Ringwood as a Sketching Ground

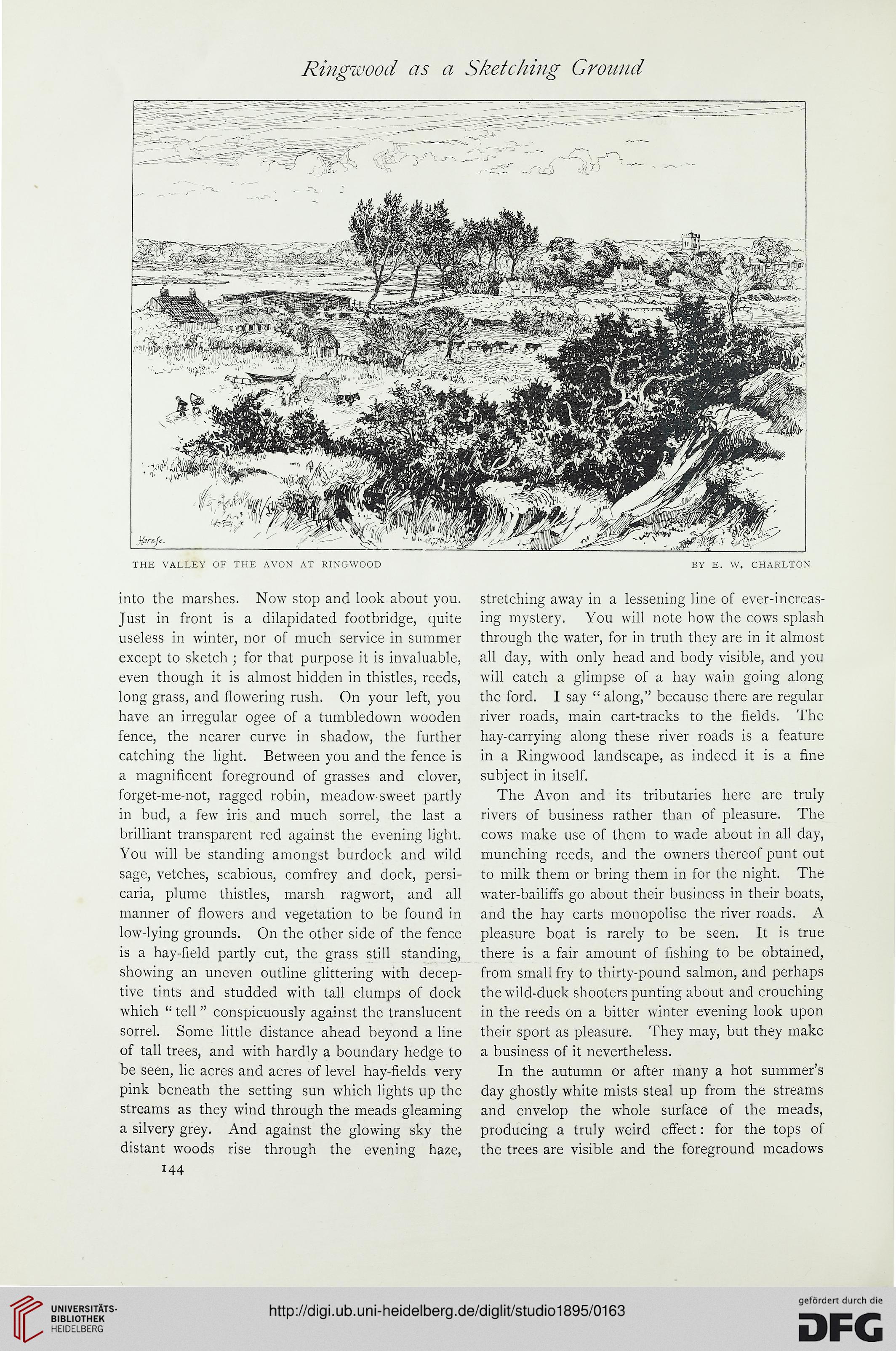

into the marshes. Now stop and look about you.

Just in front is a dilapidated footbridge, quite

useless in winter, nor of much service in summer

except to sketch ; for that purpose it is invaluable,

even though it is almost hidden in thistles, reeds,

long grass, and flowering rush. On your left, you

have an irregular ogee of a tumbledown wooden

fence, the nearer curve in shadow, the further

catching the light. Between you and the fence is

a magnificent foreground of grasses and clover,

forget-me-not, ragged robin, meadow sweet partly

in bud, a few iris and much sorrel, the last a

brilliant transparent red against the evening light.

You will be standing amongst burdock and wild

sage, vetches, scabious, comfrey and dock, persi-

caria, plume thistles, marsh ragwort, and all

manner of flowers and vegetation to be found in

low-lying grounds. On the other side of the fence

is a hay-field partly cut, the grass still standing,

showing an uneven outline glittering with decep-

tive tints and studded with tall clumps of dock

which " tell " conspicuously against the translucent

sorrel. Some little distance ahead beyond a line

of tall trees, and with hardly a boundary hedge to

be seen, lie acres and acres of level hay-fields very

pink beneath the setting sun which lights up the

streams as they wind through the meads gleaming

a silvery grey. And against the glowing sky the

distant woods rise through the evening haze,

144

stretching away in a lessening line of ever-increas-

ing mystery. You will note how the cows splash

through the water, for in truth they are in it almost

all day, with only head and body visible, and you

will catch a glimpse of a hay wain going along

the ford. I say " along," because there are regular

river roads, main cart-tracks to the fields. The

hay-carrying along these river roads is a feature

in a Ringwood landscape, as indeed it is a fine

subject in itself.

The Avon and its tributaries here are truly

rivers of business rather than of pleasure. The

cows make use of them to wade about in all day,

munching reeds, and the owners thereof punt out

to milk them or bring them in for the night. The

water-bailiffs go about their business in their boats,

and the hay carts monopolise the river roads. A

pleasure boat is rarely to be seen. It is true

there is a fair amount of fishing to be obtained,

from small fry to thirty-pound salmon, and perhaps

the wild-duck shooters punting about and crouching

in the reeds on a bitter winter evening look upon

their sport as pleasure. They may, but they make

a business of it nevertheless.

In the autumn or after many a hot summer's

day ghostly white mists steal up from the streams

and envelop the whole surface of the meads,

producing a truly weird effect: for the tops of

the trees are visible and the foreground meadows

into the marshes. Now stop and look about you.

Just in front is a dilapidated footbridge, quite

useless in winter, nor of much service in summer

except to sketch ; for that purpose it is invaluable,

even though it is almost hidden in thistles, reeds,

long grass, and flowering rush. On your left, you

have an irregular ogee of a tumbledown wooden

fence, the nearer curve in shadow, the further

catching the light. Between you and the fence is

a magnificent foreground of grasses and clover,

forget-me-not, ragged robin, meadow sweet partly

in bud, a few iris and much sorrel, the last a

brilliant transparent red against the evening light.

You will be standing amongst burdock and wild

sage, vetches, scabious, comfrey and dock, persi-

caria, plume thistles, marsh ragwort, and all

manner of flowers and vegetation to be found in

low-lying grounds. On the other side of the fence

is a hay-field partly cut, the grass still standing,

showing an uneven outline glittering with decep-

tive tints and studded with tall clumps of dock

which " tell " conspicuously against the translucent

sorrel. Some little distance ahead beyond a line

of tall trees, and with hardly a boundary hedge to

be seen, lie acres and acres of level hay-fields very

pink beneath the setting sun which lights up the

streams as they wind through the meads gleaming

a silvery grey. And against the glowing sky the

distant woods rise through the evening haze,

144

stretching away in a lessening line of ever-increas-

ing mystery. You will note how the cows splash

through the water, for in truth they are in it almost

all day, with only head and body visible, and you

will catch a glimpse of a hay wain going along

the ford. I say " along," because there are regular

river roads, main cart-tracks to the fields. The

hay-carrying along these river roads is a feature

in a Ringwood landscape, as indeed it is a fine

subject in itself.

The Avon and its tributaries here are truly

rivers of business rather than of pleasure. The

cows make use of them to wade about in all day,

munching reeds, and the owners thereof punt out

to milk them or bring them in for the night. The

water-bailiffs go about their business in their boats,

and the hay carts monopolise the river roads. A

pleasure boat is rarely to be seen. It is true

there is a fair amount of fishing to be obtained,

from small fry to thirty-pound salmon, and perhaps

the wild-duck shooters punting about and crouching

in the reeds on a bitter winter evening look upon

their sport as pleasure. They may, but they make

a business of it nevertheless.

In the autumn or after many a hot summer's

day ghostly white mists steal up from the streams

and envelop the whole surface of the meads,

producing a truly weird effect: for the tops of

the trees are visible and the foreground meadows