Studio-Talk

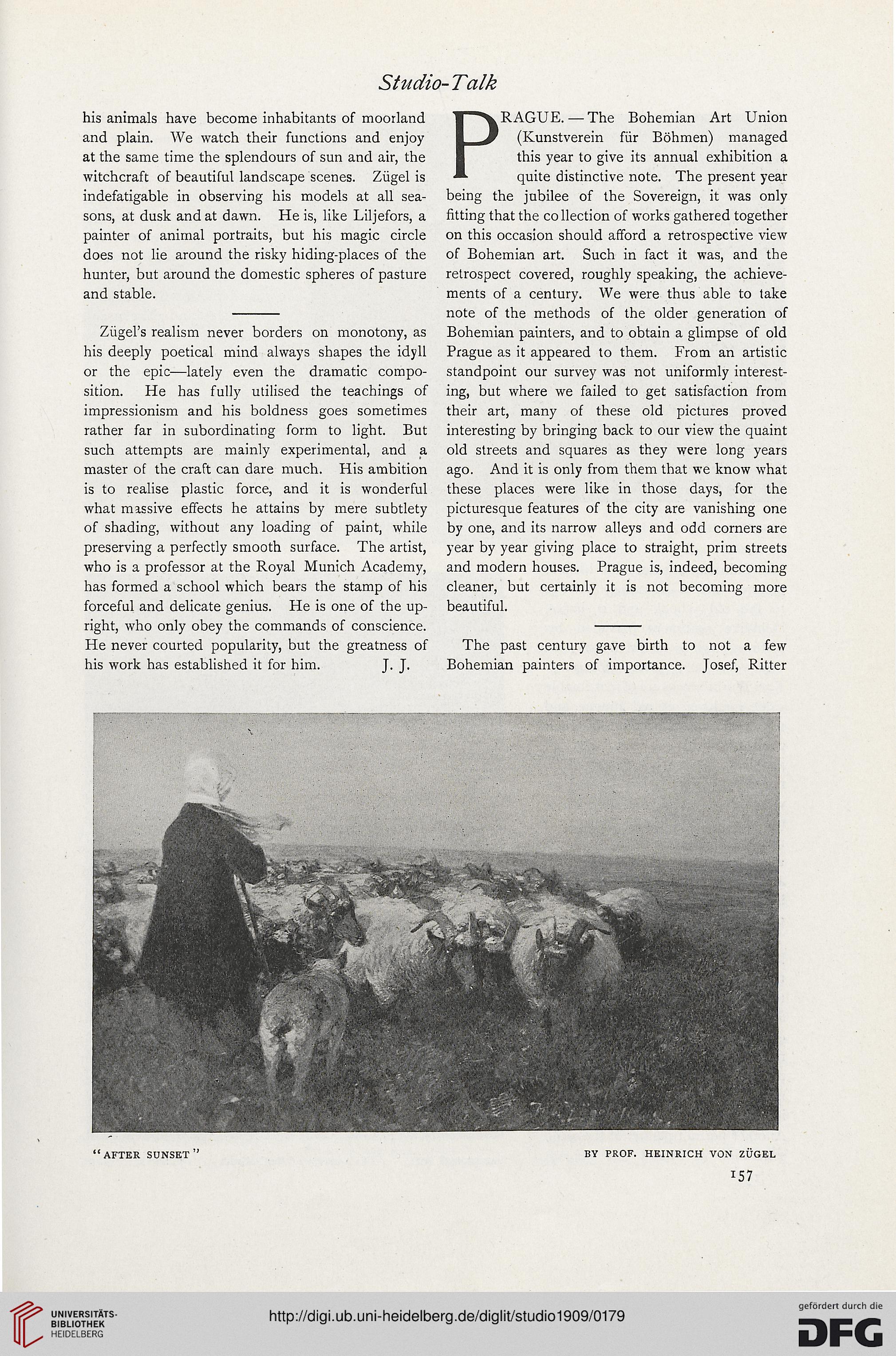

his animals have become inhabitants of moorland

and plain. We watch their functions and enjoy

at the same time the splendours of sun and air, the

witchcraft of beautiful landscape scenes. Zügel is

indefatigable in observing his models at all sea-

sons, at dusk and at dawn. He is, like Liljefors, a

painter of animal portraits, but his magic circle

does not lie around the risky hiding-places of the

hunter, but around the domestic spheres of pasture

and stable.

Zügel’s realism never borders on monotony, as

his deeply poetical mind always shapes the idyll

or the epic—lately even the dramatic compo-

sition. He has fully utilised the teachings of

impressionism and his boldness goes sometimes

rather far in subordinating form to light. But

such attempts are mainly experimental, and a

master of the craft can dare much. His ambition

is to realise plastic force, and it is wonderful

what massive effects he attains by mere subtlety

of shading, without any loading of paint, while

preserving a perfectly smooth surface. The artist,

who is a professor at the Royal Munich Academy,

has formed a school which bears the stamp of his

forceful and delicate genius. He is one of the up-

right, who only obey the commands of conscience.

He never courted popularity, but the greatness of

his work has established it for him. J. J.

PRAGUE. — The Bohemian Art Union

(Kunstverein für Böhmen) managed

this year to give its annual exhibition a

quite distinctive note. The present year

being the jubilee of the Sovereign, it was only

fitting that the collection of works gathered together

on this occasion should afford a retrospective view

of Bohemian art. Such in fact it was, and the

retrospect covered, roughly speaking, the achieve-

ments of a century. We were thus able to take

note of the methods of the older generation of

Bohemian painters, and to obtain a glimpse of old

Prague as it appeared to them. From an artistic

standpoint our survey was not uniformly interest-

ing, but where we failed to get satisfaction from

their art, many of these old pictures proved

interesting by bringing back to our view the quaint

old streets and squares as they were long years

ago. And it is only from them that we know what

these places were like in those days, for the

picturesque features of the city are vanishing one

by one, and its narrow alleys and odd corners are

year by year giving place to straight, prim streets

and modem houses. Prague is, indeed, becoming

cleaner, but certainly it is not becoming more

beautiful.

The past century gave birth to not a few

Bohemian painters of importance. Josef, Ritter

his animals have become inhabitants of moorland

and plain. We watch their functions and enjoy

at the same time the splendours of sun and air, the

witchcraft of beautiful landscape scenes. Zügel is

indefatigable in observing his models at all sea-

sons, at dusk and at dawn. He is, like Liljefors, a

painter of animal portraits, but his magic circle

does not lie around the risky hiding-places of the

hunter, but around the domestic spheres of pasture

and stable.

Zügel’s realism never borders on monotony, as

his deeply poetical mind always shapes the idyll

or the epic—lately even the dramatic compo-

sition. He has fully utilised the teachings of

impressionism and his boldness goes sometimes

rather far in subordinating form to light. But

such attempts are mainly experimental, and a

master of the craft can dare much. His ambition

is to realise plastic force, and it is wonderful

what massive effects he attains by mere subtlety

of shading, without any loading of paint, while

preserving a perfectly smooth surface. The artist,

who is a professor at the Royal Munich Academy,

has formed a school which bears the stamp of his

forceful and delicate genius. He is one of the up-

right, who only obey the commands of conscience.

He never courted popularity, but the greatness of

his work has established it for him. J. J.

PRAGUE. — The Bohemian Art Union

(Kunstverein für Böhmen) managed

this year to give its annual exhibition a

quite distinctive note. The present year

being the jubilee of the Sovereign, it was only

fitting that the collection of works gathered together

on this occasion should afford a retrospective view

of Bohemian art. Such in fact it was, and the

retrospect covered, roughly speaking, the achieve-

ments of a century. We were thus able to take

note of the methods of the older generation of

Bohemian painters, and to obtain a glimpse of old

Prague as it appeared to them. From an artistic

standpoint our survey was not uniformly interest-

ing, but where we failed to get satisfaction from

their art, many of these old pictures proved

interesting by bringing back to our view the quaint

old streets and squares as they were long years

ago. And it is only from them that we know what

these places were like in those days, for the

picturesque features of the city are vanishing one

by one, and its narrow alleys and odd corners are

year by year giving place to straight, prim streets

and modem houses. Prague is, indeed, becoming

cleaner, but certainly it is not becoming more

beautiful.

The past century gave birth to not a few

Bohemian painters of importance. Josef, Ritter