Paul Cezanne

Courtesy Montross Galleries

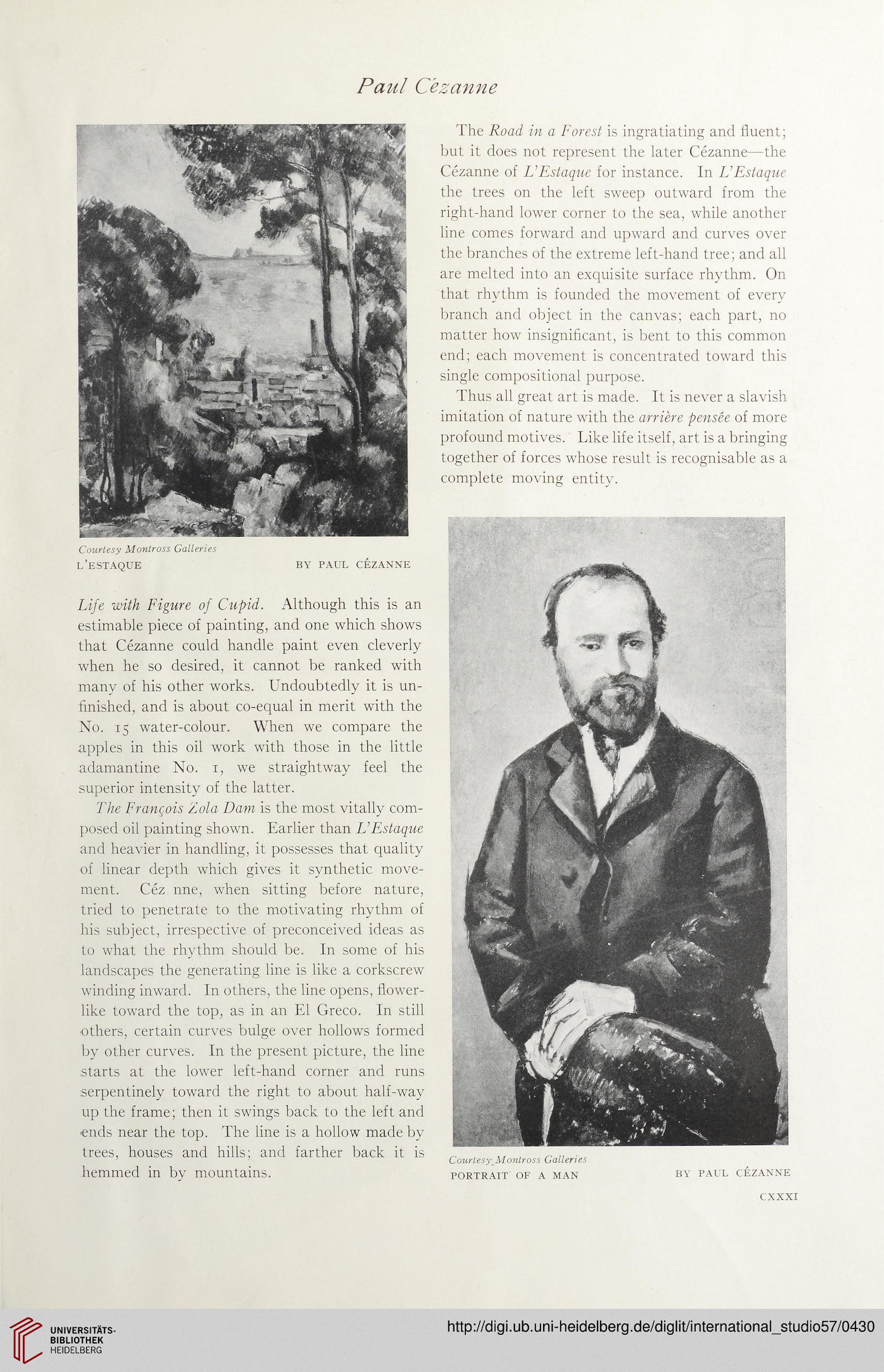

L’ESTAQUE BY PAUL CEZANNE

Life with Figure of Cupid. Although this is an

estimable piece of painting, and one which shows

that Cezanne could handle paint even cleverly

when he so desired, it cannot be ranked with

many of his other works. Undoubtedly it is un-

finished, and is about co-equal in merit with the

No. 15 water-colour. When we compare the

apples in this oil work with those in the little

adamantine No. 1, we straightway feel the

superior intensity of the latter.

The Francois Zola Dam is the most vitally com-

posed oil painting shown. Earlier than VEstaque

and heavier in handling, it possesses that quality

of linear depth which gives it synthetic move-

ment. Cez nne, when sitting before nature,

tried to penetrate to the motivating rhythm of

his subject, irrespective of preconceived ideas as

to what the rhythm should be. In some of his

landscapes the generating line is like a corkscrew

winding inward. In others, the line opens, flower-

like toward the top, as in an El Greco. In still

others, certain curves bulge over hollows formed

by other curves. In the present picture, the line

starts at the lower left-hand corner and runs

serpentinely toward the right to about half-way

up the frame; then it swings back to the left and

•ends near the top. The line is a hollow made by

trees, houses and hills; and farther back it is

hemmed in by mountains.

The Road in a Forest is ingratiating and fluent;

but it does not represent the later Cezanne—the

Cezanne of DEstaque for instance. In L’Estaque

the trees on the left sweep outward from the

right-hand lower corner to the sea, while another

line comes forward and upward and curves over

the branches of the extreme left-hand tree; and all

are melted into an exquisite surface rhythm. On

that rhythm is founded the movement of every

branch and object in the canvas; each part, no

matter how insignificant, is bent to this common

end; each movement is concentrated toward this

single compositional purpose.

Thus all great art is made. It is never a slavish

imitation of nature with the arriere pensee of more

profound motives. Like life itself, art is a bringing

together of forces whose result is recognisable as a

complete moving entity.

CourlesyMontross Galleries

PORTRAIT OF A MAN BY PAUL CEZANNE

CXXXI

Courtesy Montross Galleries

L’ESTAQUE BY PAUL CEZANNE

Life with Figure of Cupid. Although this is an

estimable piece of painting, and one which shows

that Cezanne could handle paint even cleverly

when he so desired, it cannot be ranked with

many of his other works. Undoubtedly it is un-

finished, and is about co-equal in merit with the

No. 15 water-colour. When we compare the

apples in this oil work with those in the little

adamantine No. 1, we straightway feel the

superior intensity of the latter.

The Francois Zola Dam is the most vitally com-

posed oil painting shown. Earlier than VEstaque

and heavier in handling, it possesses that quality

of linear depth which gives it synthetic move-

ment. Cez nne, when sitting before nature,

tried to penetrate to the motivating rhythm of

his subject, irrespective of preconceived ideas as

to what the rhythm should be. In some of his

landscapes the generating line is like a corkscrew

winding inward. In others, the line opens, flower-

like toward the top, as in an El Greco. In still

others, certain curves bulge over hollows formed

by other curves. In the present picture, the line

starts at the lower left-hand corner and runs

serpentinely toward the right to about half-way

up the frame; then it swings back to the left and

•ends near the top. The line is a hollow made by

trees, houses and hills; and farther back it is

hemmed in by mountains.

The Road in a Forest is ingratiating and fluent;

but it does not represent the later Cezanne—the

Cezanne of DEstaque for instance. In L’Estaque

the trees on the left sweep outward from the

right-hand lower corner to the sea, while another

line comes forward and upward and curves over

the branches of the extreme left-hand tree; and all

are melted into an exquisite surface rhythm. On

that rhythm is founded the movement of every

branch and object in the canvas; each part, no

matter how insignificant, is bent to this common

end; each movement is concentrated toward this

single compositional purpose.

Thus all great art is made. It is never a slavish

imitation of nature with the arriere pensee of more

profound motives. Like life itself, art is a bringing

together of forces whose result is recognisable as a

complete moving entity.

CourlesyMontross Galleries

PORTRAIT OF A MAN BY PAUL CEZANNE

CXXXI