painted in the sixteenth century, while the reverse with the Crucifbdon even up

to two hundred years later.13 However, in a subsequent publication he noted that

both icons could have been the creations of one workshop operating at the end

of the sixteenth century.14 Based on a thorough analysis of the style of a larger

representation, A. Tourta pushed back its dating to the second half of the fifteenth

century.15 Researchers also analysed iconography and composition,16 but little

space was devoted to the very act of inserting an older element into a newer one,

and turning it into an image within an image, therefore, it is worth focusing on

this aspect of the Vlatadon icon.

Icons upon icons versus icons within icons

Annemarie Weyl Carr pointed to the icon from Ylatadon as an example of dia-

logue between icons and their self-referential quality, manifested in the formation

of images showing other images, which are the most important element of the

representation, as is the case with the illustration of the Hamilton Psalter (see:

Figurę 4) or the icon of the Triumph of Orthodoxy (see: Figurę 5).17 The common-

alities between the icon from Ylatadon and the abovementioned examples include

similarity of composition, however, in the case of the Yladaton icon, the central

image is not a painted element, but one that has been physically inserted, therefore

it seems morę reasonable to compare it to other composite icons. In Ylatadon

itself there is another work reused in the same manner - by means of insertion.

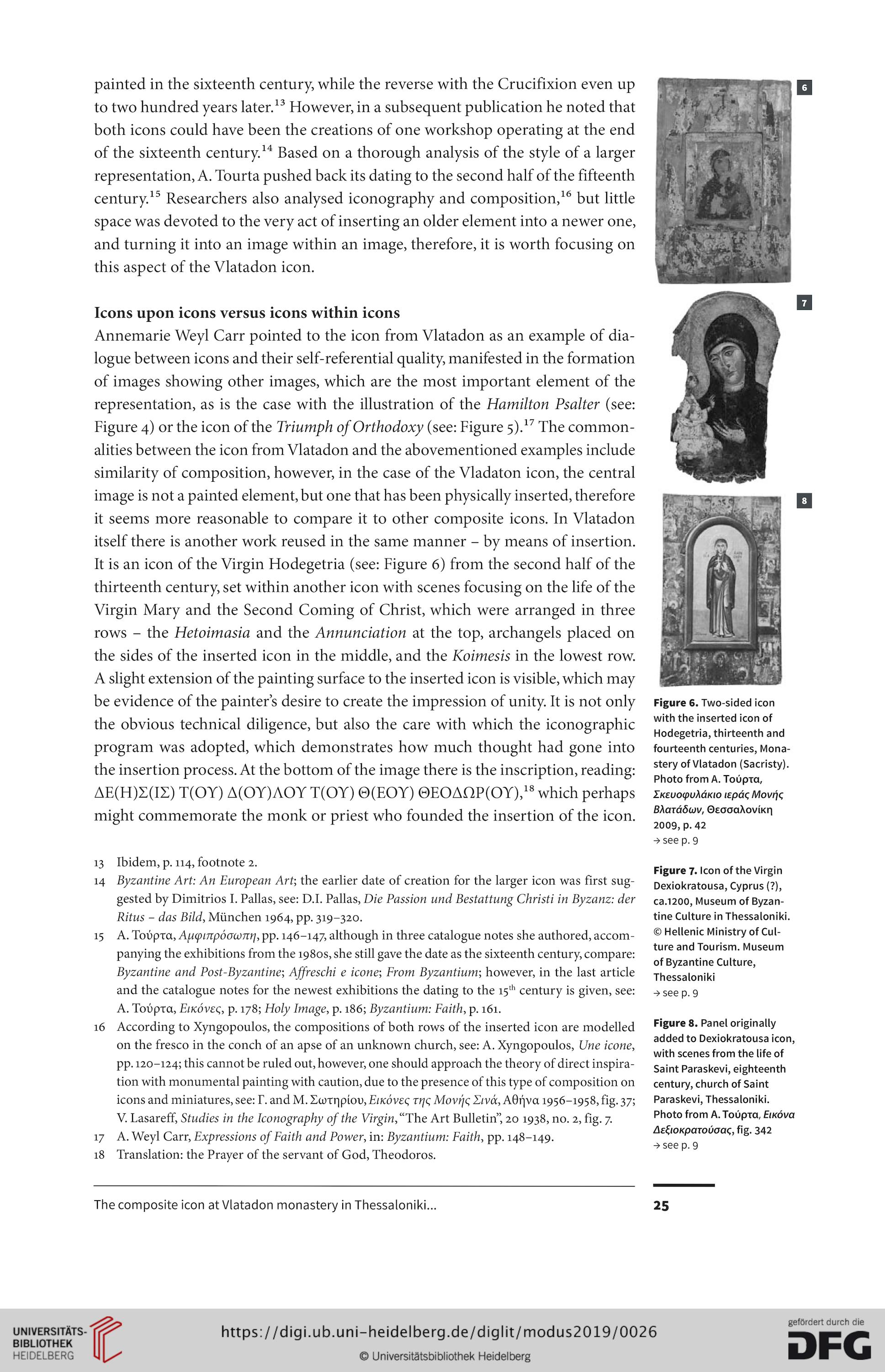

It is an icon of the Yirgin Hodegetria (see: Figurę 6) from the second half of the

thirteenth century, set within another icon with scenes focusing on the life of the

Yirgin Mary and the Second Corning of Christ, which were arranged in three

rows - the Hetoimasia and the Annunciation at the top, archangels placed on

the sides of the inserted icon in the middle, and the Koimesis in the lowest row.

A slight extension of the painting surface to the inserted icon is visible, which may

be evidence of the painter s desire to create the impression of unity. It is not only

the obvious technical diligence, but also the care with which the iconographic

program was adopted, which demonstrates how much thought had gone into

the insertion process. At the bottom of the image there is the inscription, reading:

AE(H)X(IX) T(OY) A(OY)AOY T(OY) 0(EOY) ©EOAOP(OY),18 which perhaps

might commemorate the monk or priest who founded the insertion of the icon.

13 Ibidem, p. 114, footnote 2.

14 Byzantine Art: An European Art; the earlier datę of creation for the larger icon was first sug-

gested by Dimitrios I. Pallas, see: D.I. Pallas, Die Passion und Bestattung Christi in Byzanz: der

Ritus - das Bild, Miinchen 1964, pp. 319-320.

15 A. Toupra, Apcpinpóaamrj, pp. 146-147, although in three catalogue notes she authored, accom-

panying the exhibitions from the 1980S, she still gave the datę as the sixteenth century, compare:

Byzantine and Post-Byzantine; Affreschi e icone; From Byzantium; however, in the last article

and the catalogue notes for the newest exhibitions the dating to the 15* century is given, see:

A. ToupTct, Eikóvec;, p. 178; Holy Image, p. 186; Byzantium: Faith, p. 161.

16 According to Xyngopoulos, the compositions of both rows of the inserted icon are modelled

on the fresco in the conch of an apse of an unknown church, see: A. Xyngopoulos, Une icone,

pp. 120-124; this cannot be ruled out, however, one should approach the theory of direct inspira-

tion with monumental painting with caution, due to the presence of this type of composition on

icons and miniatures, see: P. and M. Sarrr|piov,Eikóve(; rrjc, Movr/ę Eivd, A0qva 1956-1958, fig. 37;

V. Lasareff, Studies in the Iconography of the Yirgin, “The Art Bulletin”, 20 1938, no. 2, fig. 7.

17 A. Weyl Carr, Expressions of Faith and Power, in: Byzantium: Faith, pp. 148-149.

18 Translation: the Prayer of the servant of God, Theodoros.

Figurę 6. Two-sided icon

with the inserted icon of

Hodegetria, thirteenth and

fourteenth centuries, Mona-

stery of Vlatadon (Sacristy).

Photo from A. Toupra,

ŹKSuocpuhdKio lepaę Moviję

BAaraóww 0eooaXoviKr|

2009, p. 42

-> see p. 9

Figurę 7. Icon of the Virgin

Dexiokratousa, Cyprus (?),

ca.1200, Museum of Byzan-

tine Culture in Thessaloniki.

© Hellenie Ministry of Cul-

ture and Tourism. Museum

of Byzantine Culture,

Thessaloniki

-» see p. 9

Figurę 8. Panel originally

added to Dexiokratousa icon,

with scenes from the life of

Saint Paraskevi, eighteenth

century, church of Saint

Paraskevi, Thessaloniki.

Photo from A. Toupra, Eikóvo

AEŹioKpaTouoaę, fig. 342

->see p. 9

The composite icon at Vlatadon monastery in Thessaloniki...

25

to two hundred years later.13 However, in a subsequent publication he noted that

both icons could have been the creations of one workshop operating at the end

of the sixteenth century.14 Based on a thorough analysis of the style of a larger

representation, A. Tourta pushed back its dating to the second half of the fifteenth

century.15 Researchers also analysed iconography and composition,16 but little

space was devoted to the very act of inserting an older element into a newer one,

and turning it into an image within an image, therefore, it is worth focusing on

this aspect of the Vlatadon icon.

Icons upon icons versus icons within icons

Annemarie Weyl Carr pointed to the icon from Ylatadon as an example of dia-

logue between icons and their self-referential quality, manifested in the formation

of images showing other images, which are the most important element of the

representation, as is the case with the illustration of the Hamilton Psalter (see:

Figurę 4) or the icon of the Triumph of Orthodoxy (see: Figurę 5).17 The common-

alities between the icon from Ylatadon and the abovementioned examples include

similarity of composition, however, in the case of the Yladaton icon, the central

image is not a painted element, but one that has been physically inserted, therefore

it seems morę reasonable to compare it to other composite icons. In Ylatadon

itself there is another work reused in the same manner - by means of insertion.

It is an icon of the Yirgin Hodegetria (see: Figurę 6) from the second half of the

thirteenth century, set within another icon with scenes focusing on the life of the

Yirgin Mary and the Second Corning of Christ, which were arranged in three

rows - the Hetoimasia and the Annunciation at the top, archangels placed on

the sides of the inserted icon in the middle, and the Koimesis in the lowest row.

A slight extension of the painting surface to the inserted icon is visible, which may

be evidence of the painter s desire to create the impression of unity. It is not only

the obvious technical diligence, but also the care with which the iconographic

program was adopted, which demonstrates how much thought had gone into

the insertion process. At the bottom of the image there is the inscription, reading:

AE(H)X(IX) T(OY) A(OY)AOY T(OY) 0(EOY) ©EOAOP(OY),18 which perhaps

might commemorate the monk or priest who founded the insertion of the icon.

13 Ibidem, p. 114, footnote 2.

14 Byzantine Art: An European Art; the earlier datę of creation for the larger icon was first sug-

gested by Dimitrios I. Pallas, see: D.I. Pallas, Die Passion und Bestattung Christi in Byzanz: der

Ritus - das Bild, Miinchen 1964, pp. 319-320.

15 A. Toupra, Apcpinpóaamrj, pp. 146-147, although in three catalogue notes she authored, accom-

panying the exhibitions from the 1980S, she still gave the datę as the sixteenth century, compare:

Byzantine and Post-Byzantine; Affreschi e icone; From Byzantium; however, in the last article

and the catalogue notes for the newest exhibitions the dating to the 15* century is given, see:

A. ToupTct, Eikóvec;, p. 178; Holy Image, p. 186; Byzantium: Faith, p. 161.

16 According to Xyngopoulos, the compositions of both rows of the inserted icon are modelled

on the fresco in the conch of an apse of an unknown church, see: A. Xyngopoulos, Une icone,

pp. 120-124; this cannot be ruled out, however, one should approach the theory of direct inspira-

tion with monumental painting with caution, due to the presence of this type of composition on

icons and miniatures, see: P. and M. Sarrr|piov,Eikóve(; rrjc, Movr/ę Eivd, A0qva 1956-1958, fig. 37;

V. Lasareff, Studies in the Iconography of the Yirgin, “The Art Bulletin”, 20 1938, no. 2, fig. 7.

17 A. Weyl Carr, Expressions of Faith and Power, in: Byzantium: Faith, pp. 148-149.

18 Translation: the Prayer of the servant of God, Theodoros.

Figurę 6. Two-sided icon

with the inserted icon of

Hodegetria, thirteenth and

fourteenth centuries, Mona-

stery of Vlatadon (Sacristy).

Photo from A. Toupra,

ŹKSuocpuhdKio lepaę Moviję

BAaraóww 0eooaXoviKr|

2009, p. 42

-> see p. 9

Figurę 7. Icon of the Virgin

Dexiokratousa, Cyprus (?),

ca.1200, Museum of Byzan-

tine Culture in Thessaloniki.

© Hellenie Ministry of Cul-

ture and Tourism. Museum

of Byzantine Culture,

Thessaloniki

-» see p. 9

Figurę 8. Panel originally

added to Dexiokratousa icon,

with scenes from the life of

Saint Paraskevi, eighteenth

century, church of Saint

Paraskevi, Thessaloniki.

Photo from A. Toupra, Eikóvo

AEŹioKpaTouoaę, fig. 342

->see p. 9

The composite icon at Vlatadon monastery in Thessaloniki...

25