Russian Art and American

reproduction of thought, life or emotion can but

admire Repin’s work. His industry also entitles

him to his rank. He made one hundred sketches

for the Cossacks, and painted three duplicates

of it. He tells the nature of the Cossacks as effec-

tively as his friend Tolstoi. Remorse he paints

adequately. Women have fainted at the sight of

his pictures. Ganz says, in “Russia of To-day ”:

“A youth of barely twenty-four had at one leap

placed himself at the head.” “Repin may be

compared, as a portrait painter, with the very

foremost artists of all times.” Our best critic says

of one of Repin’s pictures: “ It challenges compari-

son with the grim Spaniards at their best.”

Muther praises his work. There is little of the

“purple,” or the artificial, in Russian creations,

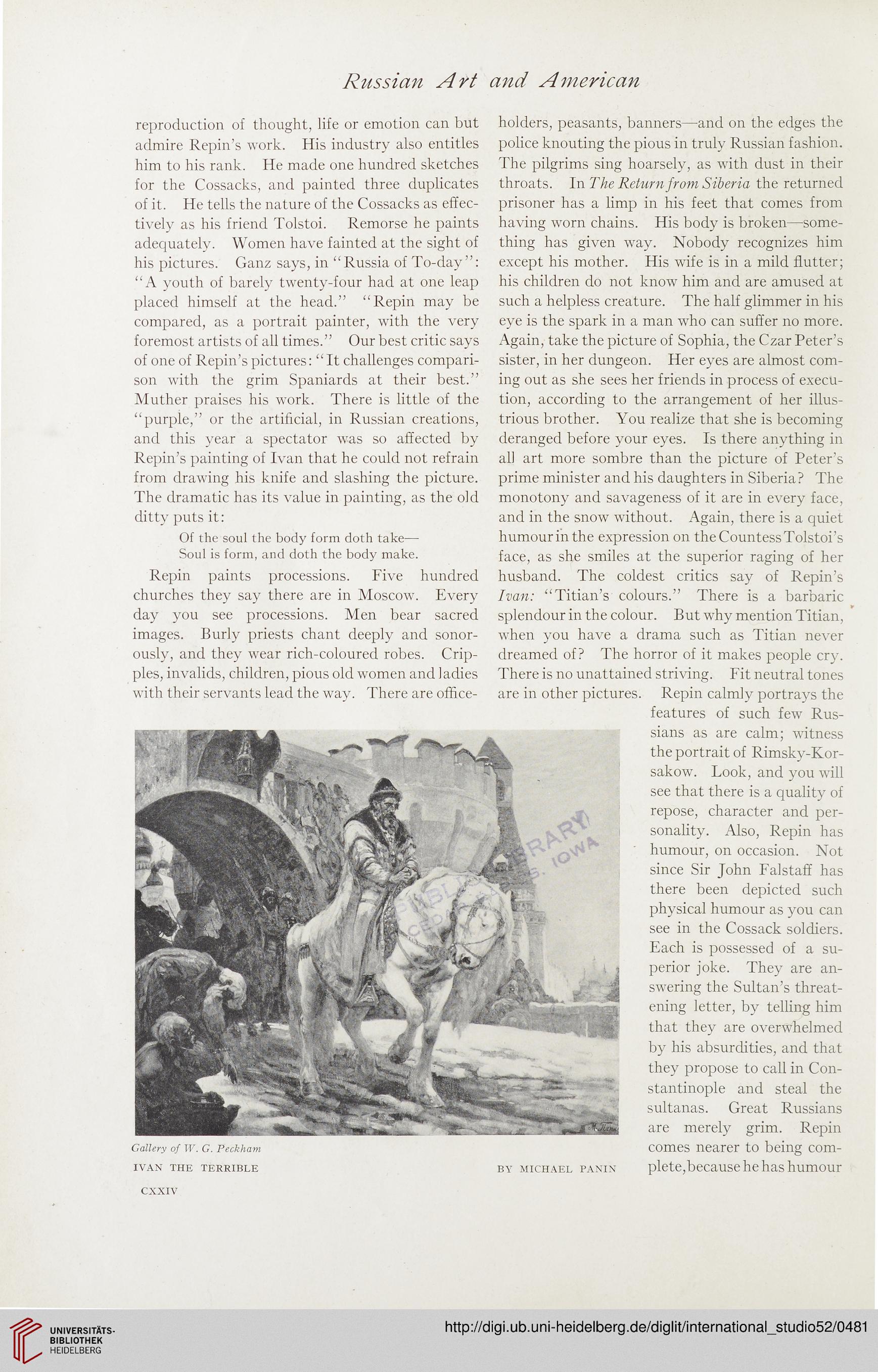

and this year a spectator was so affected by

Repin’s painting of Ivan that he could not refrain

from drawing his knife and slashing the picture.

The dramatic has its value in painting, as the old

ditty puts it:

Of the soul the body form doth take—

Soul is form, and doth the body make.

Repin paints processions. Five hundred

churches they say there are in Moscow. Every

day you see processions. Men bear sacred

images. Burly priests chant deeply and sonor-

ously, and they wear rich-coloured robes. Crip-

ples, invalids, children, pious old women and ladies

with their servants lead the way. There are office-

holders, peasants, banners—and on the edges the

police knouting the pious in truly Russian fashion.

The pilgrims sing hoarsely, as with dust in their

throats. In The Return from Siberia the returned

prisoner has a limp in his feet that comes from

having worn chains. His body is broken—some-

thing has given way. Nobody recognizes him

except his mother. His wife is in a mild flutter;

his children do not know him and are amused at

such a helpless creature. The half glimmer in his

eye is the spark in a man who can suffer no more.

Again, take the picture of Sophia, the Czar Peter’s

sister, in her dungeon. Her eyes are almost com-

ing out as she sees her friends in process of execu-

tion, according to the arrangement of her illus-

trious brother. You realize that she is becoming

deranged before your eyes. Is there anything in

all art more sombre than the picture of Peter’s

prime minister and his daughters in Siberia? The

monotony and savageness of it are in every face,

and in the snow without. Again, there is a quiet

humour in the expression on theCountessTolstoi’s

face, as she smiles at the superior raging of her

husband. The coldest critics say of Repin’s

Ivan: “Titian’s colours.” There is a barbaric

splendour in the colour. But why mention Titian,

when you have a drama such as Titian never

dreamed of? The horror of it makes people cry.

There is no unattained striving. Fit neutral tones

are in other pictures. Repin calmly portrays the

features of such few Rus-

sians as are calm; witness

the portrait of Rimsky-Kor-

sakow. Look, and you will

see that there is a quality of

repose, character and per-

sonality. Also, Repin has

humour, on occasion. Not

since Sir John Falstaff has

there been depicted such

physical humour as you can

see in the Cossack soldiers.

Each is possessed of a su-

perior joke. They are an-

swering the Sultan’s threat-

ening letter, by telling him

that they are overwhelmed

by his absurdities, and that

they propose to call in Con-

stantinople and steal the

sultanas. Great Russians

are merely grim. Repin

comes nearer to being com-

plete,because he has humour

Gallery of W. G. Peckham

IVAN THE TERRIBLE

BY MICHAEL PANIN

CXXIV

reproduction of thought, life or emotion can but

admire Repin’s work. His industry also entitles

him to his rank. He made one hundred sketches

for the Cossacks, and painted three duplicates

of it. He tells the nature of the Cossacks as effec-

tively as his friend Tolstoi. Remorse he paints

adequately. Women have fainted at the sight of

his pictures. Ganz says, in “Russia of To-day ”:

“A youth of barely twenty-four had at one leap

placed himself at the head.” “Repin may be

compared, as a portrait painter, with the very

foremost artists of all times.” Our best critic says

of one of Repin’s pictures: “ It challenges compari-

son with the grim Spaniards at their best.”

Muther praises his work. There is little of the

“purple,” or the artificial, in Russian creations,

and this year a spectator was so affected by

Repin’s painting of Ivan that he could not refrain

from drawing his knife and slashing the picture.

The dramatic has its value in painting, as the old

ditty puts it:

Of the soul the body form doth take—

Soul is form, and doth the body make.

Repin paints processions. Five hundred

churches they say there are in Moscow. Every

day you see processions. Men bear sacred

images. Burly priests chant deeply and sonor-

ously, and they wear rich-coloured robes. Crip-

ples, invalids, children, pious old women and ladies

with their servants lead the way. There are office-

holders, peasants, banners—and on the edges the

police knouting the pious in truly Russian fashion.

The pilgrims sing hoarsely, as with dust in their

throats. In The Return from Siberia the returned

prisoner has a limp in his feet that comes from

having worn chains. His body is broken—some-

thing has given way. Nobody recognizes him

except his mother. His wife is in a mild flutter;

his children do not know him and are amused at

such a helpless creature. The half glimmer in his

eye is the spark in a man who can suffer no more.

Again, take the picture of Sophia, the Czar Peter’s

sister, in her dungeon. Her eyes are almost com-

ing out as she sees her friends in process of execu-

tion, according to the arrangement of her illus-

trious brother. You realize that she is becoming

deranged before your eyes. Is there anything in

all art more sombre than the picture of Peter’s

prime minister and his daughters in Siberia? The

monotony and savageness of it are in every face,

and in the snow without. Again, there is a quiet

humour in the expression on theCountessTolstoi’s

face, as she smiles at the superior raging of her

husband. The coldest critics say of Repin’s

Ivan: “Titian’s colours.” There is a barbaric

splendour in the colour. But why mention Titian,

when you have a drama such as Titian never

dreamed of? The horror of it makes people cry.

There is no unattained striving. Fit neutral tones

are in other pictures. Repin calmly portrays the

features of such few Rus-

sians as are calm; witness

the portrait of Rimsky-Kor-

sakow. Look, and you will

see that there is a quality of

repose, character and per-

sonality. Also, Repin has

humour, on occasion. Not

since Sir John Falstaff has

there been depicted such

physical humour as you can

see in the Cossack soldiers.

Each is possessed of a su-

perior joke. They are an-

swering the Sultan’s threat-

ening letter, by telling him

that they are overwhelmed

by his absurdities, and that

they propose to call in Con-

stantinople and steal the

sultanas. Great Russians

are merely grim. Repin

comes nearer to being com-

plete,because he has humour

Gallery of W. G. Peckham

IVAN THE TERRIBLE

BY MICHAEL PANIN

CXXIV