Sofia (see: Figurę 13), where the relief depiction of Saint George and Demetrius

was distinguished from the section with scenes of the saints lives using a very

wide frame with a floral ornament, imitating reliefs from the fourteenth century.27

The inserted element was also framed in a sixteenth-century icon from the Byz-

antine Museum in Athens (see: Figurę 14), where the lost image was replaced by

the Virgin of the Passion from the seventeenth century.28 Such a distinction can

also be found in the icon from the Panagia Chrysopolitissa church in Larnaca

(see: Figurę 15), where representations of prophets and hymnographers were added,

in the sixteenth century, to the image of the Virgin in an orans position with the

Child in a medallion.29 It seems that in all these examples, the smali element in

the form of a frame is meant to differentiate the inserted part. However, the element

in ąuestion also appears in other icons, which are not examples of composite icons,

as in the representation of Saint Nicholas enthroned and surrounded by scenes

from his life (see: Figurę 16). The whole is dated to around 1500, but the central

representation was framed with a convex frame, which creates an illusion of it

being a separate panel.30 It is possible that this is an example of imitation of com-

posite icons, resulting from the desire to raise the rank of the image by creating

the impression that the central representation is older. The above list of composite

icons illustrates a certain regularity, namely that in most of them the inserted ele-

ment is located in the central part of a larger representation, just like in the case

of the Vlatadon icon. In many cases, the older and the newer icons are separated

by a frame - which resulted not only in the enlargement of the icon, but above

all, in distinguishing the central work, prompting ąuestions about the potential

motives for this action.

The practice of insertion as “renovation”

It is highly probable that the insertion was intended to maintain the older work

in the best possible condition, whereas the enlargement should protect it from

destruction. The icons were never treated only in aesthetic terms - they were, and

so they still remain devotional images, which are considered sacred. Theologians

have often emphasized this - among them, Theodore the Studite, who in his Letter

to Platon of Sakkudion stressed that the essence of holiness in the icon does not

depend on the materiał, but on the holy prototype. When the image is destroyed, it

is not only the representation that is lost, but also its connection to the prototype,

and therefore its sanctity.31 The conseąuence of this relationship, and the depend-

ence of the copy on the original,32 was the special veneration attached to these

27 Various scholars datę the relief icon to the ioth, nth, or i2th, and the wooden icon, to the 14* or

15* century, respectively; see: K. Paskaleva, Die bulgarische Ikonę, Sofia 1981, p. 84.

28 M. AyeipauTou-tloTapidYoi), Eikóv£c; tov Bv^avrivov Movoeiov AQr[vó>v, A0r]va 1998, pp. 164-167,

no. 48.

29 Athanasions Papageorghiou refrained from proposing a datę of the inserted icon, and he only

stated that it was an earlier work; in turn, Kostas Papageorghiou in his publication mentions

the i4th century provenance, see: A. Papageorghiou, Icons of Cyprus, Nicosia 1992, p. 112, no. 69;

K. najiaYECopyiou, H EIavayia rrję Kvnpov — H SiKrjc; pac, FIavayia, Kunpoc; 2008, pp. 127-128.

30 From Byzantium, pp. 186-187,no. 57-

31 Theodori Studitae Epistulae, edited by G. Fatouros, Berolini-Novi Eboraci 1992 (= Corpus Fontium

Historiae Byzantinae: Series Berolinensis 31/1), pp. 164-168.

32 For a broader discussion, see: G. Babic, U modello e la replica nellarte bizantina delle icone, “Arte

Cristiana”,76,i988,pp. 62-78, particularlyp. 66; G.Yikan, Ruminations on Edible Icons: Originals

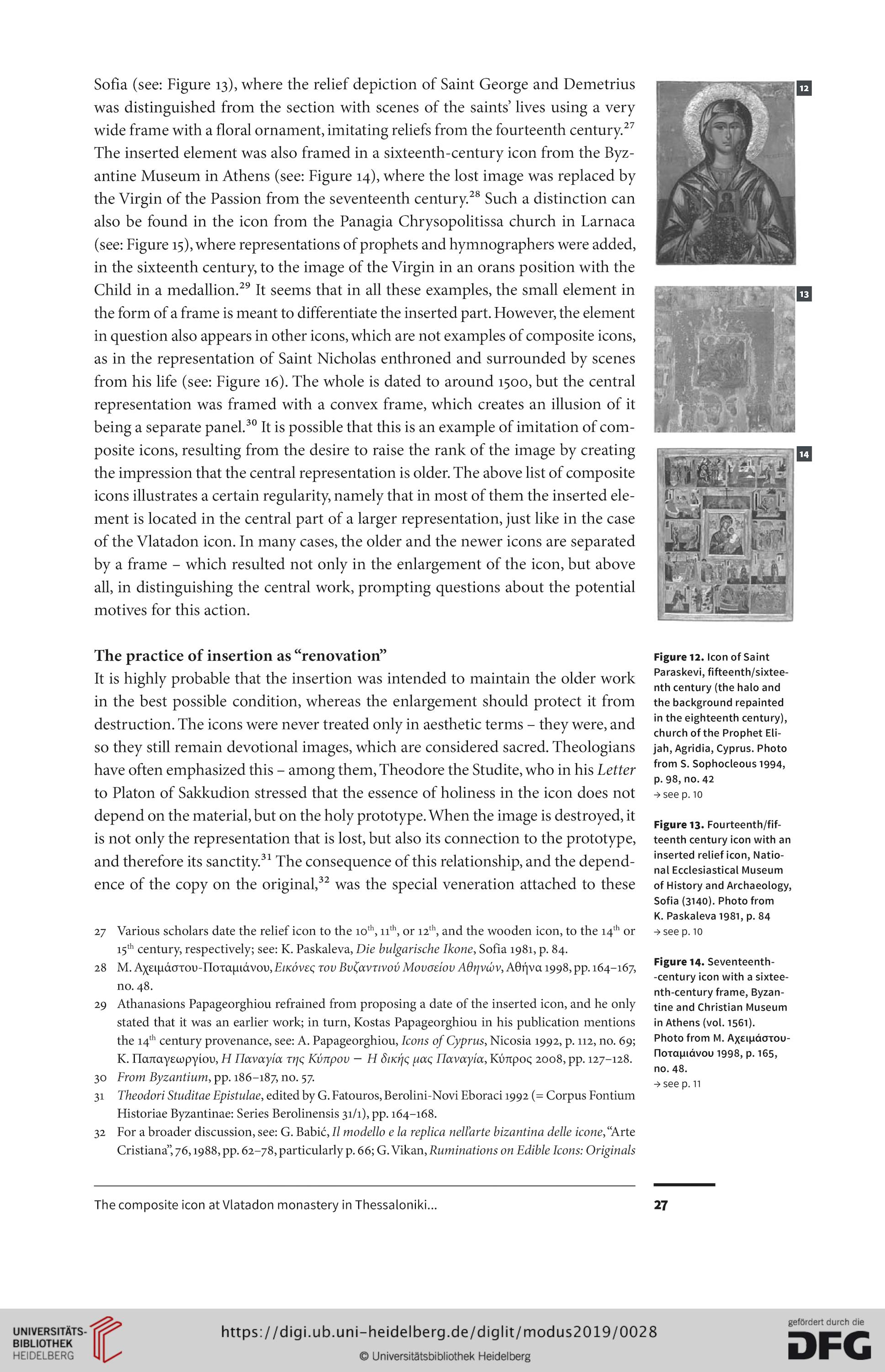

Figurę 12. Icon of Saint

Paraskevi, fifteenth/sixtee-

nth century (the halo and

the background repainted

in the eighteenth century),

church of the Prophet Eli-

jah, Agridia, Cyprus. Photo

from S. Sophocleous 1994,

p. 98, no. 42

-> see p. 10

Figurę 13. Fourteenth/fif-

teenth century icon with an

inserted relief icon, Natio-

nal Ecclesiastical Museum

of History and Archaeology,

Sofia (3140). Photo from

K. Paskaleva 1981, p. 84

-> see p. 10

Figurę 14. Seventeenth-

-century icon with a sixtee-

nth-century frame, Byzan-

tine and Christian Museum

in Athens (vol. 1561).

Photo from M. AycipóoTOU-

norcipićwou 1998, p. 165,

no. 48.

-> see p. n

27

The composite icon at Vlatadon monastery in Thessaloniki...

was distinguished from the section with scenes of the saints lives using a very

wide frame with a floral ornament, imitating reliefs from the fourteenth century.27

The inserted element was also framed in a sixteenth-century icon from the Byz-

antine Museum in Athens (see: Figurę 14), where the lost image was replaced by

the Virgin of the Passion from the seventeenth century.28 Such a distinction can

also be found in the icon from the Panagia Chrysopolitissa church in Larnaca

(see: Figurę 15), where representations of prophets and hymnographers were added,

in the sixteenth century, to the image of the Virgin in an orans position with the

Child in a medallion.29 It seems that in all these examples, the smali element in

the form of a frame is meant to differentiate the inserted part. However, the element

in ąuestion also appears in other icons, which are not examples of composite icons,

as in the representation of Saint Nicholas enthroned and surrounded by scenes

from his life (see: Figurę 16). The whole is dated to around 1500, but the central

representation was framed with a convex frame, which creates an illusion of it

being a separate panel.30 It is possible that this is an example of imitation of com-

posite icons, resulting from the desire to raise the rank of the image by creating

the impression that the central representation is older. The above list of composite

icons illustrates a certain regularity, namely that in most of them the inserted ele-

ment is located in the central part of a larger representation, just like in the case

of the Vlatadon icon. In many cases, the older and the newer icons are separated

by a frame - which resulted not only in the enlargement of the icon, but above

all, in distinguishing the central work, prompting ąuestions about the potential

motives for this action.

The practice of insertion as “renovation”

It is highly probable that the insertion was intended to maintain the older work

in the best possible condition, whereas the enlargement should protect it from

destruction. The icons were never treated only in aesthetic terms - they were, and

so they still remain devotional images, which are considered sacred. Theologians

have often emphasized this - among them, Theodore the Studite, who in his Letter

to Platon of Sakkudion stressed that the essence of holiness in the icon does not

depend on the materiał, but on the holy prototype. When the image is destroyed, it

is not only the representation that is lost, but also its connection to the prototype,

and therefore its sanctity.31 The conseąuence of this relationship, and the depend-

ence of the copy on the original,32 was the special veneration attached to these

27 Various scholars datę the relief icon to the ioth, nth, or i2th, and the wooden icon, to the 14* or

15* century, respectively; see: K. Paskaleva, Die bulgarische Ikonę, Sofia 1981, p. 84.

28 M. AyeipauTou-tloTapidYoi), Eikóv£c; tov Bv^avrivov Movoeiov AQr[vó>v, A0r]va 1998, pp. 164-167,

no. 48.

29 Athanasions Papageorghiou refrained from proposing a datę of the inserted icon, and he only

stated that it was an earlier work; in turn, Kostas Papageorghiou in his publication mentions

the i4th century provenance, see: A. Papageorghiou, Icons of Cyprus, Nicosia 1992, p. 112, no. 69;

K. najiaYECopyiou, H EIavayia rrję Kvnpov — H SiKrjc; pac, FIavayia, Kunpoc; 2008, pp. 127-128.

30 From Byzantium, pp. 186-187,no. 57-

31 Theodori Studitae Epistulae, edited by G. Fatouros, Berolini-Novi Eboraci 1992 (= Corpus Fontium

Historiae Byzantinae: Series Berolinensis 31/1), pp. 164-168.

32 For a broader discussion, see: G. Babic, U modello e la replica nellarte bizantina delle icone, “Arte

Cristiana”,76,i988,pp. 62-78, particularlyp. 66; G.Yikan, Ruminations on Edible Icons: Originals

Figurę 12. Icon of Saint

Paraskevi, fifteenth/sixtee-

nth century (the halo and

the background repainted

in the eighteenth century),

church of the Prophet Eli-

jah, Agridia, Cyprus. Photo

from S. Sophocleous 1994,

p. 98, no. 42

-> see p. 10

Figurę 13. Fourteenth/fif-

teenth century icon with an

inserted relief icon, Natio-

nal Ecclesiastical Museum

of History and Archaeology,

Sofia (3140). Photo from

K. Paskaleva 1981, p. 84

-> see p. 10

Figurę 14. Seventeenth-

-century icon with a sixtee-

nth-century frame, Byzan-

tine and Christian Museum

in Athens (vol. 1561).

Photo from M. AycipóoTOU-

norcipićwou 1998, p. 165,

no. 48.

-> see p. n

27

The composite icon at Vlatadon monastery in Thessaloniki...