Sir George Reid's Portraits

applied to himself. The same point of view is

evident in The Rev. Dr. Mitchell, in Dr. Walter

Smith, and Thomas Graham Murray. Indeed,

in his presentation of Church dignitaries he paints

them as members of a Church Militant. Behind

his Scottish divines stands the full defiance of the

Solemn League and Covenant and the Thirty-nine

Articles. When you look into their faces you

think of Drumclog and Airds Moss, of John Knox

and Andrew Melville.

Sir George Reid’s Scotsmen could never be any-

thing else than men of the Don and the Dee, the

Clyde and the Forth. They carry their country on

their shoulders, in the conscious independence of

the eyes, in the ruggedness of the cheek. Sir

James Guthrie’s men of the north are not em-

phatically Scottish. Always full of character, they

do not bear their sign-manual of nationality so

characteristically as do those of his predecessor.

If Guthrie had painted Thomas Carlyle, he would

have seen him with the eyes of Whistler, upon which

vision he would have superimposed his own insight

into the spiritual significance of his sitter. If Sir

George Reid had painted the Chelsea sage, he

would have presented him as the Thunderer full

armed against the battalions of sham and humbug,

and the Lowland Scot in him would have called to

you with the murmur of the Tweed and the war-cry

of the Border riever.

The decorative principles as practised by Whistler

and the members of the Glasgow and other modern

schools are not to be sought for in a portrait by

Reid. He does not use his sitter merely as the

centre for a scheme of colour. At his worst—which

is never bad—the background is a negligible

quantity ; at his best—which is superlatively fine—

it does not share with any sense of equality in the

importance of the general design. This design is

never complex. Its very simplicity has led some

to belittle the artistic achievement. But we are

convinced that the simplicity of the

design is intentional as directing the eye

to the character of the person presented

more than to the decorative quality of

the canvas. The critics of Sir George

Reid who find the first virtue in com-

plete tonality hasten to compare one of

his portraits with those of men who are

enthusiasts for tonal decoration in por-

traiture. Whether such a comparison is

relevant is another matter. It all de-

pends on the object aimed at by the

painter. Sir George Reid might argue

that what is called the decorative school

is apt to belittle the sitter at the expense

of the general scheme. This criticism

might apply to such a master as Mr.

William Nicholson, not by any means

always, but occasionally, and it applies

here and there to his gifted colleague,

Mr. Orpen. If objection can be taken

to Sir George Reid’s direct and forceful

method, it is that the portrait is apt to

give the impression of being quickly laid

down on the canvas, and not, as it were,

growing slowly out of the paint into

superb life, as is the case with the best

examples of Sir James Guthrie and Mr.

Walton. This was more evident in

some early portraits, but in his later

successes, such as the Tom Morris and

The Earl of Halsbury, the painter seems

to have had a fuller consciousness of the

need of a more uniform pictorial method.

173

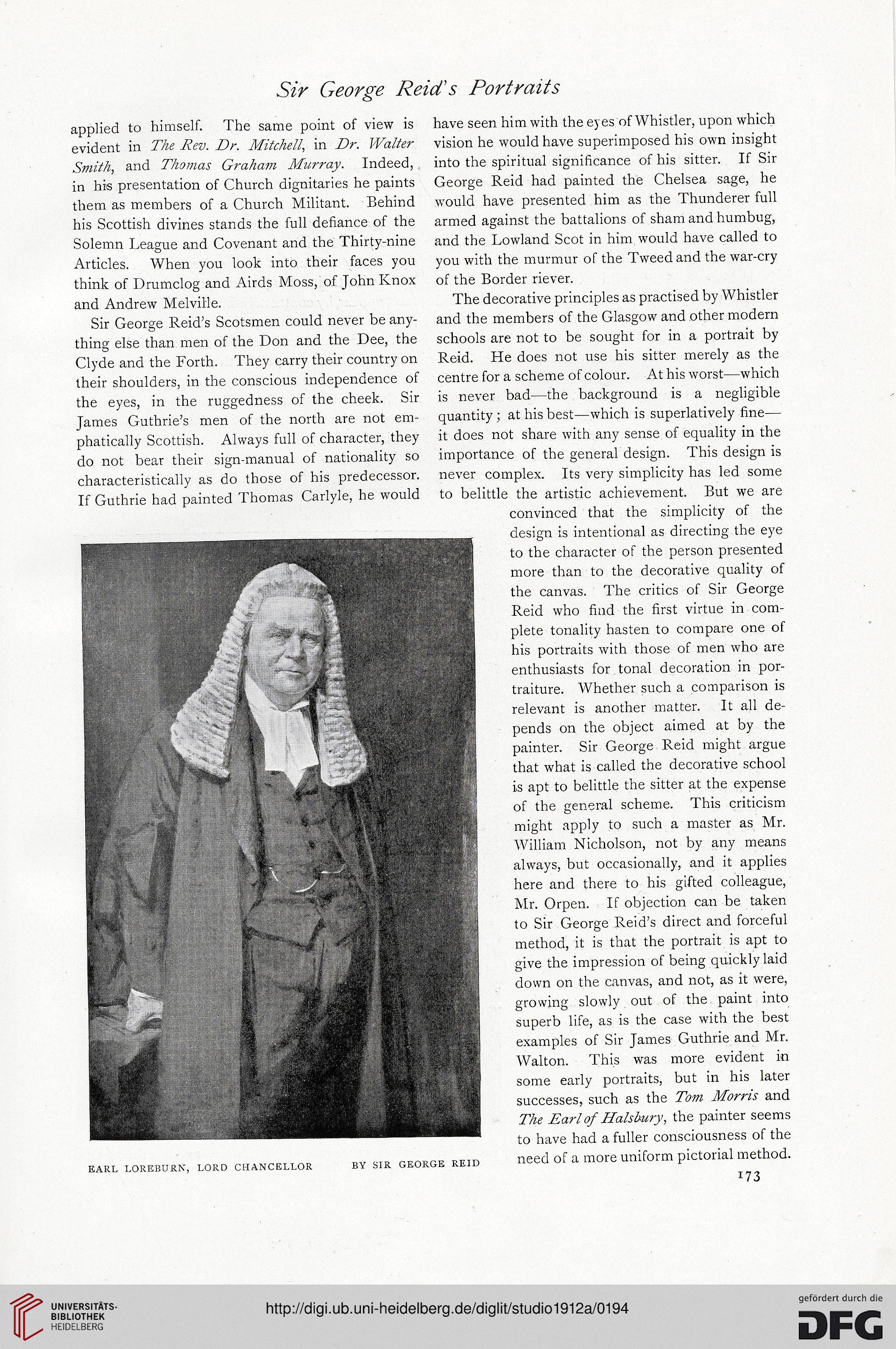

EARL LOREBURN, LORD CHANCELLOR BY SIR GEORGE REID

applied to himself. The same point of view is

evident in The Rev. Dr. Mitchell, in Dr. Walter

Smith, and Thomas Graham Murray. Indeed,

in his presentation of Church dignitaries he paints

them as members of a Church Militant. Behind

his Scottish divines stands the full defiance of the

Solemn League and Covenant and the Thirty-nine

Articles. When you look into their faces you

think of Drumclog and Airds Moss, of John Knox

and Andrew Melville.

Sir George Reid’s Scotsmen could never be any-

thing else than men of the Don and the Dee, the

Clyde and the Forth. They carry their country on

their shoulders, in the conscious independence of

the eyes, in the ruggedness of the cheek. Sir

James Guthrie’s men of the north are not em-

phatically Scottish. Always full of character, they

do not bear their sign-manual of nationality so

characteristically as do those of his predecessor.

If Guthrie had painted Thomas Carlyle, he would

have seen him with the eyes of Whistler, upon which

vision he would have superimposed his own insight

into the spiritual significance of his sitter. If Sir

George Reid had painted the Chelsea sage, he

would have presented him as the Thunderer full

armed against the battalions of sham and humbug,

and the Lowland Scot in him would have called to

you with the murmur of the Tweed and the war-cry

of the Border riever.

The decorative principles as practised by Whistler

and the members of the Glasgow and other modern

schools are not to be sought for in a portrait by

Reid. He does not use his sitter merely as the

centre for a scheme of colour. At his worst—which

is never bad—the background is a negligible

quantity ; at his best—which is superlatively fine—

it does not share with any sense of equality in the

importance of the general design. This design is

never complex. Its very simplicity has led some

to belittle the artistic achievement. But we are

convinced that the simplicity of the

design is intentional as directing the eye

to the character of the person presented

more than to the decorative quality of

the canvas. The critics of Sir George

Reid who find the first virtue in com-

plete tonality hasten to compare one of

his portraits with those of men who are

enthusiasts for tonal decoration in por-

traiture. Whether such a comparison is

relevant is another matter. It all de-

pends on the object aimed at by the

painter. Sir George Reid might argue

that what is called the decorative school

is apt to belittle the sitter at the expense

of the general scheme. This criticism

might apply to such a master as Mr.

William Nicholson, not by any means

always, but occasionally, and it applies

here and there to his gifted colleague,

Mr. Orpen. If objection can be taken

to Sir George Reid’s direct and forceful

method, it is that the portrait is apt to

give the impression of being quickly laid

down on the canvas, and not, as it were,

growing slowly out of the paint into

superb life, as is the case with the best

examples of Sir James Guthrie and Mr.

Walton. This was more evident in

some early portraits, but in his later

successes, such as the Tom Morris and

The Earl of Halsbury, the painter seems

to have had a fuller consciousness of the

need of a more uniform pictorial method.

173

EARL LOREBURN, LORD CHANCELLOR BY SIR GEORGE REID