Harold and Laura Knight

really a logical sequence to the influences already

affecting them. This hollow land, banked and

buttressed against the grey tumbling waters of the

North Sea, has always been a land of artists and,

strangely enough, considering its artificial nature, a

land of landscape painters. Great clouds sweep

up from the ocean and are mirrored in still canals

bordered by stately rows of trees. The cities, too,

built in old days by wealthy burghers and prosperous

merchants from Batavia and the East Indies,

duplicate themselves in bright, quivering reflections

on waterways populous with slow-moving barges,

radiant with the colour of a paint-loving people.

Here in the land of Israels, of the brothers Maris,

of Mauve, of countless names enshrined in the

history of art, the Knights set themselves to study

atmosphere and composition. The most obvious

effect of the Dutch influence was in causing them

to rely on a very reticent scheme of colour, discreet

greys, and rich mysterious shadows. A certain

lowness of tone both in colour and also in sentiment

marks this period. Harold Knight painted a large

picture called Grace which George Clausen, R.A.,

bought for the Cape in 1907 ; this was reproduced

in The Studio last year.

The next move was to Newlyn and another page

is turned. The Newlyn group has always had the

reputation of seeing through the grey fog that legend

attributes to the west of Cornwall. Whether this

is so or not, the effect upon the Knights has been

the exact opposite for, with their advent, there came

over their work an utter change in both their out-

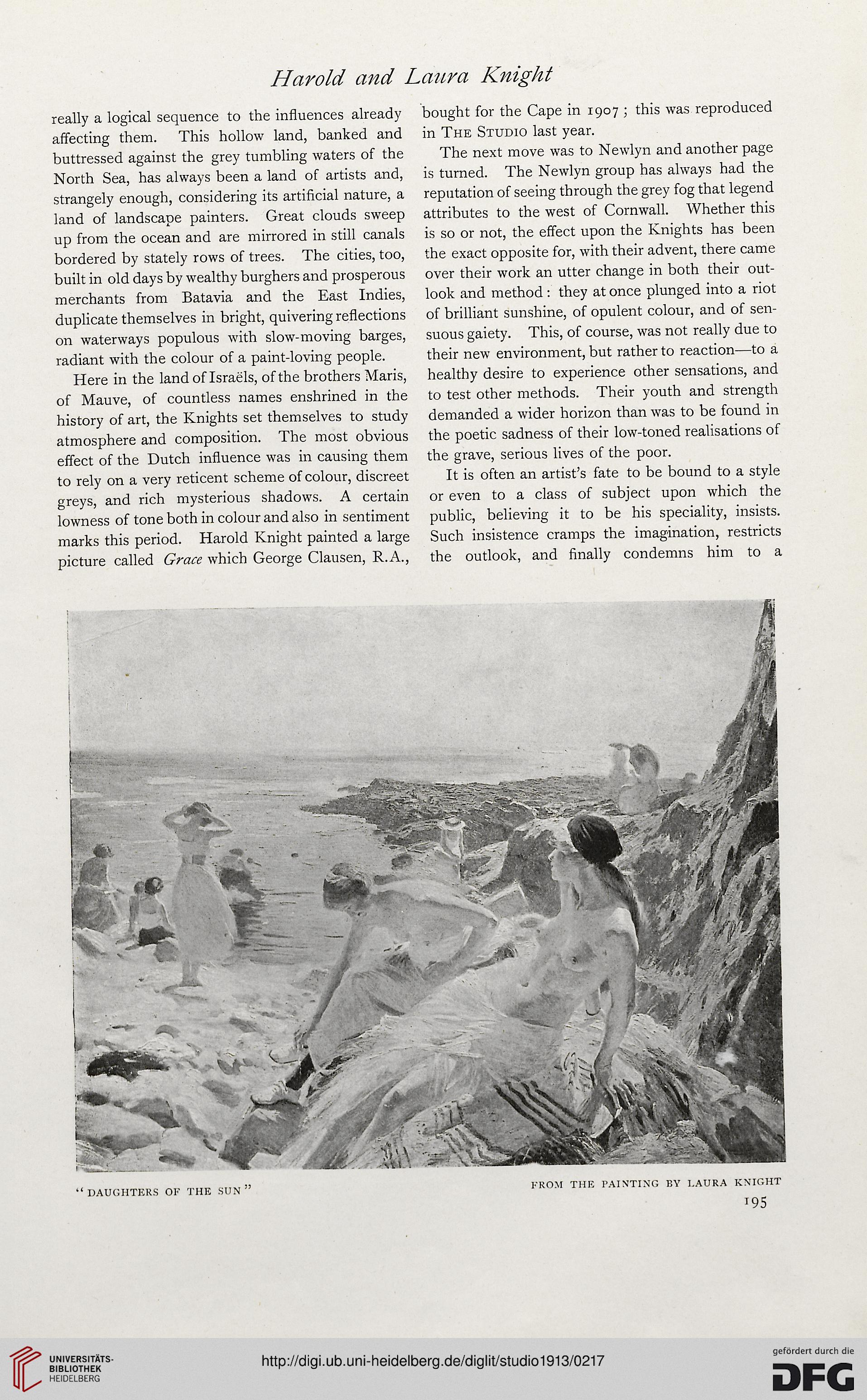

look and method : they at once plunged into a riot

of brilliant sunshine, of opulent colour, and of sen-

suous gaiety. This, of course, was not really due to

their new environment, but rather to reaction—to a

healthy desire to experience other sensations, and

to test other methods. Their youth and strength

demanded a wider horizon than was to be found in

the poetic sadness of their low-toned realisations of

the grave, serious lives of the poor.

It is often an artist’s fate to be bound to a style

or even to a class of subject upon which the

public, believing it to be his speciality, insists.

Such insistence cramps the imagination, restricts

the outlook, and finally condemns him to a

really a logical sequence to the influences already

affecting them. This hollow land, banked and

buttressed against the grey tumbling waters of the

North Sea, has always been a land of artists and,

strangely enough, considering its artificial nature, a

land of landscape painters. Great clouds sweep

up from the ocean and are mirrored in still canals

bordered by stately rows of trees. The cities, too,

built in old days by wealthy burghers and prosperous

merchants from Batavia and the East Indies,

duplicate themselves in bright, quivering reflections

on waterways populous with slow-moving barges,

radiant with the colour of a paint-loving people.

Here in the land of Israels, of the brothers Maris,

of Mauve, of countless names enshrined in the

history of art, the Knights set themselves to study

atmosphere and composition. The most obvious

effect of the Dutch influence was in causing them

to rely on a very reticent scheme of colour, discreet

greys, and rich mysterious shadows. A certain

lowness of tone both in colour and also in sentiment

marks this period. Harold Knight painted a large

picture called Grace which George Clausen, R.A.,

bought for the Cape in 1907 ; this was reproduced

in The Studio last year.

The next move was to Newlyn and another page

is turned. The Newlyn group has always had the

reputation of seeing through the grey fog that legend

attributes to the west of Cornwall. Whether this

is so or not, the effect upon the Knights has been

the exact opposite for, with their advent, there came

over their work an utter change in both their out-

look and method : they at once plunged into a riot

of brilliant sunshine, of opulent colour, and of sen-

suous gaiety. This, of course, was not really due to

their new environment, but rather to reaction—to a

healthy desire to experience other sensations, and

to test other methods. Their youth and strength

demanded a wider horizon than was to be found in

the poetic sadness of their low-toned realisations of

the grave, serious lives of the poor.

It is often an artist’s fate to be bound to a style

or even to a class of subject upon which the

public, believing it to be his speciality, insists.

Such insistence cramps the imagination, restricts

the outlook, and finally condemns him to a