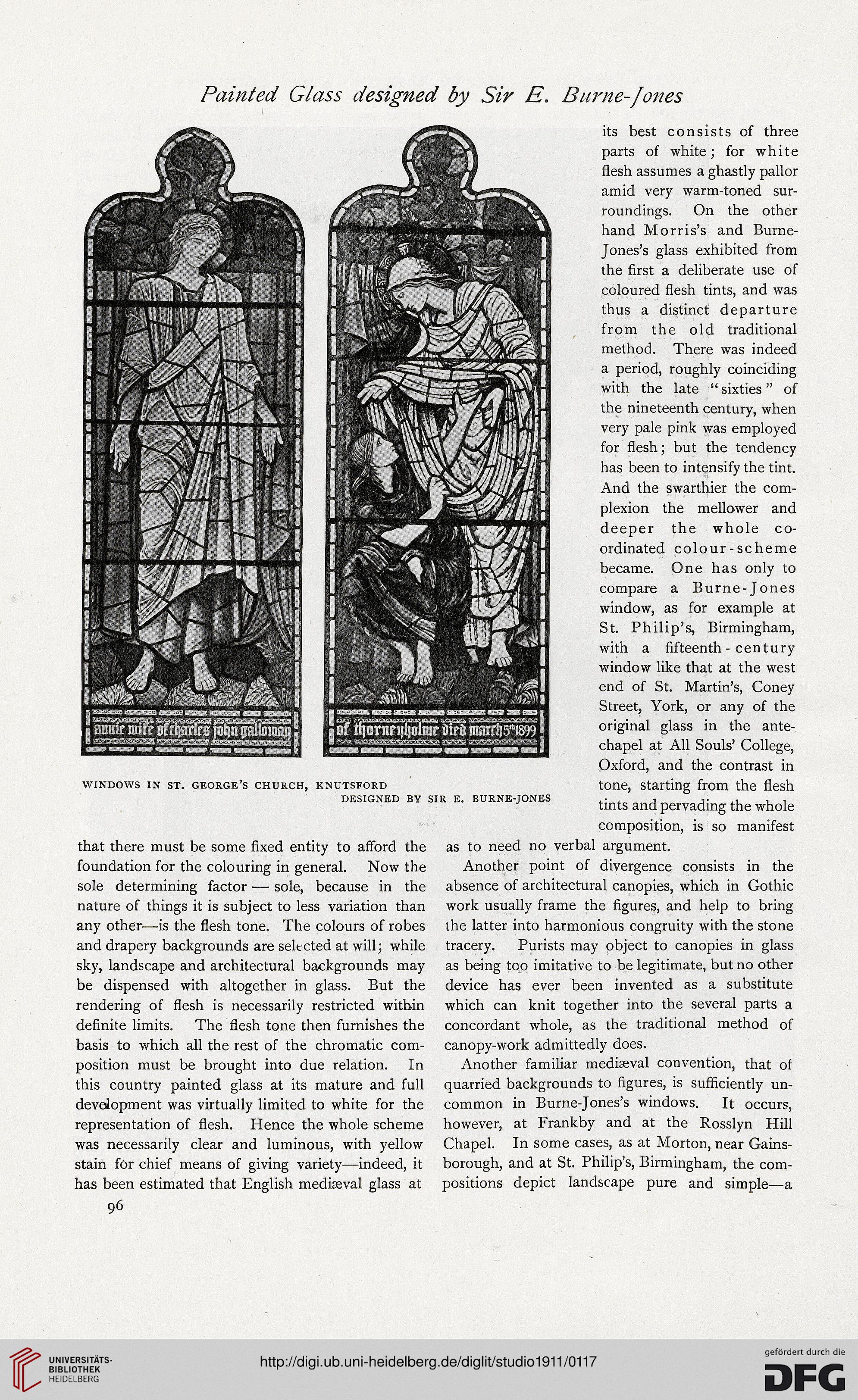

Painted Glass designed by Sir E. Burne-Jones

that there must be some fixed entity to afford the

foundation for the colouring in general. Now the

sole determining factor — sole, because in the

nature of things it is subject to less variation than

any other—is the flesh tone. The colours of robes

and drapery backgrounds are seltcted at will; while

sky, landscape and architectural backgrounds may

be dispensed with altogether in glass. But the

rendering of flesh is necessarily restricted within

definite limits. The flesh tone then furnishes the

basis to which all the rest of the chromatic com-

position must be brought into due relation. In

this country painted glass at its mature and full

development was virtually limited to white for the

representation of flesh. Hence the whole scheme

was necessarily clear and luminous, with yellow

stain for chief means of giving variety—indeed, it

has been estimated that English mediaeval glass at

96

its best consists of three

parts of white; for white

flesh assumes a ghastly pallor

amid very warm-toned sur-

roundings. On the other

hand Morris’s and Burne-

Jones’s glass exhibited from

the first a deliberate use of

coloured flesh tints, and was

thus a distinct departure

from the old traditional

method. There was indeed

a period, roughly coinciding

with the late “ sixties ” of

the nineteenth century, when

very pale pink was employed

for flesh; but the tendency

has been to intensify the tint.

And the swarthier the com-

plexion the mellower and

deeper the whole co-

ordinated colour-scheme

became. One has only to

compare a Burne-Jones

window, as for example at

St. Philip’s, Birmingham,

with a fifteenth - century

window like that at the west

end of St. Martin’s, Coney

Street, York, or any of the

original glass in the ante-

chapel at All Souls’ College,

Oxford, and the contrast in

tone, starting from the flesh

tints and pervading the whole

composition, is so manifest

as to need no verbal argument.

Another point of divergence consists in the

absence of architectural canopies, which in Gothic

work usually frame the figures, and help to bring

the latter into harmonious congruity with the stone

tracery. Purists may object to canopies in glass

as being too imitative to be legitimate, but no other

device has ever been invented as a substitute

which can knit together into the several parts a

concordant whole, as the traditional method of

canopy-work admittedly does.

Another familiar mediaeval convention, that ol

quarried backgrounds to figures, is sufficiently un-

common in Burne-Jones’s windows. It occurs,

however, at Frankby and at the Rosslyn Hill

Chapel. In some cases, as at Morton, near Gains-

borough, and at St. Philip’s, Birmingham, the com-

positions depict landscape pure and simple—a

that there must be some fixed entity to afford the

foundation for the colouring in general. Now the

sole determining factor — sole, because in the

nature of things it is subject to less variation than

any other—is the flesh tone. The colours of robes

and drapery backgrounds are seltcted at will; while

sky, landscape and architectural backgrounds may

be dispensed with altogether in glass. But the

rendering of flesh is necessarily restricted within

definite limits. The flesh tone then furnishes the

basis to which all the rest of the chromatic com-

position must be brought into due relation. In

this country painted glass at its mature and full

development was virtually limited to white for the

representation of flesh. Hence the whole scheme

was necessarily clear and luminous, with yellow

stain for chief means of giving variety—indeed, it

has been estimated that English mediaeval glass at

96

its best consists of three

parts of white; for white

flesh assumes a ghastly pallor

amid very warm-toned sur-

roundings. On the other

hand Morris’s and Burne-

Jones’s glass exhibited from

the first a deliberate use of

coloured flesh tints, and was

thus a distinct departure

from the old traditional

method. There was indeed

a period, roughly coinciding

with the late “ sixties ” of

the nineteenth century, when

very pale pink was employed

for flesh; but the tendency

has been to intensify the tint.

And the swarthier the com-

plexion the mellower and

deeper the whole co-

ordinated colour-scheme

became. One has only to

compare a Burne-Jones

window, as for example at

St. Philip’s, Birmingham,

with a fifteenth - century

window like that at the west

end of St. Martin’s, Coney

Street, York, or any of the

original glass in the ante-

chapel at All Souls’ College,

Oxford, and the contrast in

tone, starting from the flesh

tints and pervading the whole

composition, is so manifest

as to need no verbal argument.

Another point of divergence consists in the

absence of architectural canopies, which in Gothic

work usually frame the figures, and help to bring

the latter into harmonious congruity with the stone

tracery. Purists may object to canopies in glass

as being too imitative to be legitimate, but no other

device has ever been invented as a substitute

which can knit together into the several parts a

concordant whole, as the traditional method of

canopy-work admittedly does.

Another familiar mediaeval convention, that ol

quarried backgrounds to figures, is sufficiently un-

common in Burne-Jones’s windows. It occurs,

however, at Frankby and at the Rosslyn Hill

Chapel. In some cases, as at Morton, near Gains-

borough, and at St. Philip’s, Birmingham, the com-

positions depict landscape pure and simple—a