October 5, 1867.] PUNCH, OR THE LONDON CHARIVARI.

133

!

THE ARREST OF SINALUNGA.

“ More in sorrow than in anger.”

Sad and yet stern, a firm but reverent hand

Italy lays upon her hero’s arm.

Whose love for her spurns Prudence’s command.

And sees in policy less help than harm.

In sorrow, not in wrath, she bids him pause,

Reminds him how e’en love law’s rule must own:

How subjects must be subjects, be their cause

The purest, holiest, e’er to patriot known.

With love that thus love’s urging countermands,

Patience that quenches Passion’s fev’rish fire,

She kisses, as she binds, the martyr’s hands,

Who for the cause would kindle his own pyre.

She honours her great prisoner, and his crime

Of love too eager, h'ope and faith too strong

To wait the mighty aids of Truth and Time—

Sure helps—if slow—whose work endureth long.

A EE AT FOR THE REFORM LEAGUE.

The Reform League, the other day, at the instance of

Mn. Reales, resolved on holding a meeting to express

their indignation at the arrest of Garibaldi. This demon-

stration will doubtless exert some influence on Louis

Napoleon, who has been the real cause of Garibaldi’s

arrest, by holding the Italian Government to the Sep-

tember Convention. With the view of compelling him to

release Victor-Emmanuel’s Cabinet from that compact,

the Reform League, with Beales at the head of them,

should go and hold their meeting on Garibaldi’s behalf

in the Tuileries Gardens. Such a demonstration under the

nose of the Emperor oe the French would not fail to

have a due effect upon him, particularly if its authors

threw down the Imperial railings.

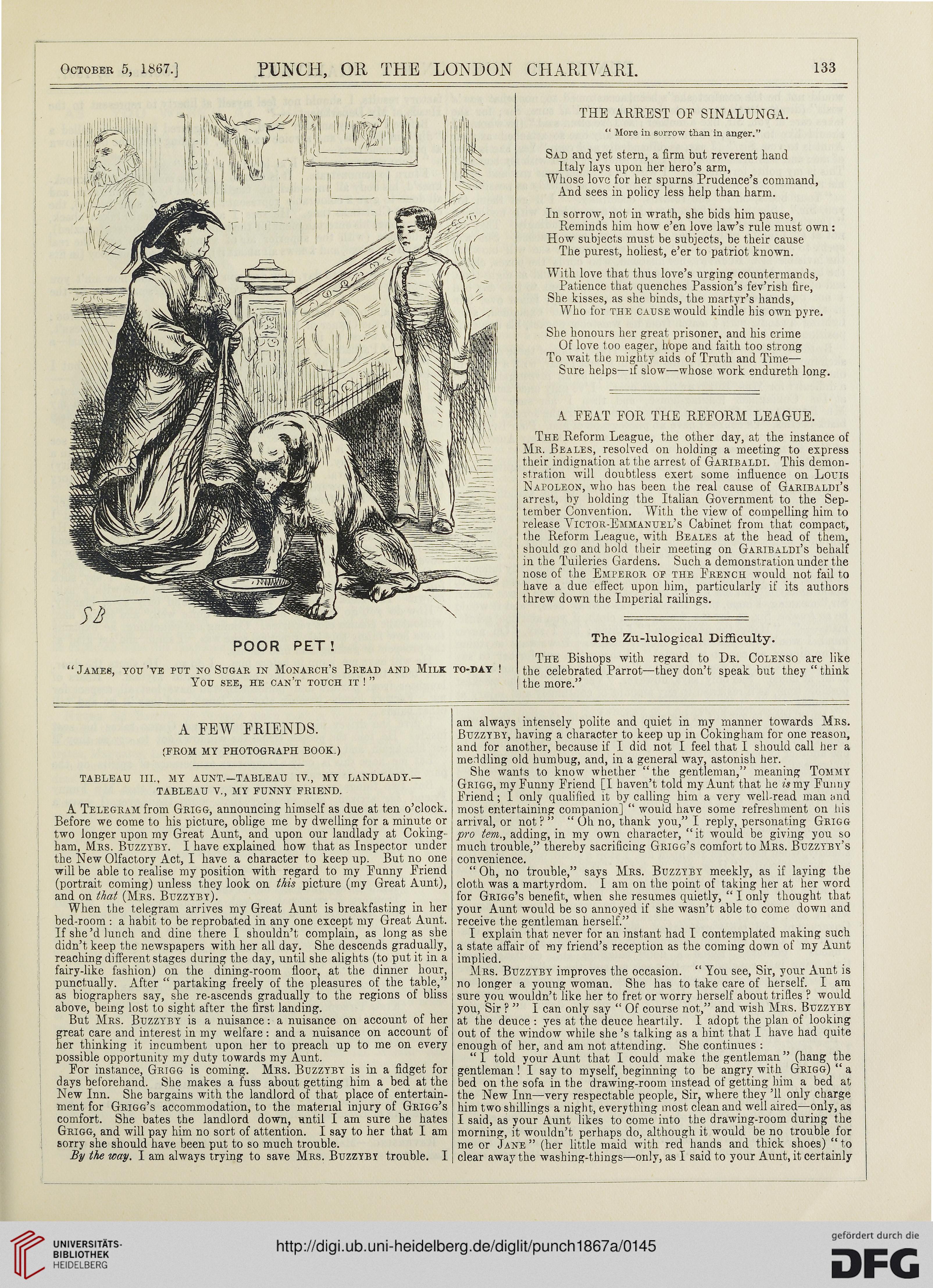

POOR PET!

“James, you’ve put no Sugar in Monarch’s Bread and Milk to-day !

You see, he can’t touch it ! ”

The Zu-lulogical Difficulty.

The Bishops with regard to Dr. Colenso are like

the celebrated Parrot—they don’t speak but they “ think

| the more.”

A LEW FRIENDS.

(FROM MY PHOTOGRAPH BOOK.)

TABLEAU III., MY AUNT.—TABLEAU IV., MY LANDLADY.—

TABLEAU V., MY FUNNY FRIEND.

A Telegram from Grigg, announcing himself as due at ten o’clock.

Before we come to his picture, oblige me by dwelling for a minute or

two longer upon my Great Aunt, and upon our landlady at Coking-

ham, Mrs. Buzzyby. I have explained how that as Inspector under

the New Olfactory Act, I have a character to keep up. But no one

will be able to realise my position with regard to my Funny Friend

(portrait coming) unless they look on this picture (my Great Aunt),

and on that (Mrs. Buzzyby).

When the telegram arrives my Great Aunt is breakfasting in her

bed-room : a habit to be reprobated in any one except my Great Aunt.

If she’d lunch and dine there I shouldn’t complain, as long as she

didn’t keep the newspapers with her all day. She descends gradually,

reaching different stages during the day, until she alights (to put it in a

fairy-like fashion) on the dining-room floor, at the dinner hour,

punctually. After “ partaking freely of the pleasures of the table,”

as biographers say, she re-ascends gradually to the regions of bliss

i above, being lost to sight after the first landing.

But Mrs. Buzzyby is a nuisance: a nuisance on account of her

great care and interest in my welfare : and a nuisance on account of

er thinking it incumbent upon her to preach up to me on every

possible opportunity my duty towards my Aunt.

For instance, Grigg is coming. Mrs. Buzzyby is in a fidget for

days beforehand. She makes a fuss about getting him a bed at the

New Inn. She bargains with the landlord of that place of entertain-

ment for Grigg’s accommodation, to the material injury of Grigg’s

comfort. She bates the landlord down, until I am sure he hates

Grigg, and will pay him no sort of attention. I say to her that I am

sorry she should have been put to so much trouble.

By the way. I am always trying to save Mrs. Buzzyby trouble. I

am always intensely polite and quiet in my manner towards Mrs.

Buzzyby, having a character to keep up in Cokingham for one reason,

and for another, because if I did not I feel that I should call her a

meddling old humbug, and, in a general way, astonish her.

She wants to know whether “the gentleman,” meaning Tommy

Grigg, my Funny Friend [I haven’t told my Aunt that he is my Funny

Friend; I only qualified it by calling him a very well-read man and

most entertaining companion] “ would have some refreshment on his

arrival, or not ? ” “ Oh no, thank you,” I reply, personating Grigg

pro tem., adding, in my own character, “it would be giving you so

much trouble,” thereby sacrificing Grigg’s comfort to Mrs. Buzzyby’s

convenience.

“ Oh, no trouble,” says Mrs. Buzzyby meekly, as if laying the

cloth was a martyrdom. I am on the point of taking her at her word

for Grigg’s benefit, when she resumes quietly, “ I only thought that

your Aunt would be so annoyed if she wasn’t able to come down and

receive the gentleman herself.”

I explain that never for an instant had I contemplated making such

a state affair of my friend’s reception as the coming down of my Aunt

implied.

Mrs. Buzzyby improves the occasion. “ You see, Sir, your Aunt is

no longer a young woman. She has to take care of herself. I am

sure you wouldn’t like her to fret or worry herself about trifles ? would

you, Sir ? ” I can only say “ Of course not,” and wish Mrs. Buzzyby

at the deuce : yes at the deuce heartily. I adopt the plan of looking

out of the window while she’s talking as a hint that I have had quite

enough of her, and am not attending. She continues :

“ I told your Aunt that I could make the gentleman ” (hang the

gentleman ! I say to myself, beginning to be angry with Grigg) “ a

bed on the sofa in the drawing-room instead of getting him a bed at

the New Inn—very respectable people. Sir, where they ’ll only charge

him two shillings a night, everything most clean and well aired—only, as

I said, as your Aunt likes to come into the drawing-room during the

morning, it wouldn’t perhaps do, although it would be no trouble^for

me or Jane ” (her little maid with red hands and thick shoes) “ to

clear away the washing-things—only, as I said to your Aunt, it certainly

133

!

THE ARREST OF SINALUNGA.

“ More in sorrow than in anger.”

Sad and yet stern, a firm but reverent hand

Italy lays upon her hero’s arm.

Whose love for her spurns Prudence’s command.

And sees in policy less help than harm.

In sorrow, not in wrath, she bids him pause,

Reminds him how e’en love law’s rule must own:

How subjects must be subjects, be their cause

The purest, holiest, e’er to patriot known.

With love that thus love’s urging countermands,

Patience that quenches Passion’s fev’rish fire,

She kisses, as she binds, the martyr’s hands,

Who for the cause would kindle his own pyre.

She honours her great prisoner, and his crime

Of love too eager, h'ope and faith too strong

To wait the mighty aids of Truth and Time—

Sure helps—if slow—whose work endureth long.

A EE AT FOR THE REFORM LEAGUE.

The Reform League, the other day, at the instance of

Mn. Reales, resolved on holding a meeting to express

their indignation at the arrest of Garibaldi. This demon-

stration will doubtless exert some influence on Louis

Napoleon, who has been the real cause of Garibaldi’s

arrest, by holding the Italian Government to the Sep-

tember Convention. With the view of compelling him to

release Victor-Emmanuel’s Cabinet from that compact,

the Reform League, with Beales at the head of them,

should go and hold their meeting on Garibaldi’s behalf

in the Tuileries Gardens. Such a demonstration under the

nose of the Emperor oe the French would not fail to

have a due effect upon him, particularly if its authors

threw down the Imperial railings.

POOR PET!

“James, you’ve put no Sugar in Monarch’s Bread and Milk to-day !

You see, he can’t touch it ! ”

The Zu-lulogical Difficulty.

The Bishops with regard to Dr. Colenso are like

the celebrated Parrot—they don’t speak but they “ think

| the more.”

A LEW FRIENDS.

(FROM MY PHOTOGRAPH BOOK.)

TABLEAU III., MY AUNT.—TABLEAU IV., MY LANDLADY.—

TABLEAU V., MY FUNNY FRIEND.

A Telegram from Grigg, announcing himself as due at ten o’clock.

Before we come to his picture, oblige me by dwelling for a minute or

two longer upon my Great Aunt, and upon our landlady at Coking-

ham, Mrs. Buzzyby. I have explained how that as Inspector under

the New Olfactory Act, I have a character to keep up. But no one

will be able to realise my position with regard to my Funny Friend

(portrait coming) unless they look on this picture (my Great Aunt),

and on that (Mrs. Buzzyby).

When the telegram arrives my Great Aunt is breakfasting in her

bed-room : a habit to be reprobated in any one except my Great Aunt.

If she’d lunch and dine there I shouldn’t complain, as long as she

didn’t keep the newspapers with her all day. She descends gradually,

reaching different stages during the day, until she alights (to put it in a

fairy-like fashion) on the dining-room floor, at the dinner hour,

punctually. After “ partaking freely of the pleasures of the table,”

as biographers say, she re-ascends gradually to the regions of bliss

i above, being lost to sight after the first landing.

But Mrs. Buzzyby is a nuisance: a nuisance on account of her

great care and interest in my welfare : and a nuisance on account of

er thinking it incumbent upon her to preach up to me on every

possible opportunity my duty towards my Aunt.

For instance, Grigg is coming. Mrs. Buzzyby is in a fidget for

days beforehand. She makes a fuss about getting him a bed at the

New Inn. She bargains with the landlord of that place of entertain-

ment for Grigg’s accommodation, to the material injury of Grigg’s

comfort. She bates the landlord down, until I am sure he hates

Grigg, and will pay him no sort of attention. I say to her that I am

sorry she should have been put to so much trouble.

By the way. I am always trying to save Mrs. Buzzyby trouble. I

am always intensely polite and quiet in my manner towards Mrs.

Buzzyby, having a character to keep up in Cokingham for one reason,

and for another, because if I did not I feel that I should call her a

meddling old humbug, and, in a general way, astonish her.

She wants to know whether “the gentleman,” meaning Tommy

Grigg, my Funny Friend [I haven’t told my Aunt that he is my Funny

Friend; I only qualified it by calling him a very well-read man and

most entertaining companion] “ would have some refreshment on his

arrival, or not ? ” “ Oh no, thank you,” I reply, personating Grigg

pro tem., adding, in my own character, “it would be giving you so

much trouble,” thereby sacrificing Grigg’s comfort to Mrs. Buzzyby’s

convenience.

“ Oh, no trouble,” says Mrs. Buzzyby meekly, as if laying the

cloth was a martyrdom. I am on the point of taking her at her word

for Grigg’s benefit, when she resumes quietly, “ I only thought that

your Aunt would be so annoyed if she wasn’t able to come down and

receive the gentleman herself.”

I explain that never for an instant had I contemplated making such

a state affair of my friend’s reception as the coming down of my Aunt

implied.

Mrs. Buzzyby improves the occasion. “ You see, Sir, your Aunt is

no longer a young woman. She has to take care of herself. I am

sure you wouldn’t like her to fret or worry herself about trifles ? would

you, Sir ? ” I can only say “ Of course not,” and wish Mrs. Buzzyby

at the deuce : yes at the deuce heartily. I adopt the plan of looking

out of the window while she’s talking as a hint that I have had quite

enough of her, and am not attending. She continues :

“ I told your Aunt that I could make the gentleman ” (hang the

gentleman ! I say to myself, beginning to be angry with Grigg) “ a

bed on the sofa in the drawing-room instead of getting him a bed at

the New Inn—very respectable people. Sir, where they ’ll only charge

him two shillings a night, everything most clean and well aired—only, as

I said, as your Aunt likes to come into the drawing-room during the

morning, it wouldn’t perhaps do, although it would be no trouble^for

me or Jane ” (her little maid with red hands and thick shoes) “ to

clear away the washing-things—only, as I said to your Aunt, it certainly