D. Y. Cameron s Paintings

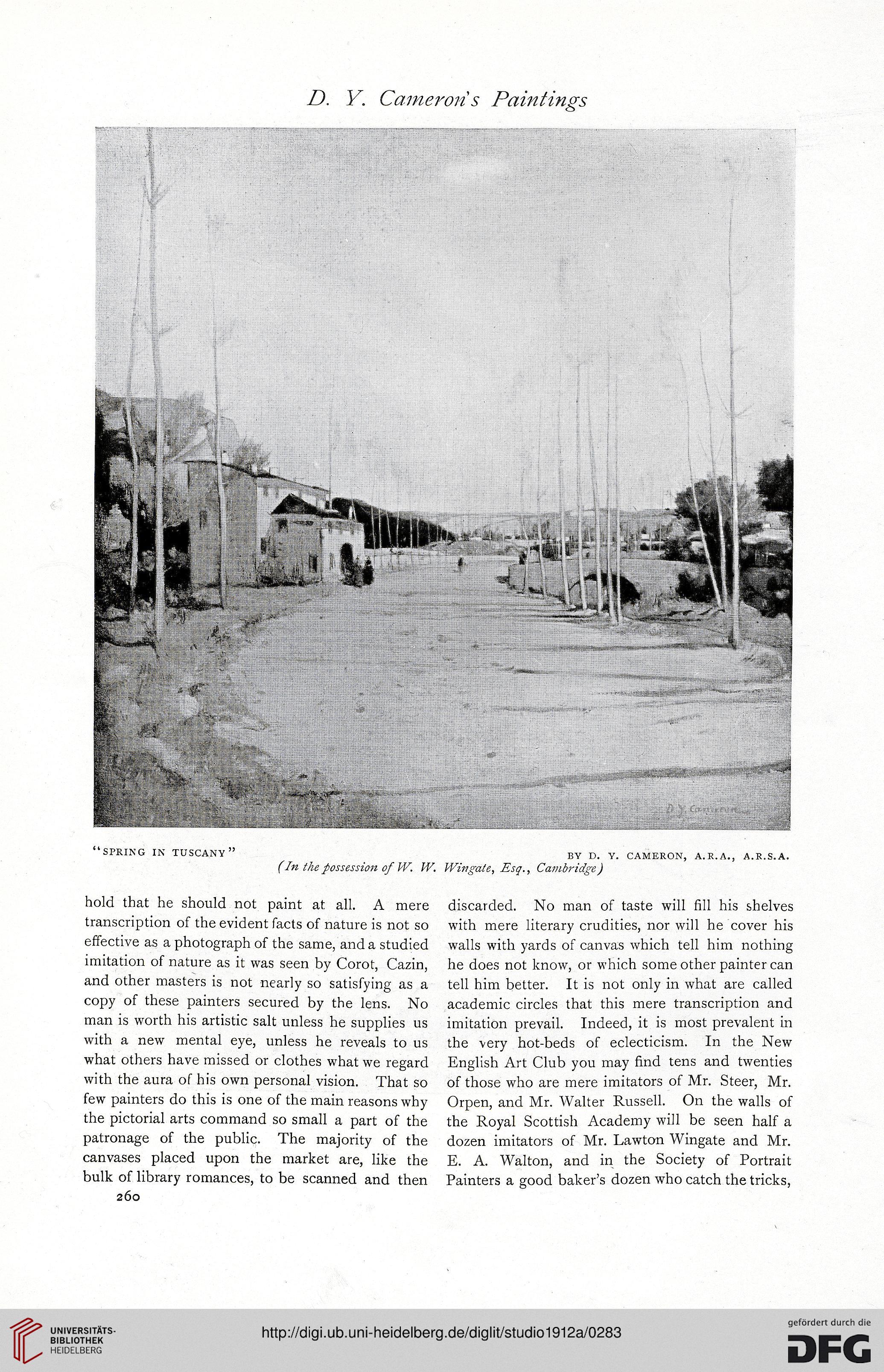

“SPRING IN TUSCANY” BY D. V. CAMERON, A.R.A., A.R.S.A.

(In the possession of W. W. Wingate, Esq., Cambridge)

hold that he should not paint at all. A mere

transcription of the evident facts of nature is not so

effective as a photograph of the same, and a studied

imitation of nature as it was seen by Corot, Cazin,

and other masters is not nearly so satisfying as a

copy of these painters secured by the lens. No

man is worth his artistic salt unless he supplies us

with a new mental eye, unless he reveals to us

what others have missed or clothes what we regard

with the aura of his own personal vision. That so

few painters do this is one of the main reasons why

the pictorial arts command so small a part of the

patronage of the public. The majority of the

canvases placed upon the market are, like the

bulk of library romances, to be scanned and then

260

discarded. No man of taste will fill his shelves

with mere literary crudities, nor will he cover his

walls with yards of canvas which tell him nothing

he does not know, or which some other painter can

tell him better. It is not only in what are called

academic circles that this mere transcription and

imitation prevail. Indeed, it is most prevalent in

the very hot-beds of eclecticism. In the New

English Art Club you may find tens and twenties

of those who are mere imitators of Mr. Steer, Mr.

Orpen, and Mr. Walter Russell. On the walls of

the Royal Scottish Academy will be seen half a

dozen imitators of Mr. Lawton Wingate and Mr.

E. A. Walton, and in the Society of Portrait

Painters a good baker’s dozen who catch the tricks,

“SPRING IN TUSCANY” BY D. V. CAMERON, A.R.A., A.R.S.A.

(In the possession of W. W. Wingate, Esq., Cambridge)

hold that he should not paint at all. A mere

transcription of the evident facts of nature is not so

effective as a photograph of the same, and a studied

imitation of nature as it was seen by Corot, Cazin,

and other masters is not nearly so satisfying as a

copy of these painters secured by the lens. No

man is worth his artistic salt unless he supplies us

with a new mental eye, unless he reveals to us

what others have missed or clothes what we regard

with the aura of his own personal vision. That so

few painters do this is one of the main reasons why

the pictorial arts command so small a part of the

patronage of the public. The majority of the

canvases placed upon the market are, like the

bulk of library romances, to be scanned and then

260

discarded. No man of taste will fill his shelves

with mere literary crudities, nor will he cover his

walls with yards of canvas which tell him nothing

he does not know, or which some other painter can

tell him better. It is not only in what are called

academic circles that this mere transcription and

imitation prevail. Indeed, it is most prevalent in

the very hot-beds of eclecticism. In the New

English Art Club you may find tens and twenties

of those who are mere imitators of Mr. Steer, Mr.

Orpen, and Mr. Walter Russell. On the walls of

the Royal Scottish Academy will be seen half a

dozen imitators of Mr. Lawton Wingate and Mr.

E. A. Walton, and in the Society of Portrait

Painters a good baker’s dozen who catch the tricks,