Standardized Sentiment in Current Art

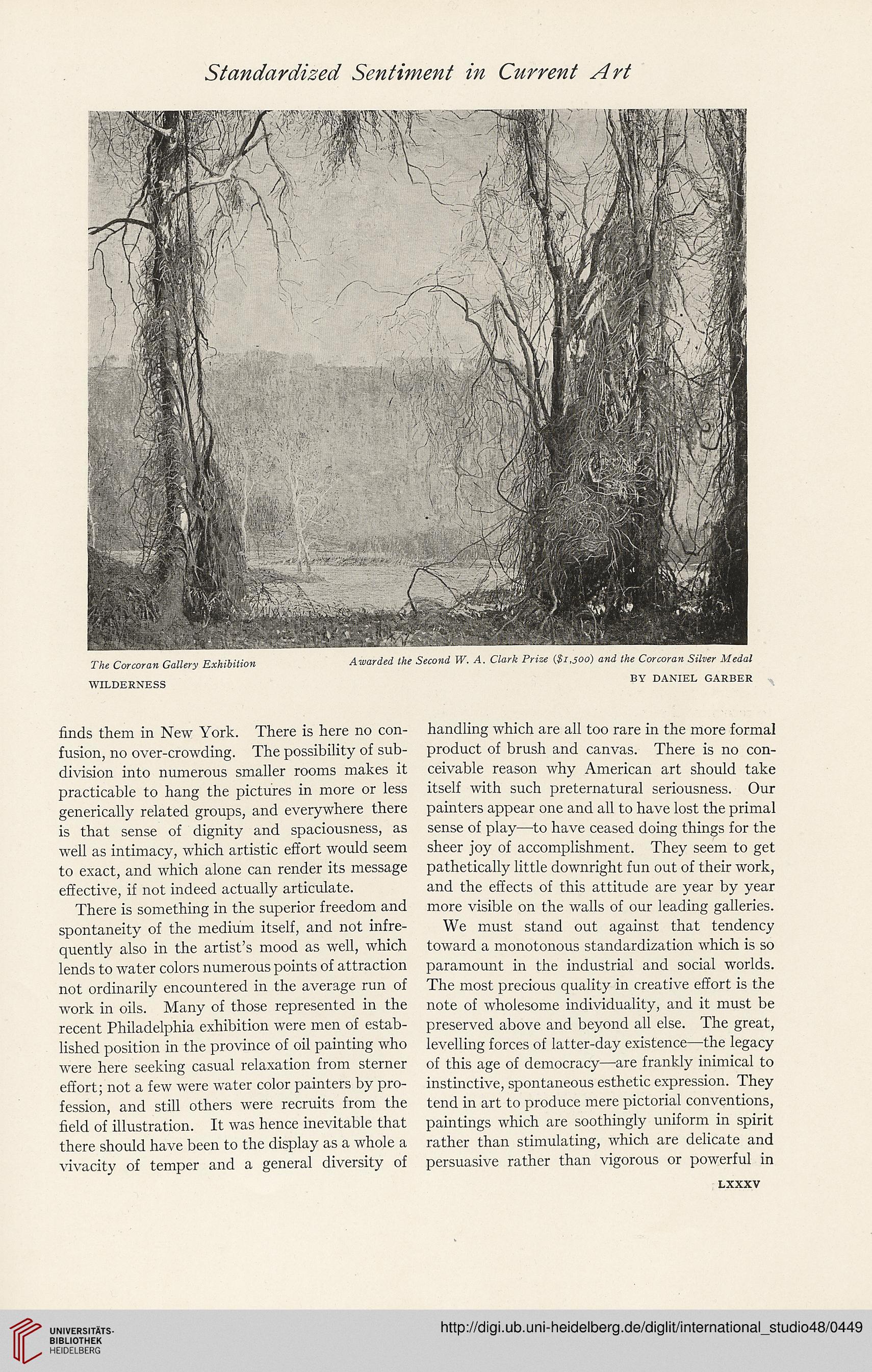

The Corcoran Gallery Exhibition Awarded the Second W. A. Clark Prize ($1,500) and the Corcoran Silver Medal

WILDERNESS

BY DANIEL GARBER

finds them in New York. There is here no con-

fusion, no over-crowding. The possibility of sub-

division into numerous smaller rooms makes it

practicable to hang the pictures in more or less

generically related groups, and everywhere there

is that sense of dignity and spaciousness, as

well as intimacy, which artistic effort would seem

to exact, and which alone can render its message

effective, if not indeed actually articulate.

There is something in the superior freedom and

spontaneity of the medium itself, and not infre-

quently also in the artist’s mood as well, which

lends to water colors numerous points of attraction

not ordinarily encountered in the average run of

work in oils. Many of those represented in the

recent Philadelphia exhibition were men of estab-

lished position in the province of oil painting who

were here seeking casual relaxation from sterner

effort; not a few were water color painters by pro-

fession, and still others were recruits from the

field of illustration. It was hence inevitable that

there should have been to the display as a whole a

vivacity of temper and a general diversity of

handling which are all too rare in the more formal

product of brush and canvas. There is no con-

ceivable reason why American art should take

itself with such preternatural seriousness. Our

painters appear one and all to have lost the primal

sense of play—to have ceased doing things for the

sheer joy of accomplishment. They seem to get

pathetically little downright fun out of their work,

and the effects of this attitude are year by year

more visible on the walls of our leading galleries.

We must stand out against that tendency

toward a monotonous standardization which is so

paramount in the industrial and social worlds.

The most precious quality in creative effort is the

note of wholesome individuality, and it must be

preserved above and beyond all else. The great,

levelling forces of latter-day existence—the legacy

of this age of democracy—are frankly inimical to

instinctive, spontaneous esthetic expression. They

tend in art to produce mere pictorial conventions,

paintings which are soothingly uniform in spirit

rather than stimulating, which are delicate and

persuasive rather than vigorous or powerful in

LXXXV

The Corcoran Gallery Exhibition Awarded the Second W. A. Clark Prize ($1,500) and the Corcoran Silver Medal

WILDERNESS

BY DANIEL GARBER

finds them in New York. There is here no con-

fusion, no over-crowding. The possibility of sub-

division into numerous smaller rooms makes it

practicable to hang the pictures in more or less

generically related groups, and everywhere there

is that sense of dignity and spaciousness, as

well as intimacy, which artistic effort would seem

to exact, and which alone can render its message

effective, if not indeed actually articulate.

There is something in the superior freedom and

spontaneity of the medium itself, and not infre-

quently also in the artist’s mood as well, which

lends to water colors numerous points of attraction

not ordinarily encountered in the average run of

work in oils. Many of those represented in the

recent Philadelphia exhibition were men of estab-

lished position in the province of oil painting who

were here seeking casual relaxation from sterner

effort; not a few were water color painters by pro-

fession, and still others were recruits from the

field of illustration. It was hence inevitable that

there should have been to the display as a whole a

vivacity of temper and a general diversity of

handling which are all too rare in the more formal

product of brush and canvas. There is no con-

ceivable reason why American art should take

itself with such preternatural seriousness. Our

painters appear one and all to have lost the primal

sense of play—to have ceased doing things for the

sheer joy of accomplishment. They seem to get

pathetically little downright fun out of their work,

and the effects of this attitude are year by year

more visible on the walls of our leading galleries.

We must stand out against that tendency

toward a monotonous standardization which is so

paramount in the industrial and social worlds.

The most precious quality in creative effort is the

note of wholesome individuality, and it must be

preserved above and beyond all else. The great,

levelling forces of latter-day existence—the legacy

of this age of democracy—are frankly inimical to

instinctive, spontaneous esthetic expression. They

tend in art to produce mere pictorial conventions,

paintings which are soothingly uniform in spirit

rather than stimulating, which are delicate and

persuasive rather than vigorous or powerful in

LXXXV