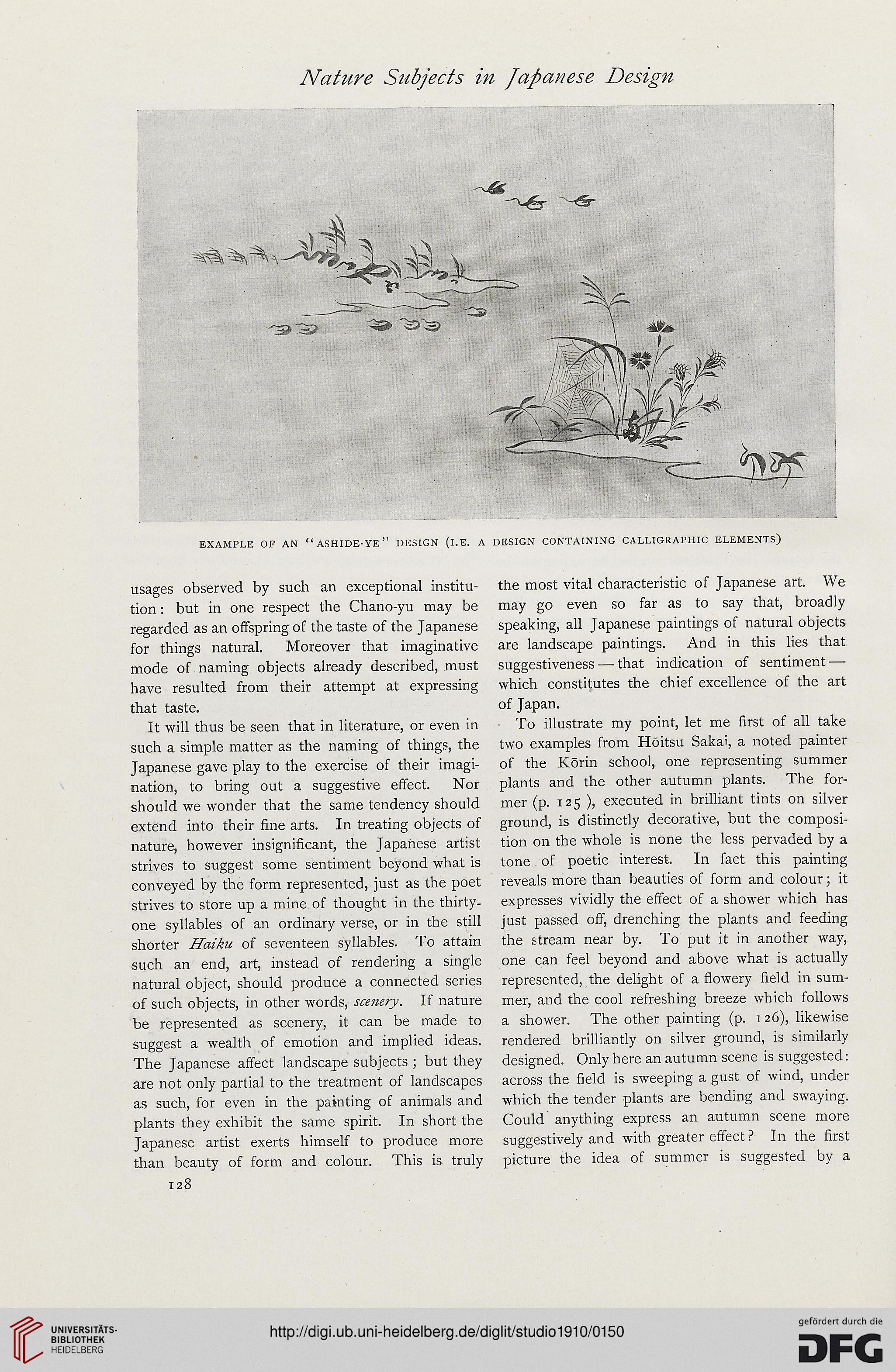

Nature Sttbjects in Japanese Design

usages observed by such an exceptional institu-

tion : but in one respect the Chano-yu may be

regarded as an offspring of the taste of the Japanese

for things natural. Moreover that imaginative

mode of naming objects already described, must

have resulted from their attempt at expressing

that taste.

It will thus be seen that in literature, or even in

such a simple matter as the naming of things, the

Japanese gave play to the exercise of their imagi-

nation, to bring out a suggestive effect. Nor

should we wonder that the same tendency should

extend into their fine arts. In treating objects of

nature, however insignificant, the Japanese artist

strives to suggest some sentiment beyond what is

conveyed by the form represented, just as the poet

strives to store up a mine of thought in the thirty-

one syllables of an ordinary verse, or in the still

shorter Haiku of seventeen syllables. To attain

such an end, art, instead of rendering a single

natural object, should produce a connected series

of such objects, in other words, scenery. If nature

be represented as scenery, it can be made to

suggest a wealth of emotion and implied ideas.

The Japanese affect landscape subjects; but they

are not only partial to the treatment of landscapes

as such, for even in the painting of animals and

plants they exhibit the same spirit. In short the

Japanese artist exerts himself to produce more

than beauty of form and colour. This is truly

128

the most vital characteristic of Japanese art. We

may go even so far as to say that, broadly

speaking, all Japanese paintings of natural objects

are landscape paintings. And in this lies that

suggestiveness — that indication of sentiment —

which constitutes the chief excellence of the art

of Japan.

To illustrate my point, let me first of all take

two examples from Hoitsu Sakai, a noted painter

of the Korin school, one representing summer

plants and the other autumn plants. The for-

mer (p. 125 ), executed in brilliant tints on silver

ground, is distinctly decorative, but the composi-

tion on the whole is none the less pervaded by a

tone of poetic interest. In fact this painting

reveals more than beauties of form and colour; it

expresses vividly the effect of a shower which has

just passed off, drenching the plants and feeding

the stream near by. To put it in another way,

one can feel beyond and above what is actually

represented, the delight of a flowery field in sum-

mer, and the cool refreshing breeze which follows

a shower. The other painting (p. 1 26), likewise

rendered brilliantly on silver ground, is similarly

designed. Only here an autumn scene is suggested:

across the field is sweeping a gust of wind, under

which the tender plants are bending and swaying.

Could anything express an autumn scene more

suggestively and with greater effect ? In the first

picture the idea of summer is suggested by a

usages observed by such an exceptional institu-

tion : but in one respect the Chano-yu may be

regarded as an offspring of the taste of the Japanese

for things natural. Moreover that imaginative

mode of naming objects already described, must

have resulted from their attempt at expressing

that taste.

It will thus be seen that in literature, or even in

such a simple matter as the naming of things, the

Japanese gave play to the exercise of their imagi-

nation, to bring out a suggestive effect. Nor

should we wonder that the same tendency should

extend into their fine arts. In treating objects of

nature, however insignificant, the Japanese artist

strives to suggest some sentiment beyond what is

conveyed by the form represented, just as the poet

strives to store up a mine of thought in the thirty-

one syllables of an ordinary verse, or in the still

shorter Haiku of seventeen syllables. To attain

such an end, art, instead of rendering a single

natural object, should produce a connected series

of such objects, in other words, scenery. If nature

be represented as scenery, it can be made to

suggest a wealth of emotion and implied ideas.

The Japanese affect landscape subjects; but they

are not only partial to the treatment of landscapes

as such, for even in the painting of animals and

plants they exhibit the same spirit. In short the

Japanese artist exerts himself to produce more

than beauty of form and colour. This is truly

128

the most vital characteristic of Japanese art. We

may go even so far as to say that, broadly

speaking, all Japanese paintings of natural objects

are landscape paintings. And in this lies that

suggestiveness — that indication of sentiment —

which constitutes the chief excellence of the art

of Japan.

To illustrate my point, let me first of all take

two examples from Hoitsu Sakai, a noted painter

of the Korin school, one representing summer

plants and the other autumn plants. The for-

mer (p. 125 ), executed in brilliant tints on silver

ground, is distinctly decorative, but the composi-

tion on the whole is none the less pervaded by a

tone of poetic interest. In fact this painting

reveals more than beauties of form and colour; it

expresses vividly the effect of a shower which has

just passed off, drenching the plants and feeding

the stream near by. To put it in another way,

one can feel beyond and above what is actually

represented, the delight of a flowery field in sum-

mer, and the cool refreshing breeze which follows

a shower. The other painting (p. 1 26), likewise

rendered brilliantly on silver ground, is similarly

designed. Only here an autumn scene is suggested:

across the field is sweeping a gust of wind, under

which the tender plants are bending and swaying.

Could anything express an autumn scene more

suggestively and with greater effect ? In the first

picture the idea of summer is suggested by a