Architectural Gardening.—III.

burgh, Norfolk, on page 184, and the house and

garden plan on page 186, for a site near Sherborne,

in Dorset, the accompanying designs have been

made with no such restrictions, either of site or

space, except that bounded by the paper on which

they are drawn. These designs, therefore, are to

be considered less as projects in practical building

than as efforts in pictorial design. In each case,

however, some idea, more or less nebulous, has been

sketched out beforehand, so that each detail, as here

illustrated, has some relation or connection with

other portions of an entire scheme. In other words,

nothing is shown in any of these designs which

could not be carried out in actual practice.

They are intended to embody and illustrate some

of the principles of architectural gardening as applied

to its design. Something of the effect wrought by

the hand of Time upon such work has been anti-

cipated in some of these drawings, not only for the

sake of pictorial effect, but also because new houses

and gardens, whatever their merits, cannot possess

the same charm that comes with age or long use.

Most of the so-called landscape gardens now

existing are of a respectable age, and just so far as

time and use have helped them, they gain accord-

ingly in comparison with the newer gardens of the

formal manner. In this way they claim a merit

which is in fact no inherent part

of the design.

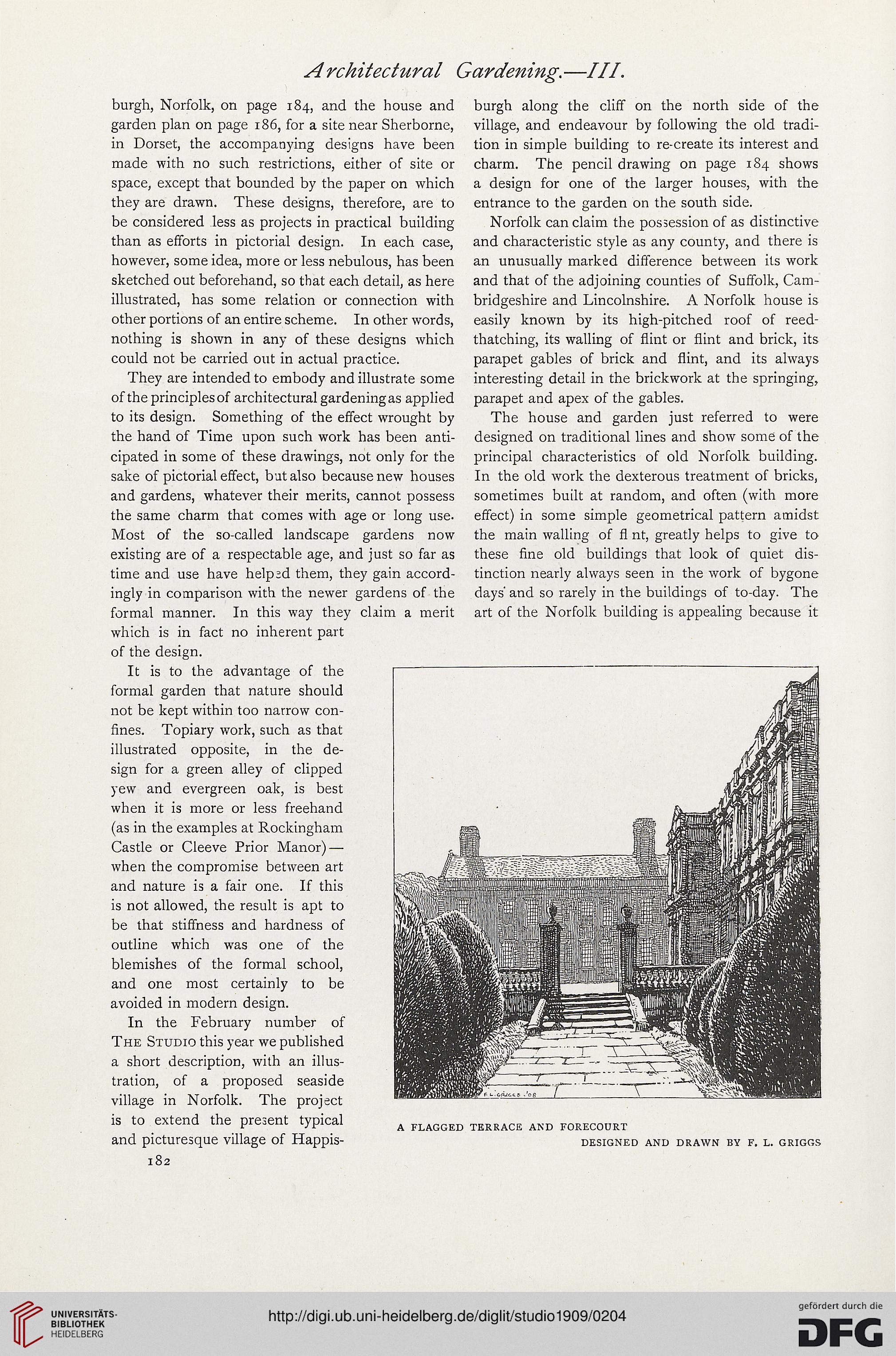

It is to the advantage of the

formal garden that nature should

not be kept within too narrow con-

fines. Topiary work, such as that

illustrated opposite, in the de-

sign for a green alley of clipped

yew and evergreen oak, is best

when it is more or less freehand

(as in the examples at Rockingham

Castle or Cleeve Prior Manor) —

when the compromise between art

and nature is a fair one. If this

is not allowed, the result is apt to

be that stiffness and hardness of

outline which was one of the

blemishes of the formal school,

and one most certainly to be

avoided in modern design.

In the February number of

The Studio this year we published

a short description, with an illus-

tration, of a proposed seaside

village in Norfolk. The project

is to extend the present typical

and picturesque village of Happis-

182

burgh along the cliff on the north side of the

village, and endeavour by following the old tradi-

tion in simple building to re-create its interest and

charm. The pencil drawing on page 184 shows

a design for one of the larger houses, with the

entrance to the garden on the south side.

Norfolk can claim the possession of as distinctive

and characteristic style as any county, and there is

an unusually marked difference between its work

and that of the adjoining counties of Suffolk, Cam-

bridgeshire and Lincolnshire. A Norfolk house is

easily known by its high-pitched roof of reed-

thatching, its walling of flint or flint and brick, its

parapet gables of brick and flint, and its always

interesting detail in the brickwork at the springing,

parapet and apex of the gables.

The house and garden just referred to were

designed on traditional lines and show some of the

principal characteristics of old Norfolk building.

In the old work the dexterous treatment of bricks,

sometimes built at random, and often (with more

effect) in some simple geometrical pattern amidst

the main walling of fl nt, greatly helps to give to

these fine old buildings that look of quiet dis-

tinction nearly always seen in the work of bygone

days' and so rarely in the buildings of to-day. The

art of the Norfolk building is appealing because it

DESIGNED AND DRAWN BY F. L. GRIGGS

burgh, Norfolk, on page 184, and the house and

garden plan on page 186, for a site near Sherborne,

in Dorset, the accompanying designs have been

made with no such restrictions, either of site or

space, except that bounded by the paper on which

they are drawn. These designs, therefore, are to

be considered less as projects in practical building

than as efforts in pictorial design. In each case,

however, some idea, more or less nebulous, has been

sketched out beforehand, so that each detail, as here

illustrated, has some relation or connection with

other portions of an entire scheme. In other words,

nothing is shown in any of these designs which

could not be carried out in actual practice.

They are intended to embody and illustrate some

of the principles of architectural gardening as applied

to its design. Something of the effect wrought by

the hand of Time upon such work has been anti-

cipated in some of these drawings, not only for the

sake of pictorial effect, but also because new houses

and gardens, whatever their merits, cannot possess

the same charm that comes with age or long use.

Most of the so-called landscape gardens now

existing are of a respectable age, and just so far as

time and use have helped them, they gain accord-

ingly in comparison with the newer gardens of the

formal manner. In this way they claim a merit

which is in fact no inherent part

of the design.

It is to the advantage of the

formal garden that nature should

not be kept within too narrow con-

fines. Topiary work, such as that

illustrated opposite, in the de-

sign for a green alley of clipped

yew and evergreen oak, is best

when it is more or less freehand

(as in the examples at Rockingham

Castle or Cleeve Prior Manor) —

when the compromise between art

and nature is a fair one. If this

is not allowed, the result is apt to

be that stiffness and hardness of

outline which was one of the

blemishes of the formal school,

and one most certainly to be

avoided in modern design.

In the February number of

The Studio this year we published

a short description, with an illus-

tration, of a proposed seaside

village in Norfolk. The project

is to extend the present typical

and picturesque village of Happis-

182

burgh along the cliff on the north side of the

village, and endeavour by following the old tradi-

tion in simple building to re-create its interest and

charm. The pencil drawing on page 184 shows

a design for one of the larger houses, with the

entrance to the garden on the south side.

Norfolk can claim the possession of as distinctive

and characteristic style as any county, and there is

an unusually marked difference between its work

and that of the adjoining counties of Suffolk, Cam-

bridgeshire and Lincolnshire. A Norfolk house is

easily known by its high-pitched roof of reed-

thatching, its walling of flint or flint and brick, its

parapet gables of brick and flint, and its always

interesting detail in the brickwork at the springing,

parapet and apex of the gables.

The house and garden just referred to were

designed on traditional lines and show some of the

principal characteristics of old Norfolk building.

In the old work the dexterous treatment of bricks,

sometimes built at random, and often (with more

effect) in some simple geometrical pattern amidst

the main walling of fl nt, greatly helps to give to

these fine old buildings that look of quiet dis-

tinction nearly always seen in the work of bygone

days' and so rarely in the buildings of to-day. The

art of the Norfolk building is appealing because it

DESIGNED AND DRAWN BY F. L. GRIGGS