20

THE INTERNATIONAL STUDIO

November, 1912

A LITTLE JOURNEY TO THE

STUDIO OF AN ARTIST-

• ARTISAN

If genius consists primarily of a capac-

ity for taking infinite pains, there is a

genius at work in a tiny New Jersey suburb

of New York, His name is Joseph Fischer

and he is a German, a fact apparent both in

his speech and in the brand of his whole-

hearted hospitality. Coming to this coun-

try in 1881 he was after a time employed

by Tiffany & Co. as a designer and mod-

eler in their art metal department, where

he remained- for fourteen years, benefiting

in many ways from the connection, though

achieving but little of the public recogni-

tion to which his extraordinary skill en-

titles him. Six years ago he became a free

lance and in that time has executed many

notable commissions formanufacturers and

private individuals, numbering among

them various prize cups, trophies, medal-

lions and unique table services.

Remarkable as Mr. Fischer’s work is in

the lines indicated, the greater part of the

fame which should, and doubtless will, be

his, .must be based on his achievements in

still another branch of artcraft, that of

ivory carving. This is where the infinite

pains and patience of his genius have their

most striking exemplification. It may

safely be said without fear of controversy

that in this field he has no rival outside of

Japan.

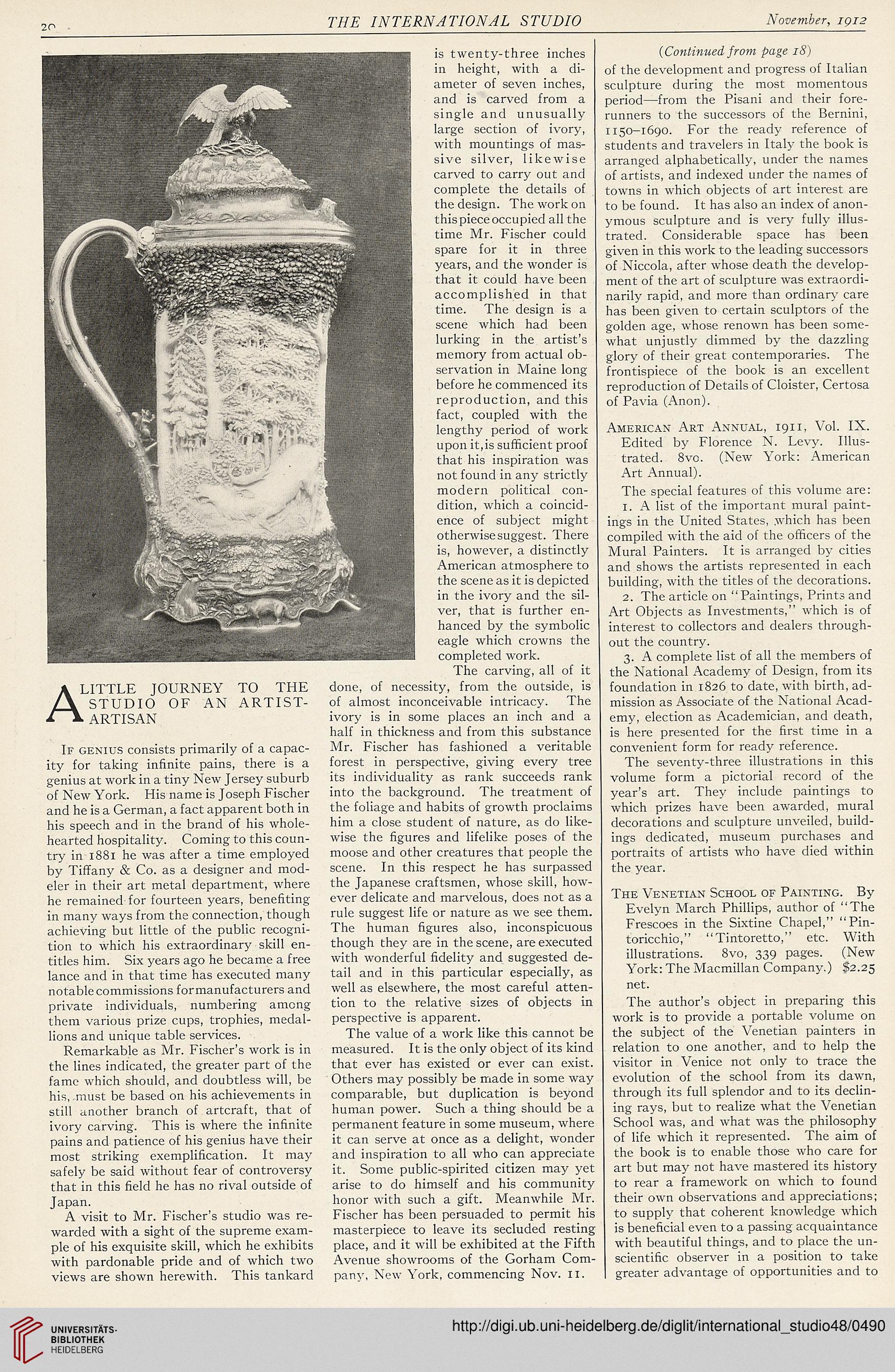

A visit to Mr. Fischer’s studio was re-

warded with a sight of the supreme exam-

ple of his exquisite skill, which he exhibits

with pardonable pride and of which two

views are shown herewith. This tankard

is twenty-three inches

in height, with a di-

ameter of seven inches,

and is carved from a

single and unusually

large section of ivory,

with mountings of mas-

sive silver, likewise

carved to carry out and

complete the details of

the design. The work on

this piece occupied all the

time Mr. Fischer could

spare for it in three

years, and the wonder is

that it could have been

accomplished in that

time. The design is a

scene which had been

lurking in the artist’s

memory from actual ob-

servation in Maine long

before he commenced its

reproduction, and this

fact, coupled with the

lengthy period of work

upon it,is sufficient proof

that his inspiration was

not found in any strictly

modern political con-

dition, which a coincid-

ence of subject might

otherwise suggest. There

is, however, a distinctly

American atmosphere to

the scene as it is depicted

in the ivory and the sil-

ver, that is further en-

hanced by the symbolic

eagle which crowns the

completed work.

The carving, all of it

done, of necessity, from the outside, is

of almost inconceivable intricacy. The

ivory is in some places an inch and a

half in thickness and from this substance

Mr. Fischer has fashioned a veritable

forest in perspective, giving every tree

its individuality as rank succeeds rank

into the background. The treatment of

the foliage and habits of growth proclaims

him a close student of nature, as do like-

wise the figures and lifelike poses of the

moose and other creatures that people the

scene. In this respect he has surpassed

the Japanese craftsmen, whose skill, how-

ever delicate and marvelous, does not as a

rule suggest life or nature as we see them.

The human figures also, inconspicuous

though they are in the scene, are executed

with wonderful fidelity and suggested de-

tail and in this particular especially, as

well as elsewhere, the most careful atten-

tion to the relative sizes of objects in

perspective is apparent.

The value of a work like this cannot be

measured. It is the only object of its kind

that ever has existed or ever can exist.

Others may possibly be made in some way

comparable, but duplication is beyond

human power. Such a thing should be a

permanent feature in some museum, where

it can serve at once as a delight, wonder

and inspiration to all who can appreciate

it. Some public-spirited citizen may yet

arise to do himself and his community

honor with such a gift. Meanwhile Mr.

Fischer has been persuaded to permit his

masterpiece to leave its secluded resting

place, and it will be exhibited at the Fifth

Avenue showrooms of the Gorham Com-

pany, New York, commencing Nov. II.

{Continued, from page 18)

of the development and progress of Italian

sculpture during the most momentous

period—from the Pisani and their fore-

runners to the successors of the Bernini,

1150-1690. For the ready reference of

students and travelers in Italy the book is

arranged alphabetically, under the names

of artists, and indexed under the names of

towns in which objects of art interest are

to be found. It has also an index of anon-

ymous sculpture and is very fully illus-

trated. Considerable space has been

given in this work to the leading successors

of Niccola, after whose death the develop-

ment of the art of sculpture was extraordi-

narily rapid, and more than ordinary care

has been given to certain sculptors of the

golden age, whose renown has been some-

what unjustly dimmed by the dazzling

glory of their great contemporaries. The

frontispiece of the book is an excellent

reproduction of Details of Cloister, Certosa

of Pavia (Anon).

American Art Annual, 1911, Vol. IX.

Edited by Florence N. Levy. Illus-

trated. 8vo. (New York: American

Art Annual).

The special features of this volume are:

1. A list of the important mural paint-

ings in the United States, .which has been

compiled with the aid of the officers of the

Mural Painters. It is arranged by cities

and shows the artists represented in each

building, with the titles of the decorations.

2. The article on “Paintings, Prints and

Art Objects as Investments,” which is of

interest to collectors and dealers through-

out the country.

3. A complete list of all the members of

the National Academy of Design, from its

foundation in 1826 to date, with birth, ad-

mission as Associate of the National Acad-

emy, election as Academician, and death,

is here presented for the first time in a

convenient form for ready reference.

The seventy-three illustrations in this

volume form a pictorial record of the

year’s art. They include paintings to

which prizes have been awarded, mural

decorations and sculpture unveiled, build-

ings dedicated, museum purchases and

portraits of artists who have died within

the year.

The Venetian School of Painting. By

Evelyn March Phillips, author of “The

Frescoes in the Sixtine Chapel,” “Pin-

toricchio,” “Tintoretto,” etc. With

illustrations. 8vo, 339 pages. (New

York: The Macmillan Company.) $2.25

net.

The author’s object in preparing this

work is to provide a portable volume on

the subject of the Venetian painters in

relation to one another, and to help the

visitor in Venice not only to trace the

evolution of the school from its dawn,

through its full splendor and to its declin-

ing rays, but to realize what the Venetian

School was, and what was the philosophy

of life which it represented. The aim of

the book is to enable those who care for

art but may not have mastered its history

to rear a framework on which to found

their own observations and appreciations;

to supply that coherent knowledge which

is beneficial even to a passing acquaintance

with beautiful things, and to place the un-

scientific observer in a position to take

greater advantage of opportunities and to

THE INTERNATIONAL STUDIO

November, 1912

A LITTLE JOURNEY TO THE

STUDIO OF AN ARTIST-

• ARTISAN

If genius consists primarily of a capac-

ity for taking infinite pains, there is a

genius at work in a tiny New Jersey suburb

of New York, His name is Joseph Fischer

and he is a German, a fact apparent both in

his speech and in the brand of his whole-

hearted hospitality. Coming to this coun-

try in 1881 he was after a time employed

by Tiffany & Co. as a designer and mod-

eler in their art metal department, where

he remained- for fourteen years, benefiting

in many ways from the connection, though

achieving but little of the public recogni-

tion to which his extraordinary skill en-

titles him. Six years ago he became a free

lance and in that time has executed many

notable commissions formanufacturers and

private individuals, numbering among

them various prize cups, trophies, medal-

lions and unique table services.

Remarkable as Mr. Fischer’s work is in

the lines indicated, the greater part of the

fame which should, and doubtless will, be

his, .must be based on his achievements in

still another branch of artcraft, that of

ivory carving. This is where the infinite

pains and patience of his genius have their

most striking exemplification. It may

safely be said without fear of controversy

that in this field he has no rival outside of

Japan.

A visit to Mr. Fischer’s studio was re-

warded with a sight of the supreme exam-

ple of his exquisite skill, which he exhibits

with pardonable pride and of which two

views are shown herewith. This tankard

is twenty-three inches

in height, with a di-

ameter of seven inches,

and is carved from a

single and unusually

large section of ivory,

with mountings of mas-

sive silver, likewise

carved to carry out and

complete the details of

the design. The work on

this piece occupied all the

time Mr. Fischer could

spare for it in three

years, and the wonder is

that it could have been

accomplished in that

time. The design is a

scene which had been

lurking in the artist’s

memory from actual ob-

servation in Maine long

before he commenced its

reproduction, and this

fact, coupled with the

lengthy period of work

upon it,is sufficient proof

that his inspiration was

not found in any strictly

modern political con-

dition, which a coincid-

ence of subject might

otherwise suggest. There

is, however, a distinctly

American atmosphere to

the scene as it is depicted

in the ivory and the sil-

ver, that is further en-

hanced by the symbolic

eagle which crowns the

completed work.

The carving, all of it

done, of necessity, from the outside, is

of almost inconceivable intricacy. The

ivory is in some places an inch and a

half in thickness and from this substance

Mr. Fischer has fashioned a veritable

forest in perspective, giving every tree

its individuality as rank succeeds rank

into the background. The treatment of

the foliage and habits of growth proclaims

him a close student of nature, as do like-

wise the figures and lifelike poses of the

moose and other creatures that people the

scene. In this respect he has surpassed

the Japanese craftsmen, whose skill, how-

ever delicate and marvelous, does not as a

rule suggest life or nature as we see them.

The human figures also, inconspicuous

though they are in the scene, are executed

with wonderful fidelity and suggested de-

tail and in this particular especially, as

well as elsewhere, the most careful atten-

tion to the relative sizes of objects in

perspective is apparent.

The value of a work like this cannot be

measured. It is the only object of its kind

that ever has existed or ever can exist.

Others may possibly be made in some way

comparable, but duplication is beyond

human power. Such a thing should be a

permanent feature in some museum, where

it can serve at once as a delight, wonder

and inspiration to all who can appreciate

it. Some public-spirited citizen may yet

arise to do himself and his community

honor with such a gift. Meanwhile Mr.

Fischer has been persuaded to permit his

masterpiece to leave its secluded resting

place, and it will be exhibited at the Fifth

Avenue showrooms of the Gorham Com-

pany, New York, commencing Nov. II.

{Continued, from page 18)

of the development and progress of Italian

sculpture during the most momentous

period—from the Pisani and their fore-

runners to the successors of the Bernini,

1150-1690. For the ready reference of

students and travelers in Italy the book is

arranged alphabetically, under the names

of artists, and indexed under the names of

towns in which objects of art interest are

to be found. It has also an index of anon-

ymous sculpture and is very fully illus-

trated. Considerable space has been

given in this work to the leading successors

of Niccola, after whose death the develop-

ment of the art of sculpture was extraordi-

narily rapid, and more than ordinary care

has been given to certain sculptors of the

golden age, whose renown has been some-

what unjustly dimmed by the dazzling

glory of their great contemporaries. The

frontispiece of the book is an excellent

reproduction of Details of Cloister, Certosa

of Pavia (Anon).

American Art Annual, 1911, Vol. IX.

Edited by Florence N. Levy. Illus-

trated. 8vo. (New York: American

Art Annual).

The special features of this volume are:

1. A list of the important mural paint-

ings in the United States, .which has been

compiled with the aid of the officers of the

Mural Painters. It is arranged by cities

and shows the artists represented in each

building, with the titles of the decorations.

2. The article on “Paintings, Prints and

Art Objects as Investments,” which is of

interest to collectors and dealers through-

out the country.

3. A complete list of all the members of

the National Academy of Design, from its

foundation in 1826 to date, with birth, ad-

mission as Associate of the National Acad-

emy, election as Academician, and death,

is here presented for the first time in a

convenient form for ready reference.

The seventy-three illustrations in this

volume form a pictorial record of the

year’s art. They include paintings to

which prizes have been awarded, mural

decorations and sculpture unveiled, build-

ings dedicated, museum purchases and

portraits of artists who have died within

the year.

The Venetian School of Painting. By

Evelyn March Phillips, author of “The

Frescoes in the Sixtine Chapel,” “Pin-

toricchio,” “Tintoretto,” etc. With

illustrations. 8vo, 339 pages. (New

York: The Macmillan Company.) $2.25

net.

The author’s object in preparing this

work is to provide a portable volume on

the subject of the Venetian painters in

relation to one another, and to help the

visitor in Venice not only to trace the

evolution of the school from its dawn,

through its full splendor and to its declin-

ing rays, but to realize what the Venetian

School was, and what was the philosophy

of life which it represented. The aim of

the book is to enable those who care for

art but may not have mastered its history

to rear a framework on which to found

their own observations and appreciations;

to supply that coherent knowledge which

is beneficial even to a passing acquaintance

with beautiful things, and to place the un-

scientific observer in a position to take

greater advantage of opportunities and to