Emile Clams

order once and for all to turn his boy from art,

decided to place him with a pastrycook; and here,

like Claude Lorrain, who also was a journeyman

baker, he distinguished himself by becoming

absorbed in the beauties of the landscape and

neglecting his business—so much so that ofttimes

he was heedless of the stealthy abstraction of his

wares by young rascals, enticed thereto by the

tempting dainties of his basket. Dismissed by his

employer, young Claus got work on the railway;

but fortunately Providence watches over those

whom she has impressed with the divine seal of

art, and it so happened that the famous musician,

Peter Benoit, being come to spend a few days of

his holidays with his father, a lock-keeper at Vive

St. Eloi, expressed his astonishment at finding

such an intelligent young man thwarted of his

proper vocation. He urged upon Emile’s father

that he should send his son to the Antwerp

Academy, persuading him that, apart from the

hours devoted to study, the lad might be able to

earn a little money. The father yielded to this

persuasion, and young Claus, having entered as a

student at the Academy, helped to maintain him-

self by working for a maker of devotional images.

As a student he made rapid progress, but despite

his academic successes, he became dissatisfied

with the usual routine, and finding a greater attrac-

tion in the busy scenes at the waterside soon

came to forsake the conventional subjects of the

Academy for those of everyday life. Ere long he

held an exhibition at Ghent, comprising genre

pictures, landscapes and a portrait of the sculptor

Joris, which aroused much comment.

By what curious coincidence can it have come

about that Emile Claus should have gone and

installed himself in the aforetime studio of Henri

de Braeckeleere, the father of modern luminists,

and this at an epoch when he had, as yet, not been

subjugated by the mysterious and powerful life of

light? Was it by reason of having dwelt within

those four walls wherein, as Camille Lemonnier

has said, Henri de Braekeleere “smote upon the

anvil the burning gold which spattered out in rosy

motes in the glowing atmosphere of Llhomme a la

fenetre, and L'homme as sis” that Claus, later on,

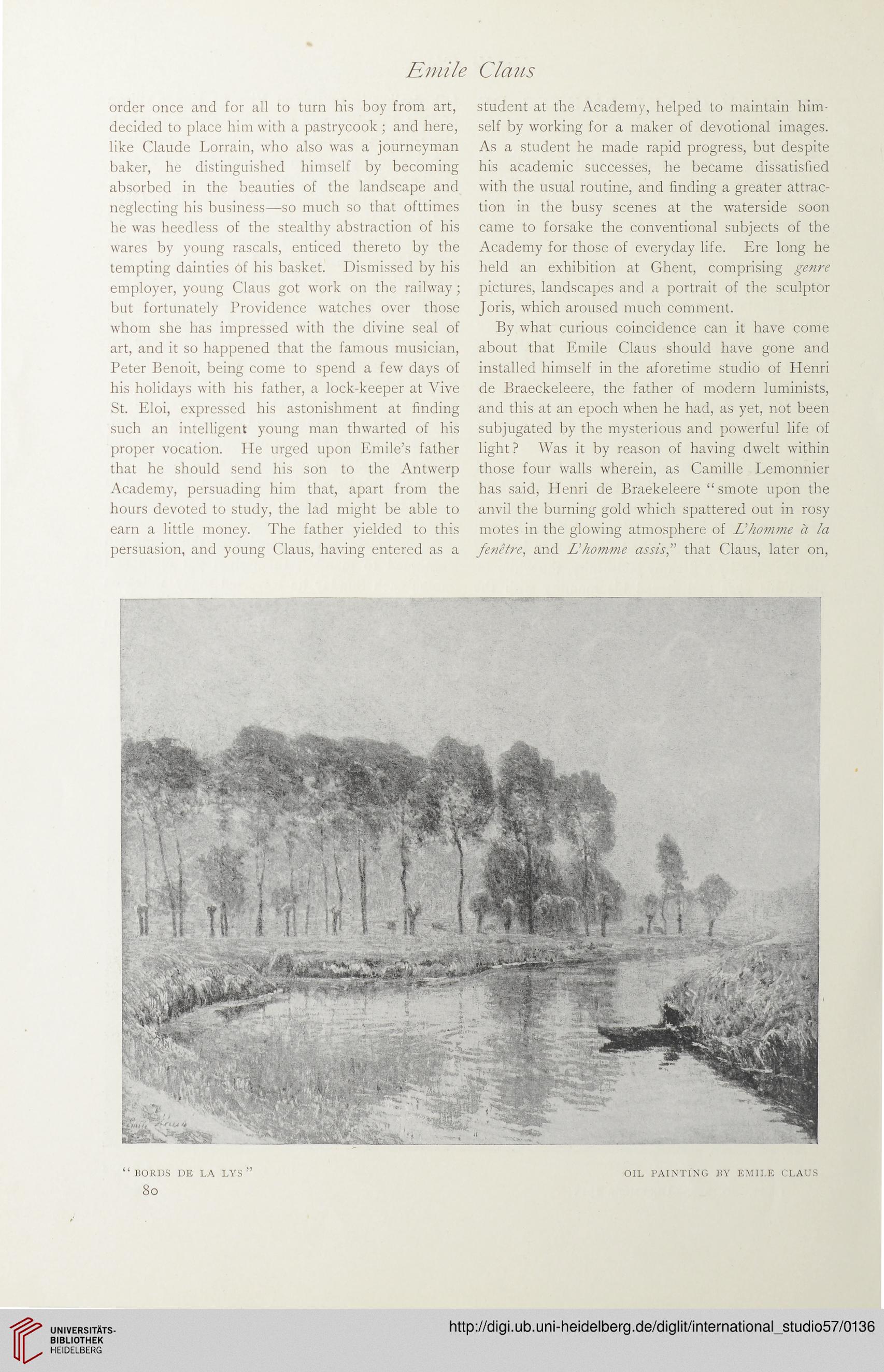

“ BORDS DE LA LYS”

8o

OIL PAINTING BY EMILE CLAUS

order once and for all to turn his boy from art,

decided to place him with a pastrycook; and here,

like Claude Lorrain, who also was a journeyman

baker, he distinguished himself by becoming

absorbed in the beauties of the landscape and

neglecting his business—so much so that ofttimes

he was heedless of the stealthy abstraction of his

wares by young rascals, enticed thereto by the

tempting dainties of his basket. Dismissed by his

employer, young Claus got work on the railway;

but fortunately Providence watches over those

whom she has impressed with the divine seal of

art, and it so happened that the famous musician,

Peter Benoit, being come to spend a few days of

his holidays with his father, a lock-keeper at Vive

St. Eloi, expressed his astonishment at finding

such an intelligent young man thwarted of his

proper vocation. He urged upon Emile’s father

that he should send his son to the Antwerp

Academy, persuading him that, apart from the

hours devoted to study, the lad might be able to

earn a little money. The father yielded to this

persuasion, and young Claus, having entered as a

student at the Academy, helped to maintain him-

self by working for a maker of devotional images.

As a student he made rapid progress, but despite

his academic successes, he became dissatisfied

with the usual routine, and finding a greater attrac-

tion in the busy scenes at the waterside soon

came to forsake the conventional subjects of the

Academy for those of everyday life. Ere long he

held an exhibition at Ghent, comprising genre

pictures, landscapes and a portrait of the sculptor

Joris, which aroused much comment.

By what curious coincidence can it have come

about that Emile Claus should have gone and

installed himself in the aforetime studio of Henri

de Braeckeleere, the father of modern luminists,

and this at an epoch when he had, as yet, not been

subjugated by the mysterious and powerful life of

light? Was it by reason of having dwelt within

those four walls wherein, as Camille Lemonnier

has said, Henri de Braekeleere “smote upon the

anvil the burning gold which spattered out in rosy

motes in the glowing atmosphere of Llhomme a la

fenetre, and L'homme as sis” that Claus, later on,

“ BORDS DE LA LYS”

8o

OIL PAINTING BY EMILE CLAUS