Revolutions and Reactions in Painting

the

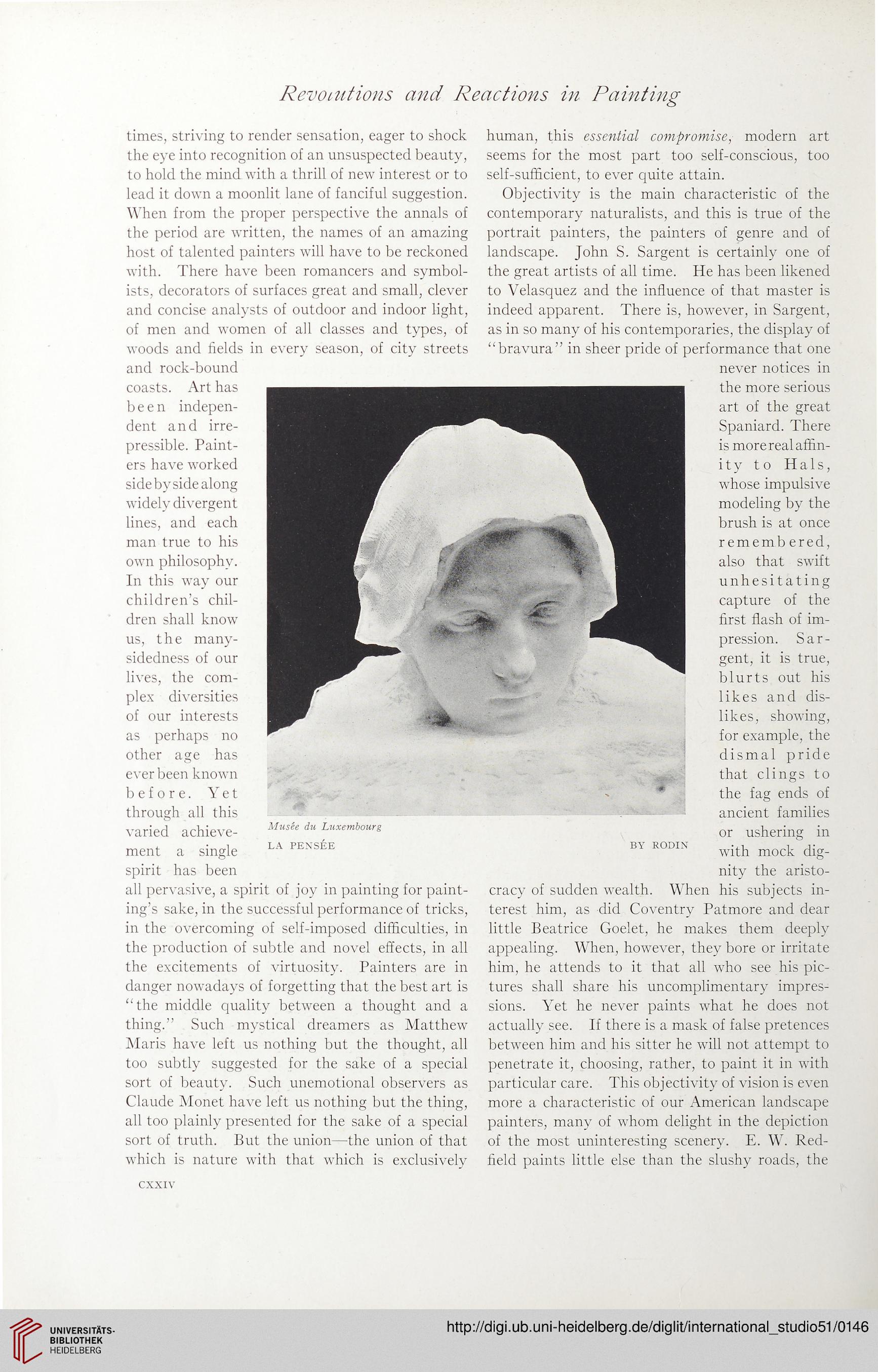

BY RODIN

art

too

Musee du Luxembourg

LA PENSEE

times, striving to render sensation, eager to shock

the eye into recognition of an unsuspected beauty,

to hold the mind with a thrill of new interest or to

lead it down a moonlit lane of fanciful suggestion.

When from the proper perspective the annals of

the period are written, the names of an amazing

host of talented painters will have to be reckoned

with. There have been romancers and symbol-

ists, decorators of surfaces great and small, clever

and concise analysts of outdoor and indoor light,

of men and women of all classes and types, of

woods and fields in every season, of city streets

and rock-bound

coasts. Art has

been indepen¬

dent and irre¬

pressible. Paint¬

ers have worked

side by side along

widely divergent

lines, and each

man true to his

own philosophy.

In this way our

children’s chil¬

dren shall know

us, the many-

sidedness of our

lives, the com¬

plex diversities

of our interests

as perhaps no

other age has

ever been known

before. Yet

through all this

varied achieve¬

ment a single

spirit has been

all pervasive, a spirit of joy in painting for paint-

ing’s sake, in the successful performance of tricks,

in the overcoming of self-imposed difficulties, in

the production of subtle and novel effects, in all

the excitements of virtuosity. Painters are in

danger nowadays of forgetting that the best art is

“the middle quality between a thought and a

thing.” Such mystical dreamers as Matthew

Maris have left us nothing but the thought, all

too subtly suggested for the sake of a special

sort of beauty. Such unemotional observers as

Claude Monet have left us nothing but the thing,

all too plainly presented for the sake of a special

sort of truth. But the union—the union of that

which is nature with that which is exclusively

human, this essential compromise, modern

seems for the most part too self-conscious,

self-sufficient, to ever quite attain.

Objectivity is the main characteristic of

contemporary naturalists, and this is true of the

portrait painters, the painters of genre and of

landscape. John S. Sargent is certainly one of

the great artists of all time. He has been likened

to Velasquez and the influence of that master is

indeed apparent. There is, however, in Sargent,

as in so many of his contemporaries, the display of

“bravura” in sheer pride of performance that one

never notices in

the more serious

art of the great

Spaniard. There

is more real affin-

ity to Hals,

whose impulsive

modeling by the

brush is at once

remembered,

also that swift

unhesitating

capture of the

first flash of im-

pression. Sar-

gent, it is true,

blurts out his

likes and dis-

likes, showing,

for example, the

dismal pride

that clings to

the fag ends of

ancient families

or ushering in

with mock dig-

nity the aristo-

his subjects in-

cracy of sudden wealth. When

terest him, as did Coventry Patmore and dear

little Beatrice Goelet, he makes them deeply

appealing. When, however, they bore or irritate

him, he attends to it that all who see his pic-

tures shall share his uncomplimentary impres-

sions. Yet he never paints what he does not

actually see. If there is a mask of false pretences

between him and his sitter he will not attempt to

penetrate it, choosing, rather, to paint it in with

particular care. This objectivity of vision is even

more a characteristic of our American landscape

painters, many of whom delight in the depiction

of the most uninteresting scenery. E. W. Red-

field paints little else than the slushy roads, the

cxxiv

the

BY RODIN

art

too

Musee du Luxembourg

LA PENSEE

times, striving to render sensation, eager to shock

the eye into recognition of an unsuspected beauty,

to hold the mind with a thrill of new interest or to

lead it down a moonlit lane of fanciful suggestion.

When from the proper perspective the annals of

the period are written, the names of an amazing

host of talented painters will have to be reckoned

with. There have been romancers and symbol-

ists, decorators of surfaces great and small, clever

and concise analysts of outdoor and indoor light,

of men and women of all classes and types, of

woods and fields in every season, of city streets

and rock-bound

coasts. Art has

been indepen¬

dent and irre¬

pressible. Paint¬

ers have worked

side by side along

widely divergent

lines, and each

man true to his

own philosophy.

In this way our

children’s chil¬

dren shall know

us, the many-

sidedness of our

lives, the com¬

plex diversities

of our interests

as perhaps no

other age has

ever been known

before. Yet

through all this

varied achieve¬

ment a single

spirit has been

all pervasive, a spirit of joy in painting for paint-

ing’s sake, in the successful performance of tricks,

in the overcoming of self-imposed difficulties, in

the production of subtle and novel effects, in all

the excitements of virtuosity. Painters are in

danger nowadays of forgetting that the best art is

“the middle quality between a thought and a

thing.” Such mystical dreamers as Matthew

Maris have left us nothing but the thought, all

too subtly suggested for the sake of a special

sort of beauty. Such unemotional observers as

Claude Monet have left us nothing but the thing,

all too plainly presented for the sake of a special

sort of truth. But the union—the union of that

which is nature with that which is exclusively

human, this essential compromise, modern

seems for the most part too self-conscious,

self-sufficient, to ever quite attain.

Objectivity is the main characteristic of

contemporary naturalists, and this is true of the

portrait painters, the painters of genre and of

landscape. John S. Sargent is certainly one of

the great artists of all time. He has been likened

to Velasquez and the influence of that master is

indeed apparent. There is, however, in Sargent,

as in so many of his contemporaries, the display of

“bravura” in sheer pride of performance that one

never notices in

the more serious

art of the great

Spaniard. There

is more real affin-

ity to Hals,

whose impulsive

modeling by the

brush is at once

remembered,

also that swift

unhesitating

capture of the

first flash of im-

pression. Sar-

gent, it is true,

blurts out his

likes and dis-

likes, showing,

for example, the

dismal pride

that clings to

the fag ends of

ancient families

or ushering in

with mock dig-

nity the aristo-

his subjects in-

cracy of sudden wealth. When

terest him, as did Coventry Patmore and dear

little Beatrice Goelet, he makes them deeply

appealing. When, however, they bore or irritate

him, he attends to it that all who see his pic-

tures shall share his uncomplimentary impres-

sions. Yet he never paints what he does not

actually see. If there is a mask of false pretences

between him and his sitter he will not attempt to

penetrate it, choosing, rather, to paint it in with

particular care. This objectivity of vision is even

more a characteristic of our American landscape

painters, many of whom delight in the depiction

of the most uninteresting scenery. E. W. Red-

field paints little else than the slushy roads, the

cxxiv