Edward Lanteri

as an expression of his own remarkable personality ;

he holds that “ sculpture is three-quarters scientific

knowledge,” and he has established his system

on a firm scientific basis. In speaking of his own

student days at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he said

there was no teaching in the real sense of the word.

“ I was told only that ‘ this was right and that was

wrong, that is too long or too short,’ and no more

than that. The best teacher of that time, to whom

I owe so much, was M. Lecocq de Boisbaudran.

His excellent lessons are still present in my

mind. . . .

“ Taking the question of drapery, I used to copy

it diligently, piece by piece, but I never understoo d

or had pointed out to me any rule which would

have simplified it. When I came to teach others,

BY EDWARD I.AN’TERI

I thought a great deal of how to overcome some of

the many difficulties to help my pupils, and I found

that, by applying certain laws of nature to the

obstacles, the difficulties vanished at once. The

law of radiation, for instance, solved the problem of

drapery, and the same law applies to the whole

construction of the human figure.”

The hurry and superficiality of the education of

the modern art student, Prof. Lanteri protests

against greatly. “ In the past there was less haste,

and study was more profound. Nowadays it is

rendered easy—a grave peril for the mind, which

becomes superficial and fickle. Study may often

be a kind of lure, by which students allow them-

selves to be caught; they grasp at its semblance,

and it only serves them to disguise ignorance under

an audacious cleverness.” For slipshod methods

he has no toleration. He holds that the period

of training should be prolonged until the student

has passed beyond the age of uncertainty and has

acquired strength of character and clearness of

aim.

On the subject of composition he says : “ For a

master to impose on his pupil his own conception

of a subject, is entirely contrary to the rules of

artistic teaching. In such case, the hand of the

student becomes merely the instrument of the

teacher’s brain, and he never acquires the needful

strength of conviction to produce a work of in-

dividual quality—the only result being that the

student loses all interest in pursuing and perfecting

his own conception. And yet this is just what

the master ought to assist him in, by speaking to

him of the masterpieces of old, and by using

all possible means that will help him to give

expression to his own thoughts and sentiments.”

Also : “ A true teacher must exclude the systematic

spirit from his judgment. Far from seeming to

keep exclusively to one conception of art only, he

must understand all those conceptions which have

been produced before, and must be able to receive

from his pupils all the new modes of expression

which can still be brought forth. Above all he

must never put his own example forward; he

should be absolutely impersonal.” And again:

“ In order to develop the artistic intelligence you

must work from nature with the greatest sincerity;

copy flowers or leaves, or whatsoever it may be,

with the most scrupulous analysis of their character

and forms, for Nature only reveals herself to him

who studies her with a loving eye. In this way

the student will find the essence of the spirit of

composition, for there is nothing more harmonious,

nothing more symmetrical than a flower, a leaf,

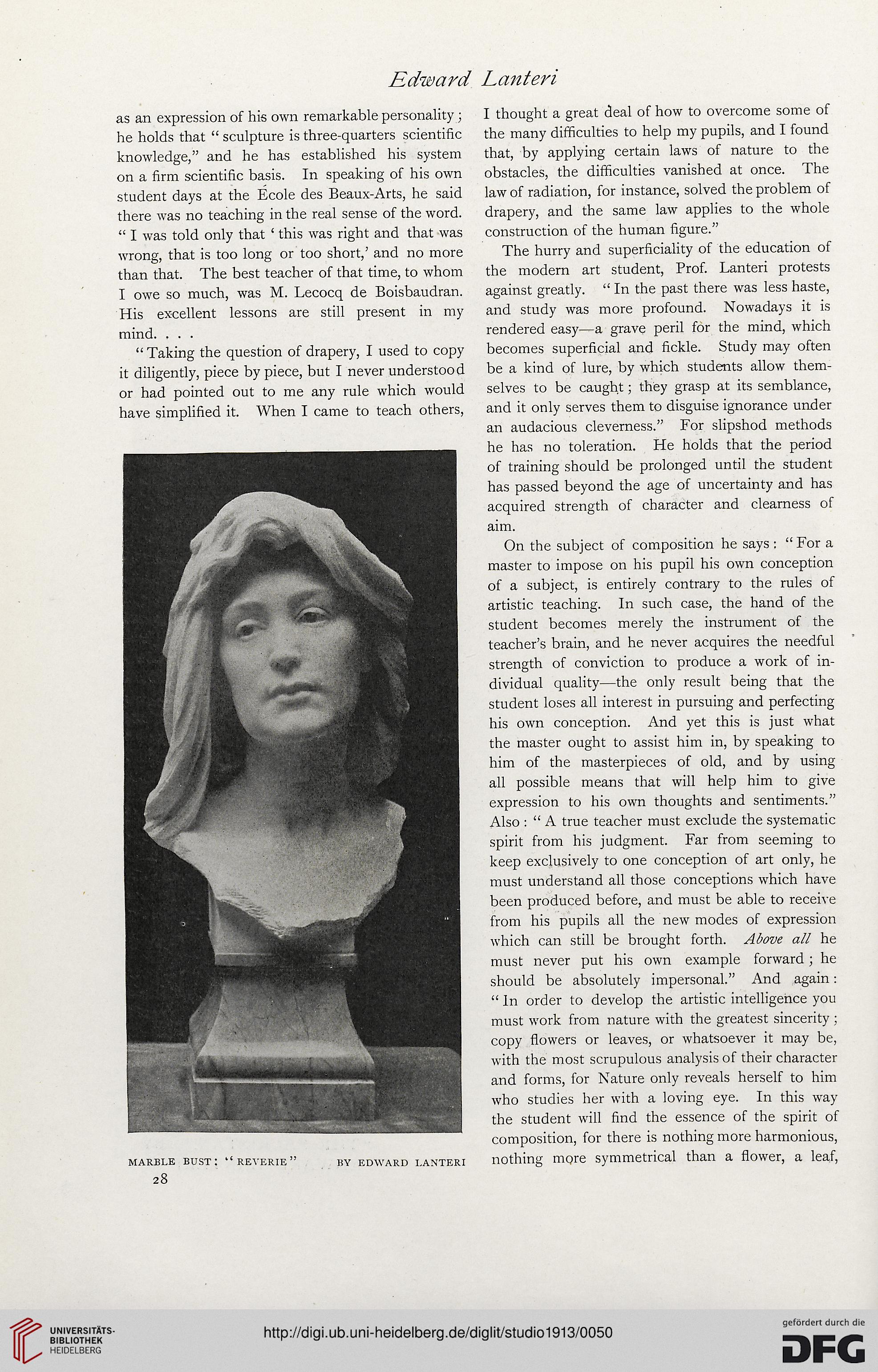

MARBLE bust: “REVERIE

as an expression of his own remarkable personality ;

he holds that “ sculpture is three-quarters scientific

knowledge,” and he has established his system

on a firm scientific basis. In speaking of his own

student days at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he said

there was no teaching in the real sense of the word.

“ I was told only that ‘ this was right and that was

wrong, that is too long or too short,’ and no more

than that. The best teacher of that time, to whom

I owe so much, was M. Lecocq de Boisbaudran.

His excellent lessons are still present in my

mind. . . .

“ Taking the question of drapery, I used to copy

it diligently, piece by piece, but I never understoo d

or had pointed out to me any rule which would

have simplified it. When I came to teach others,

BY EDWARD I.AN’TERI

I thought a great deal of how to overcome some of

the many difficulties to help my pupils, and I found

that, by applying certain laws of nature to the

obstacles, the difficulties vanished at once. The

law of radiation, for instance, solved the problem of

drapery, and the same law applies to the whole

construction of the human figure.”

The hurry and superficiality of the education of

the modern art student, Prof. Lanteri protests

against greatly. “ In the past there was less haste,

and study was more profound. Nowadays it is

rendered easy—a grave peril for the mind, which

becomes superficial and fickle. Study may often

be a kind of lure, by which students allow them-

selves to be caught; they grasp at its semblance,

and it only serves them to disguise ignorance under

an audacious cleverness.” For slipshod methods

he has no toleration. He holds that the period

of training should be prolonged until the student

has passed beyond the age of uncertainty and has

acquired strength of character and clearness of

aim.

On the subject of composition he says : “ For a

master to impose on his pupil his own conception

of a subject, is entirely contrary to the rules of

artistic teaching. In such case, the hand of the

student becomes merely the instrument of the

teacher’s brain, and he never acquires the needful

strength of conviction to produce a work of in-

dividual quality—the only result being that the

student loses all interest in pursuing and perfecting

his own conception. And yet this is just what

the master ought to assist him in, by speaking to

him of the masterpieces of old, and by using

all possible means that will help him to give

expression to his own thoughts and sentiments.”

Also : “ A true teacher must exclude the systematic

spirit from his judgment. Far from seeming to

keep exclusively to one conception of art only, he

must understand all those conceptions which have

been produced before, and must be able to receive

from his pupils all the new modes of expression

which can still be brought forth. Above all he

must never put his own example forward; he

should be absolutely impersonal.” And again:

“ In order to develop the artistic intelligence you

must work from nature with the greatest sincerity;

copy flowers or leaves, or whatsoever it may be,

with the most scrupulous analysis of their character

and forms, for Nature only reveals herself to him

who studies her with a loving eye. In this way

the student will find the essence of the spirit of

composition, for there is nothing more harmonious,

nothing more symmetrical than a flower, a leaf,

MARBLE bust: “REVERIE