Japanese Art and Artists of To-day.—III. Textiles and Embroidery

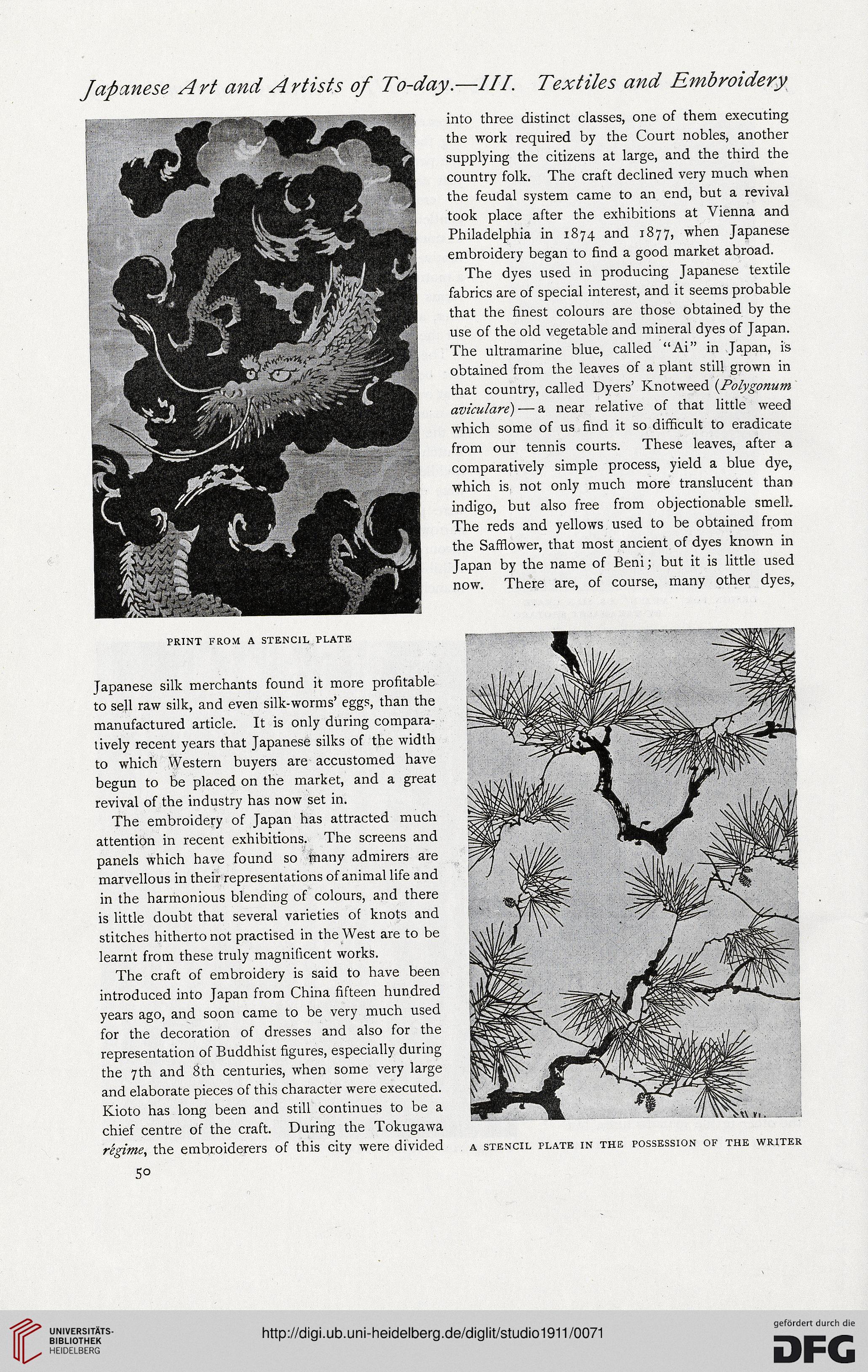

PRINT FROM A STENCIL PLATE

Japanese silk merchants found it more profitable

to sell raw silk, and even silk-worms’ eggs, than the

manufactured article. It is only during compara-

tively recent years that Japanese silks of the width

to which Western buyers are accustomed have

begun to be placed on the market, and a great

revival of the industry has now set in.

The embroidery of Japan has attracted much

attention in recent exhibitions. The screens and

panels which have found so many admirers are

marvellous in their representations of animal life and

in the harmonious blending of colours, and there

is little doubt that several varieties of knots and

stitches hitherto not practised in the West are to be

learnt from these truly magnificent works.

The craft of embroidery is said to have been

introduced into Japan from China fifteen hundred

years ago, and soon came to be very much used

for the decoration of dresses and also for the

representation of Buddhist figures, especially during

the 7th and $th centuries, when some very large

and elaborate pieces of this character were executed.

Kioto has long been and still continues to be a

chief centre of the craft. During the Tokugawa

regime, the embroiderers of this city were divided

5°

into three distinct classes, one of them executing

the work required by the Court nobles, another

supplying the citizens at large, and the third the

country folk. The craft declined very much when

the feudal system came to an end, but a revival

took place after the exhibitions at Vienna and

Philadelphia in 1874 and 1877, when Japanese

embroidery began to find a good market abroad.

The dyes used in producing Japanese textile

fabrics are of special interest, and it seems probable

that the finest colours are those obtained by the

use of the old vegetable and mineral dyes of Japan.

The ultramarine blue, called “Ai” in Japan, is

obtained from the leaves of a plant still grown in

that country, called Dyers’ Knotweed (Polygonum

aviculare) ■— a near relative of that little weed

which some of us find it so difficult to eradicate

from our tennis courts. These leaves, after a

comparatively simple process, yield a blue dye,

which is not only much more translucent than

indigo, but also free from objectionable smell.

The reds and yellows used to be obtained from

the Safflower, that most ancient of dyes known in

Japan by the name of Beni; but it is little used

now. There are, of course, many other dyes,

A STENCIL PLATE IN THE POSSESSION OF THE WRITER

PRINT FROM A STENCIL PLATE

Japanese silk merchants found it more profitable

to sell raw silk, and even silk-worms’ eggs, than the

manufactured article. It is only during compara-

tively recent years that Japanese silks of the width

to which Western buyers are accustomed have

begun to be placed on the market, and a great

revival of the industry has now set in.

The embroidery of Japan has attracted much

attention in recent exhibitions. The screens and

panels which have found so many admirers are

marvellous in their representations of animal life and

in the harmonious blending of colours, and there

is little doubt that several varieties of knots and

stitches hitherto not practised in the West are to be

learnt from these truly magnificent works.

The craft of embroidery is said to have been

introduced into Japan from China fifteen hundred

years ago, and soon came to be very much used

for the decoration of dresses and also for the

representation of Buddhist figures, especially during

the 7th and $th centuries, when some very large

and elaborate pieces of this character were executed.

Kioto has long been and still continues to be a

chief centre of the craft. During the Tokugawa

regime, the embroiderers of this city were divided

5°

into three distinct classes, one of them executing

the work required by the Court nobles, another

supplying the citizens at large, and the third the

country folk. The craft declined very much when

the feudal system came to an end, but a revival

took place after the exhibitions at Vienna and

Philadelphia in 1874 and 1877, when Japanese

embroidery began to find a good market abroad.

The dyes used in producing Japanese textile

fabrics are of special interest, and it seems probable

that the finest colours are those obtained by the

use of the old vegetable and mineral dyes of Japan.

The ultramarine blue, called “Ai” in Japan, is

obtained from the leaves of a plant still grown in

that country, called Dyers’ Knotweed (Polygonum

aviculare) ■— a near relative of that little weed

which some of us find it so difficult to eradicate

from our tennis courts. These leaves, after a

comparatively simple process, yield a blue dye,

which is not only much more translucent than

indigo, but also free from objectionable smell.

The reds and yellows used to be obtained from

the Safflower, that most ancient of dyes known in

Japan by the name of Beni; but it is little used

now. There are, of course, many other dyes,

A STENCIL PLATE IN THE POSSESSION OF THE WRITER