Edward Stott, A.R.A.

the success of the last two pictures heartened the

painter into seeking some permanent resting-

ground on native soil. In his wanderings he

happened into Sussex, and seeing Amberley has

remained there for over a quarter of a century.

Primrose Day was the first canvas tackled in

the new environment, and was exhibited in

Piccadilly in 1885. The year 1885, then, may

be said to have been the decisive turning-point in

Mr. Stott’s life. So sensitive an artist needed a

restful atmosphere, and in the pure Saxon popula-

tion of rustic Sussex he found exactly what he

craved for.

To enumerate the output of Mr. Edward Stott is

not possible within the slender limits of one article.

Yet the picture called The Ferry, exhibited in 1887,

and purchased by the Oldham Corporation, the

two canvases, Gleaners and In an Orchard, seen at

the New Gallery in 1892, Milking Time—Early

Morning, shown at the New English Art Club,

1894, The White Cow, and Noonday—Boys Bathing,'

all belong to the artist’s

best period. But space

presses. Only roughly and

in a cursory way can be

mentioned Bathers, exhi-

bited at the Royal Academy

in 1890; Home by the Ferry,

Snowstorm, and Nature's

Mirror, seen on the same

walls in 189T; Red Roses

(1892), Black Horse and

Ploughboy (1896), The Little

Violinist (1888), The Har-

vester's Return (1899), The

River Bank (1901), Peaceful

Rest and Youth and Age

(1902), The Gleaners and

Echo (t903), The Old Barge

(1904), The Shepherd {1905),

Lambing Time (1906), The

Reaper and the Maid and

Belated (1907), The Kiss

(reproduced in these pages),

The Flamingoes, and The

Cloisonnt Sky (r9o8), The

Flight (1909), The Good

Samaritan and There was

no Room in the Inn (1910),

Her thoughts were her

Children, and—perhaps one

of the most tender and trans-

lucent of all his canvases—

Hagar and Ishmael.

The mention of The Good Samaritan (another

picture already seen in the pages of the Studio)

reminds me of the latest phase of Mr. Stott’s art.

I mean his religious art. Was it not M. de

Goncourt who once spoke of a virgin’s forehead

bombi dlinnocence ? The chief difficulty of the

modern artist is to find models expressing the

detachment, the subservience, the acceptance that

we find writ large on the face of every saint and

angel portrayed by the early masters. Now is it

that the innocence or the artist has departed in

the tortured “ prickly ” age in which we live ? The

genius of Mr. Edward Stott gives us the answer.

For though he treats his religious subjects, for the

most part, from their simple human side, he sees

with the inner eye as well as the outward. And

in this sense again he brings us harmony, the

harmony with which he would envelop and en-

compass the world. M. H. D.

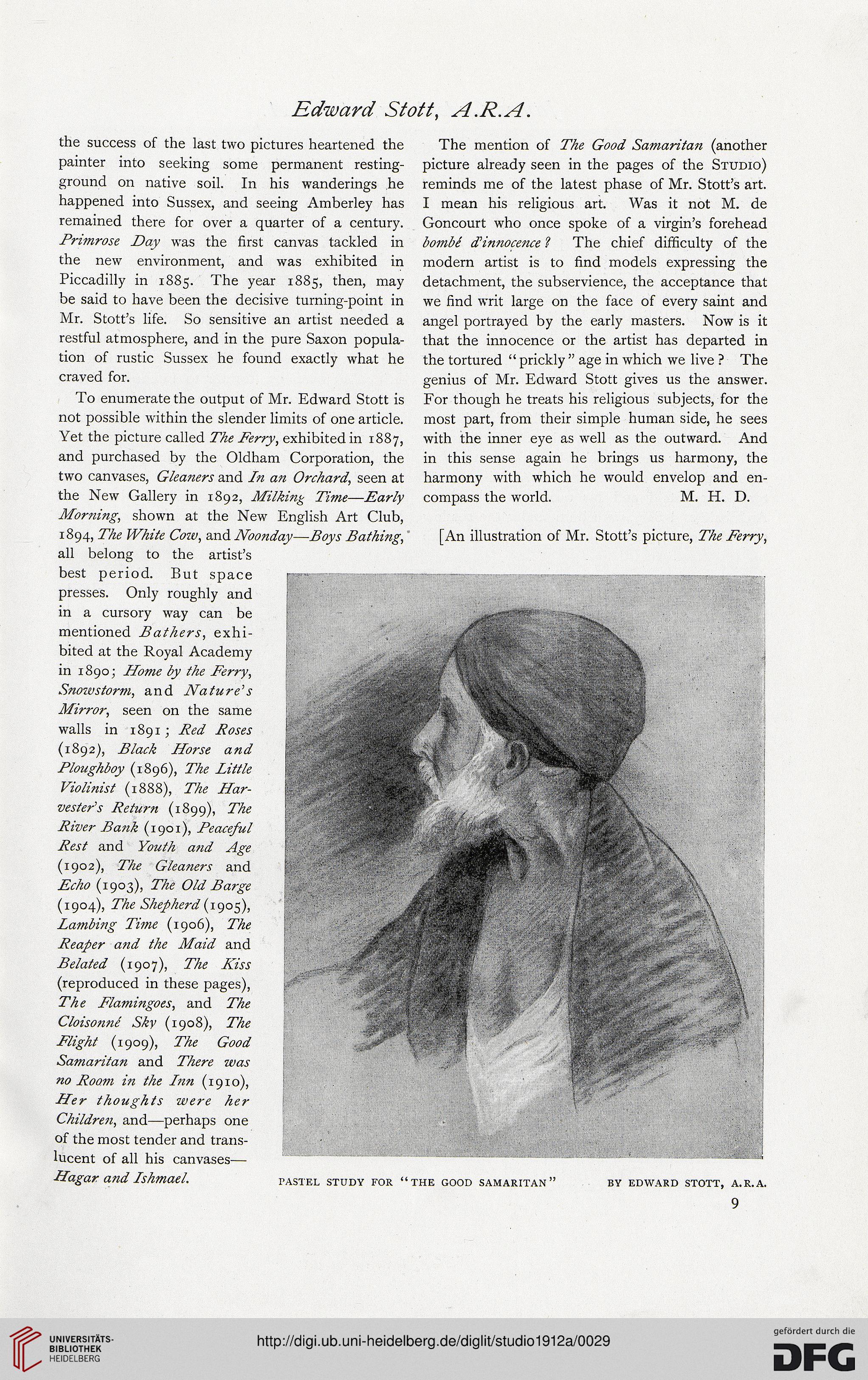

[An illustration of Mr. Stott’s picture, The Ferry,

the success of the last two pictures heartened the

painter into seeking some permanent resting-

ground on native soil. In his wanderings he

happened into Sussex, and seeing Amberley has

remained there for over a quarter of a century.

Primrose Day was the first canvas tackled in

the new environment, and was exhibited in

Piccadilly in 1885. The year 1885, then, may

be said to have been the decisive turning-point in

Mr. Stott’s life. So sensitive an artist needed a

restful atmosphere, and in the pure Saxon popula-

tion of rustic Sussex he found exactly what he

craved for.

To enumerate the output of Mr. Edward Stott is

not possible within the slender limits of one article.

Yet the picture called The Ferry, exhibited in 1887,

and purchased by the Oldham Corporation, the

two canvases, Gleaners and In an Orchard, seen at

the New Gallery in 1892, Milking Time—Early

Morning, shown at the New English Art Club,

1894, The White Cow, and Noonday—Boys Bathing,'

all belong to the artist’s

best period. But space

presses. Only roughly and

in a cursory way can be

mentioned Bathers, exhi-

bited at the Royal Academy

in 1890; Home by the Ferry,

Snowstorm, and Nature's

Mirror, seen on the same

walls in 189T; Red Roses

(1892), Black Horse and

Ploughboy (1896), The Little

Violinist (1888), The Har-

vester's Return (1899), The

River Bank (1901), Peaceful

Rest and Youth and Age

(1902), The Gleaners and

Echo (t903), The Old Barge

(1904), The Shepherd {1905),

Lambing Time (1906), The

Reaper and the Maid and

Belated (1907), The Kiss

(reproduced in these pages),

The Flamingoes, and The

Cloisonnt Sky (r9o8), The

Flight (1909), The Good

Samaritan and There was

no Room in the Inn (1910),

Her thoughts were her

Children, and—perhaps one

of the most tender and trans-

lucent of all his canvases—

Hagar and Ishmael.

The mention of The Good Samaritan (another

picture already seen in the pages of the Studio)

reminds me of the latest phase of Mr. Stott’s art.

I mean his religious art. Was it not M. de

Goncourt who once spoke of a virgin’s forehead

bombi dlinnocence ? The chief difficulty of the

modern artist is to find models expressing the

detachment, the subservience, the acceptance that

we find writ large on the face of every saint and

angel portrayed by the early masters. Now is it

that the innocence or the artist has departed in

the tortured “ prickly ” age in which we live ? The

genius of Mr. Edward Stott gives us the answer.

For though he treats his religious subjects, for the

most part, from their simple human side, he sees

with the inner eye as well as the outward. And

in this sense again he brings us harmony, the

harmony with which he would envelop and en-

compass the world. M. H. D.

[An illustration of Mr. Stott’s picture, The Ferry,