William Mouncey of Kirkcudbright

accepted with modesty the reputation which came

to him—a reputation that accrued to him as the

result of good work done, and not as the con-

sequence of the enthusiasm of indiscriminating

patrons or the subtle machinations of the log-

roller.

It has been said that Mouncey was self-taught.

It should also be added that he was quite impatient

of the irksomeness of routine teaching ; and that it

was as a matter of preference that he chose to experi-

ment, to develop along the lines he found possible to

himself, and to evolve, as far as he could, the methods

necessary for the attainment he desired. Whether,

if he had pursued a regular course of study in his

earlier years, he might have succeeded in doing more

than he did, is, of course, an insoluble question.

Certainly the handling that he adopted was large

and free—the rich impasto of brush work, the

use of the palette knife to place pigment on canvas,

even a squirt of pure colour from the tube, any-

thing was legitimate in his eyes so long as the

result he sought was obtained. But sometimes his

handling became meaningless, and smudge and

splash were more evident than skilled use of pig-

ment ; sometimes his inspiration failed him, and

then, ever a severe critic of his own work, he

would sacrifice the whole or any portion of a picture

that failed to please him, saving may be but a half

of the original work. And his massive use of paint,

effective and legitimate on large canvases, was out

of scale in his smaller works ; which, considered

simply as sketches, are fine and free, but which fail

to satisfy when criticised as completed pictures,

because the subject is overwhelmed by a dispropor-

tionate and insistent use of pigment.

The keynotes of Mouncey’s colour were mellow-

ness, sobriety and harmony. For a time the

brilliancy of tint that marked one phase of the art

of his fellow-townsman, Mr. Hornel, appealed to

him ; but this was really alien to his own ideals,

and he reverted to a palette that, while limited,

was both rich and delicate — a palette in

which golden and tawny hues were predominant.

Towards the end of his life, he used a fuller range

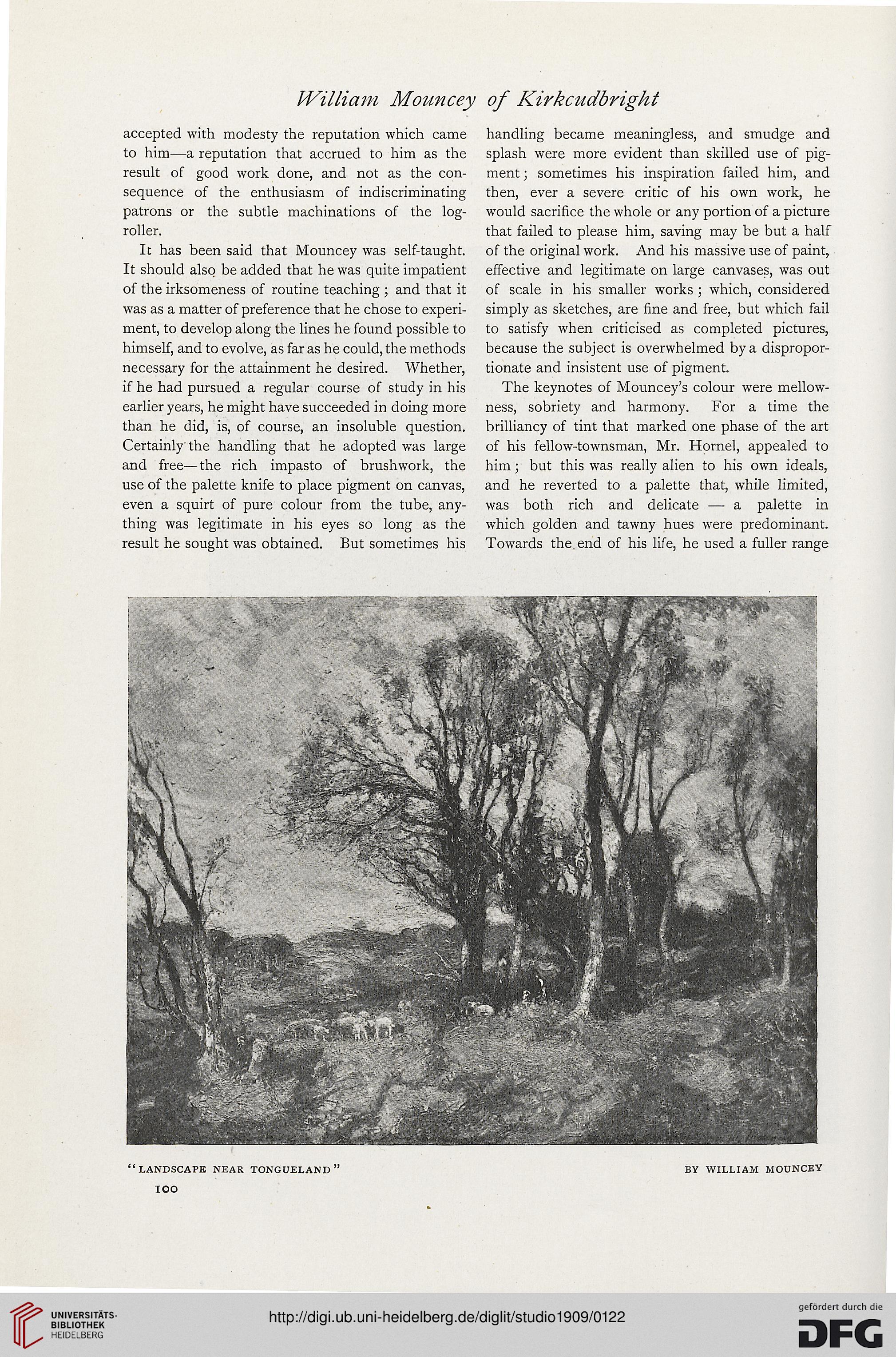

“landscape near tongueland”

BY WILLIAM MOUNCEY

TOO

accepted with modesty the reputation which came

to him—a reputation that accrued to him as the

result of good work done, and not as the con-

sequence of the enthusiasm of indiscriminating

patrons or the subtle machinations of the log-

roller.

It has been said that Mouncey was self-taught.

It should also be added that he was quite impatient

of the irksomeness of routine teaching ; and that it

was as a matter of preference that he chose to experi-

ment, to develop along the lines he found possible to

himself, and to evolve, as far as he could, the methods

necessary for the attainment he desired. Whether,

if he had pursued a regular course of study in his

earlier years, he might have succeeded in doing more

than he did, is, of course, an insoluble question.

Certainly the handling that he adopted was large

and free—the rich impasto of brush work, the

use of the palette knife to place pigment on canvas,

even a squirt of pure colour from the tube, any-

thing was legitimate in his eyes so long as the

result he sought was obtained. But sometimes his

handling became meaningless, and smudge and

splash were more evident than skilled use of pig-

ment ; sometimes his inspiration failed him, and

then, ever a severe critic of his own work, he

would sacrifice the whole or any portion of a picture

that failed to please him, saving may be but a half

of the original work. And his massive use of paint,

effective and legitimate on large canvases, was out

of scale in his smaller works ; which, considered

simply as sketches, are fine and free, but which fail

to satisfy when criticised as completed pictures,

because the subject is overwhelmed by a dispropor-

tionate and insistent use of pigment.

The keynotes of Mouncey’s colour were mellow-

ness, sobriety and harmony. For a time the

brilliancy of tint that marked one phase of the art

of his fellow-townsman, Mr. Hornel, appealed to

him ; but this was really alien to his own ideals,

and he reverted to a palette that, while limited,

was both rich and delicate — a palette in

which golden and tawny hues were predominant.

Towards the end of his life, he used a fuller range

“landscape near tongueland”

BY WILLIAM MOUNCEY

TOO