tarocchi, etc. II. Known

masters: Mantegna to Marcantonio.

Nothing in art is more fascinating than the

study of its beginnings. The Niello, at first only

employed for preserving patterns in the decora-

tion of ecclesiastical utensils, soon showed its pos-

sibilities for reproduction and thus paved the

way for the art of engraving in Italy. It is idle

in the face of so much conflicting evidence to at-

tempt to assign the Prophets and other early

prints to any particular artist. Dr. Kristeller

condemns them all to anonymity. The Tarocchi

cards of Mantegna, for instance, are not playing

cards at all, nor by Mantegna. There are two

’Sets of the same subjects by different engravers,

known as the E & S set, forming a manual of

science, and endless discussion has been caused in

the attempt to determine the original series from

the copy; Mr. Ederheimer believes in the E

Series and has succeeded in impressing his views

on the British Museum authorities, who hitherto

upheld the S. We pass to Andrea Mantegna and

all the seven plates are shown, which out of

twenty-four attributed to the master are now

alone conceded to be authentic, and all are nearly

perfect impressions. Near these can be seen

plates attributed to him or to his pupils, Zoan

Andrea and de Brescia. Robetta is represented

by his Adoration of the Magi, and his allegories,

Envy and Power of Love. His designs were mostly

copied from pictures by Lippi and others.

The only known engraving of Pollaiulo is his

Battle of Naked Men, of which an excellent im-

pression is shown, revealing vigorous drawing.

He was a fellow-workman of Finiguerra and a far

greater artist. With the dawn of the sixteenth

century and the arrival of Marcantonio line en-

graving, which had been a matter of original pro-

duction as painter-engraving, now became a

reproductive art entirely dependent upon paint-

ing. Nothing prior to Marcantonio is quite on a

level with Diirer, still the allure of the earlier

Renaissance artists compensates for any lack of

technical efficiency.

LXXII

Courtesy of The Ederheimer Galleries

VIRGIN AND CHILD BY ANDREA MANTEGNA

1431-1506

At the Ehrich Galleries, among many good pic-

tures by Gordoni, Carle van Loo, El Greco and

others, there is a large and interesting Still Life,

by Jan de Heem, very important and quite of

museum value. A very attractive canvas by

N. Maes represents a youthful and winsome

princess of the House of Orange. They are busy

preparing an exhibition of Spanish masters, and

our illustration shows a canvas by Murillo,

Charity, in which the Virgin is seen seated on a

nimbus, whilst the Christchild is handing out

loaves of bread to kneeling suppliants. The col-

oring is rich and the warm glow behind the Virgin,

so characteristic of the painter of conceptions, is

present to a marked degree. The picture is not

over-sentimental and may be ranked as belonging

to his second period, or estilo calido works.

On view at Reinhardt’s Galleries is the subject

of our illustration. It is a primitive of sixteenth-

century Flemish art, a portrait of St. John holding

the lamb, in front of whom kneel the Donators.

It is by Adrian Isenbrant, who died in 1551. The

picture belongs to the medieval phase of Flemish

art, before the emancipation so soon to follow in

the ascending of Rubens and Van Dyck. In look-

ing at this canvas one is apt to recall the portrait

of St. John in the National Gallery, London, gen-

erally ascribed to Hans Memlinc.

An interesting collection of Guardi pictures has

been on view at the galleries of Gimpel & Wilden-

stein. His eighteenth-century Venice is delight-

ful work, much in advance of Canaletto, whose

pupil he was.

An extraordinary exhibition during December

has been that of the early Italian engravers, held

by Mr. Ederheimer at 366 Fifth Avenue. To

present such a remarkable and almost priceless

collection, ranging in period from the Nielli to

Marcantonio, could only have been made pos-

sible by the co-operation of Mr. Junius S. Mor-

gan, who lent his prints. The catalogue, reflect-

ing great credit on the compiler, has divided the

collection into two parts: I. Unknown masters—-

the Nielli, Prophets, Tarocchi, etc. II. Known

masters: Mantegna to Marcantonio.

Nothing in art is more fascinating than the

study of its beginnings. The Niello, at first only

employed for preserving patterns in the decora-

tion of ecclesiastical utensils, soon showed its pos-

sibilities for reproduction and thus paved the

way for the art of engraving in Italy. It is idle

in the face of so much conflicting evidence to at-

tempt to assign the Prophets and other early

prints to any particular artist. Dr. Kristeller

condemns them all to anonymity. The Tarocchi

cards of Mantegna, for instance, are not playing

cards at all, nor by Mantegna. There are two

’Sets of the same subjects by different engravers,

known as the E & S set, forming a manual of

science, and endless discussion has been caused in

the attempt to determine the original series from

the copy; Mr. Ederheimer believes in the E

Series and has succeeded in impressing his views

on the British Museum authorities, who hitherto

upheld the S. We pass to Andrea Mantegna and

all the seven plates are shown, which out of

twenty-four attributed to the master are now

alone conceded to be authentic, and all are nearly

perfect impressions. Near these can be seen

plates attributed to him or to his pupils, Zoan

Andrea and de Brescia. Robetta is represented

by his Adoration of the Magi, and his allegories,

Envy and Power of Love. His designs were mostly

copied from pictures by Lippi and others.

The only known engraving of Pollaiulo is his

Battle of Naked Men, of which an excellent im-

pression is shown, revealing vigorous drawing.

He was a fellow-workman of Finiguerra and a far

greater artist. With the dawn of the sixteenth

century and the arrival of Marcantonio line en-

graving, which had been a matter of original pro-

duction as painter-engraving, now became a

reproductive art entirely dependent upon paint-

ing. Nothing prior to Marcantonio is quite on a

level with Diirer, still the allure of the earlier

Renaissance artists compensates for any lack of

technical efficiency.

LXXII