IV. G. von Glehn

his portraits in keeping an element of charm in the

canvas. This was a secret of seventeenth- and

eighteenth-century art; and it is one at least of the

elements that induce an ordinary person to regard

a portrait as a work of art. There is much to be

said for the ordinary point of view in this matter

too. It has remained for our own age to produce

an infinite quantity of portraits possessing no single

element necessary to a picture—the sort of portrait

that rests its whole claim upon its likeness to a

sitter who has probably never been seen or heard

of by us. The likeness is said to be there if the

expression is caught, though in “ flesh ” colour

that resembles nothing human. Less than a

century ago even quite unknown painters, whose

work is to be found in country houses, understood

that portrait-painting was a branch of picture-

making. Mr. von Glehn to-day does not fail his

sitters in this respect. They go to him as an artist,

and perhaps after their experiences of portrait-

painters in general they are surprised to find he

is one.

Part of Mr. von Glehn’s success in the province

of portraiture is no doubt due to the fact that he is

so successful with the figure. In pictures of land-

scape surroundings he is accustomed to introduce

groups in spontaneous action. When then it is

a question of a portrait, more easily than many

artists he can capture a spontaneous pose. That

his technique is particularly suitable for securing

the elusive and indefinite traits upon which facial

expression depends has been proved by the success

of the school to which his method of painting a

portrait obviously belongs.

In his out-of-doors figure-pictures the artist has

used two kinds of subjects, those in which women

in fairy-white dresses enter into the life of a summer

day; and those more formal, improbable decora-

tions with a background of garden architecture.

Except for the nude in the latter, we have practi-

cally the Watteau subject up to date, with the

less romantic modern outlook, and the distinction

between what is matter-of-fact and what is matter

of imagination, which all but modern art has striven

so sincerely to obscure. To give the illusion that

things too beautiful to be real were real was the

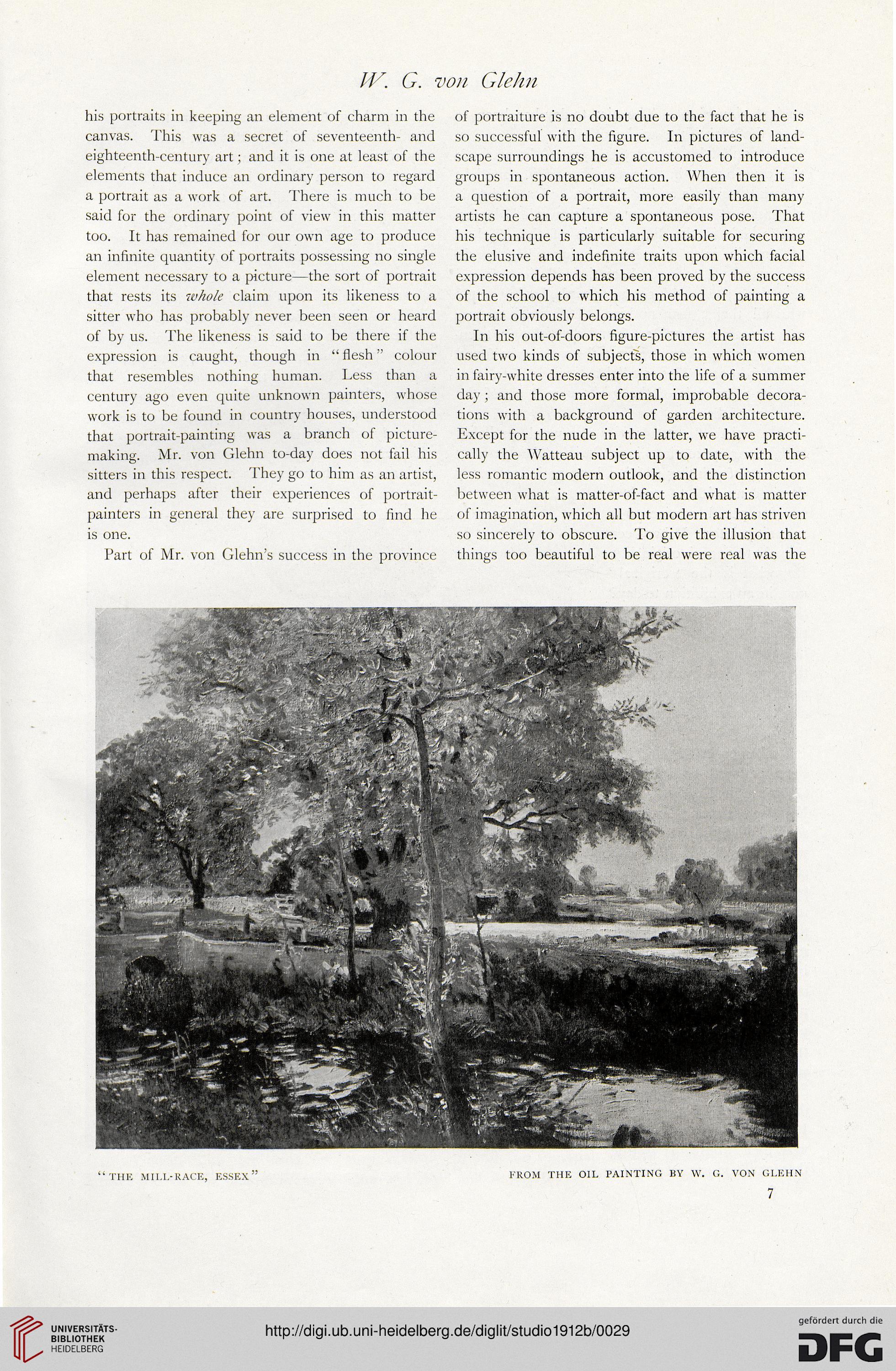

“THE MILL-RACE, ESSEX

his portraits in keeping an element of charm in the

canvas. This was a secret of seventeenth- and

eighteenth-century art; and it is one at least of the

elements that induce an ordinary person to regard

a portrait as a work of art. There is much to be

said for the ordinary point of view in this matter

too. It has remained for our own age to produce

an infinite quantity of portraits possessing no single

element necessary to a picture—the sort of portrait

that rests its whole claim upon its likeness to a

sitter who has probably never been seen or heard

of by us. The likeness is said to be there if the

expression is caught, though in “ flesh ” colour

that resembles nothing human. Less than a

century ago even quite unknown painters, whose

work is to be found in country houses, understood

that portrait-painting was a branch of picture-

making. Mr. von Glehn to-day does not fail his

sitters in this respect. They go to him as an artist,

and perhaps after their experiences of portrait-

painters in general they are surprised to find he

is one.

Part of Mr. von Glehn’s success in the province

of portraiture is no doubt due to the fact that he is

so successful with the figure. In pictures of land-

scape surroundings he is accustomed to introduce

groups in spontaneous action. When then it is

a question of a portrait, more easily than many

artists he can capture a spontaneous pose. That

his technique is particularly suitable for securing

the elusive and indefinite traits upon which facial

expression depends has been proved by the success

of the school to which his method of painting a

portrait obviously belongs.

In his out-of-doors figure-pictures the artist has

used two kinds of subjects, those in which women

in fairy-white dresses enter into the life of a summer

day; and those more formal, improbable decora-

tions with a background of garden architecture.

Except for the nude in the latter, we have practi-

cally the Watteau subject up to date, with the

less romantic modern outlook, and the distinction

between what is matter-of-fact and what is matter

of imagination, which all but modern art has striven

so sincerely to obscure. To give the illusion that

things too beautiful to be real were real was the

“THE MILL-RACE, ESSEX