Lorenzo Lotto

During the rest of Lotto's life, from the National

Gallery double portrait of 1515 to the artist's

death in 1556, we are able to trace almost from

picture to picture a steady advance in expressiveness,

in which the means of expression went hand in

hand with the message he had to express. His

spirit shows itself sensitive, brooding, intensely

religious in a personal way, and full of sympathy

for all the more refined and subtle moods of the

human soul.

During his prime, from 1518 to 1528, when he

seems to have been happily situated in Bergamo,

Lotto's pictures have " an exuberance, a buoyancy,

a rush of life which find utterance in quick move-

ments, in an impatience of architectonic restraint,

in bold foreshortenings, and in brilliant, joyous

colouring .... but the psychological interest is

never absent, never wholly pushed out of sight by

the most joyous of feelings." In sacred subjects

as well as in portraits, " he seems never to have

painted without asking himself what effect a given

situation must have on a given character." Lotto

left Bergamo before he was fifty, and in the next

ten years attained some of his highest achievements

—" works retaining much of the health and blithe-

ness of the Bergamask time, but of larger scope

and deeper feeling." From the profoundly religious

spirit of many of these pictures Mr. Berenson

draws the inference, which appears to be well-

founded, that Lotto, during the repeated visits to

Venice which he is known to have made just at

this time, came into close contact with some of

the Italian Reformers who were then crowding

Venice. His biographer finds in this the explana-

tion of Lotto's suddenly deepened sense of religion,

and the almost evangelical familiarity with the

Bible displayed in his representations of sacred

events. In these, he goes on to say, "psychology

and personality mingle to a wonderful degree.

. . . . He interprets profoundly, and in his inter-

pretation expresses his own personality, showing

at a glance his attitude toward the whole of life."

These two notes—psychology and personality—

are, in fact, Lotto's distinguishing characteristics—

" a consciousness of self, a being aware at every

moment of what is going on within one's heart and

mind, a straining of the whole tangible universe

through the web of a sensitive personality.....

This makes him pre-eminently a psychologist, and

distinguishes him from such even of his con-

temporaries as are most like him: from Diirer,

who is near him in depth ; and from Correggio,

who comes close to him in sensitiveness. The most

constant attitude of Diirer's mind is moral earnest-

66

ness ; of Correggio's, rapturous emotion ; of Lotto's,

psychological interpretation—that is to say, interest

in the effect things have on the human conscious-

ness."

The pictures of Lotto's extreme old age, where,

as his physical energy flickered lower and lower, the

real fond of the man's nature appeared more and

more undisguised, do but deepen the impression

already received from the whole body of his work.

He remains to the last " a psychologist, using

psychology not for its own sake, but as an instru-

ment with which to give a finer interpretation of

character than was given by any of his contem-

poraries ; as a means of drawing closer to people,

of looking deeper down into their natures; as a

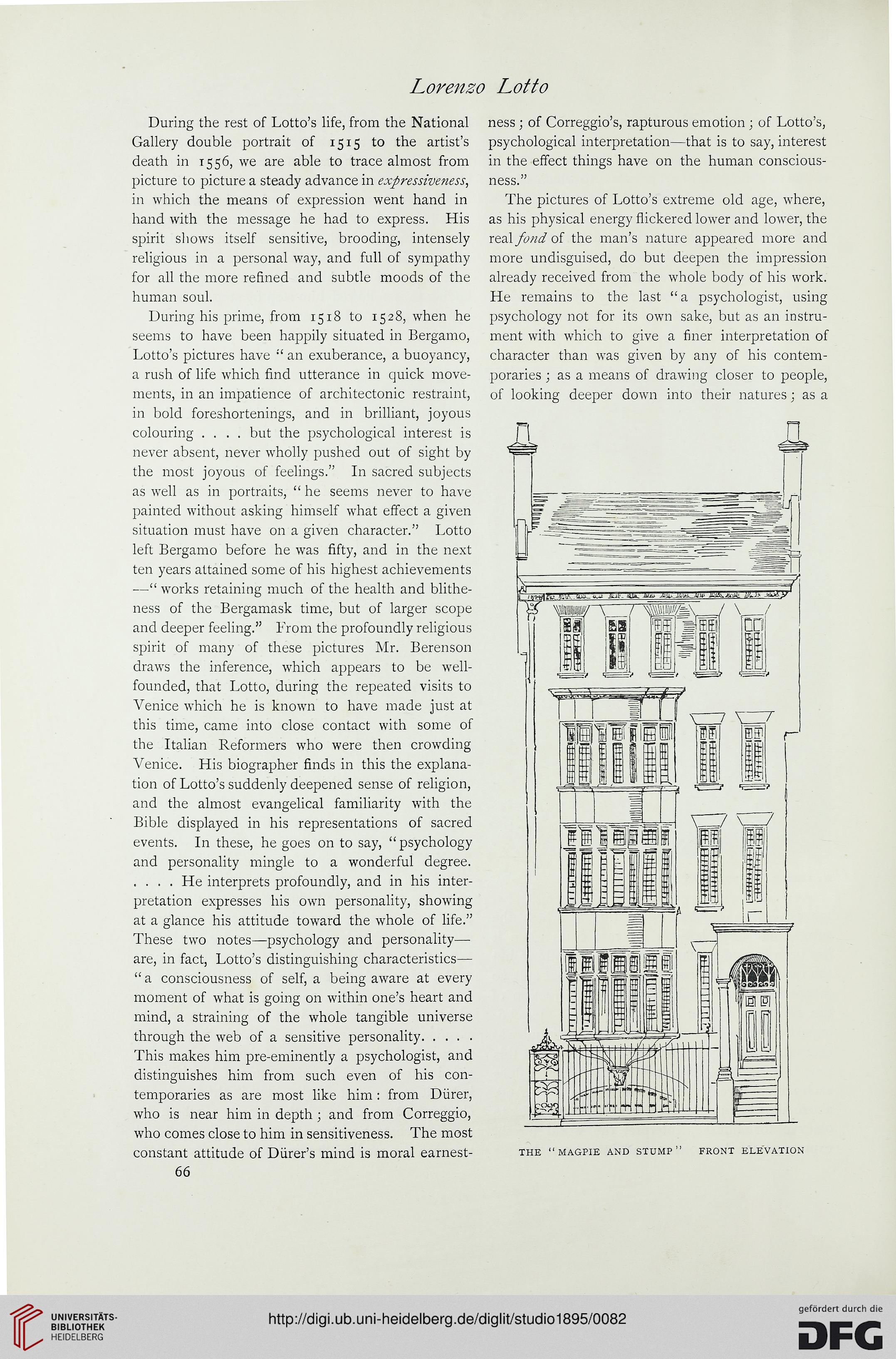

THE "MAGPIE AND STUMP " FRONT ELEVATION"

During the rest of Lotto's life, from the National

Gallery double portrait of 1515 to the artist's

death in 1556, we are able to trace almost from

picture to picture a steady advance in expressiveness,

in which the means of expression went hand in

hand with the message he had to express. His

spirit shows itself sensitive, brooding, intensely

religious in a personal way, and full of sympathy

for all the more refined and subtle moods of the

human soul.

During his prime, from 1518 to 1528, when he

seems to have been happily situated in Bergamo,

Lotto's pictures have " an exuberance, a buoyancy,

a rush of life which find utterance in quick move-

ments, in an impatience of architectonic restraint,

in bold foreshortenings, and in brilliant, joyous

colouring .... but the psychological interest is

never absent, never wholly pushed out of sight by

the most joyous of feelings." In sacred subjects

as well as in portraits, " he seems never to have

painted without asking himself what effect a given

situation must have on a given character." Lotto

left Bergamo before he was fifty, and in the next

ten years attained some of his highest achievements

—" works retaining much of the health and blithe-

ness of the Bergamask time, but of larger scope

and deeper feeling." From the profoundly religious

spirit of many of these pictures Mr. Berenson

draws the inference, which appears to be well-

founded, that Lotto, during the repeated visits to

Venice which he is known to have made just at

this time, came into close contact with some of

the Italian Reformers who were then crowding

Venice. His biographer finds in this the explana-

tion of Lotto's suddenly deepened sense of religion,

and the almost evangelical familiarity with the

Bible displayed in his representations of sacred

events. In these, he goes on to say, "psychology

and personality mingle to a wonderful degree.

. . . . He interprets profoundly, and in his inter-

pretation expresses his own personality, showing

at a glance his attitude toward the whole of life."

These two notes—psychology and personality—

are, in fact, Lotto's distinguishing characteristics—

" a consciousness of self, a being aware at every

moment of what is going on within one's heart and

mind, a straining of the whole tangible universe

through the web of a sensitive personality.....

This makes him pre-eminently a psychologist, and

distinguishes him from such even of his con-

temporaries as are most like him: from Diirer,

who is near him in depth ; and from Correggio,

who comes close to him in sensitiveness. The most

constant attitude of Diirer's mind is moral earnest-

66

ness ; of Correggio's, rapturous emotion ; of Lotto's,

psychological interpretation—that is to say, interest

in the effect things have on the human conscious-

ness."

The pictures of Lotto's extreme old age, where,

as his physical energy flickered lower and lower, the

real fond of the man's nature appeared more and

more undisguised, do but deepen the impression

already received from the whole body of his work.

He remains to the last " a psychologist, using

psychology not for its own sake, but as an instru-

ment with which to give a finer interpretation of

character than was given by any of his contem-

poraries ; as a means of drawing closer to people,

of looking deeper down into their natures; as a

THE "MAGPIE AND STUMP " FRONT ELEVATION"