The Paris Salon of Fifty Years Ago

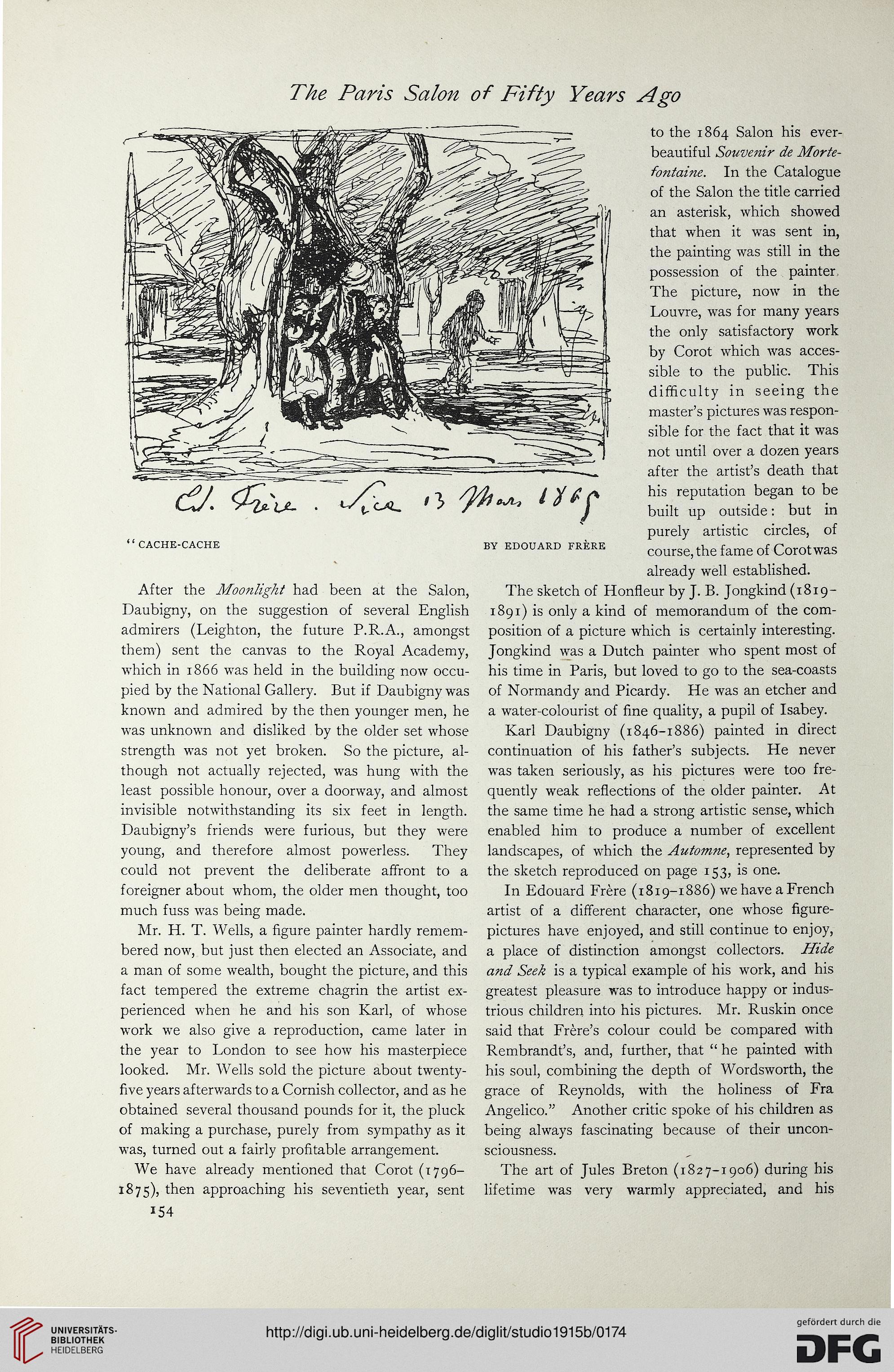

“ CACHE-CACHE

After the Moonlight had been at the Salon,

Daubigny, on the suggestion of several English

admirers (Leighton, the future P.R.A., amongst

them) sent the canvas to the Royal Academy,

which in 1866 was held in the building now occu-

pied by the National Gallery. But if Daubigny was

known and admired by the then younger men, he

was unknown and disliked by the older set whose

strength was not yet broken. So the picture, al-

though not actually rejected, was hung with the

least possible honour, over a doorway, and almost

invisible notwithstanding its six feet in length.

Daubigny’s friends were furious, but they were

young, and therefore almost powerless. They

could not prevent the deliberate affront to a

foreigner about whom, the older men thought, too

much fuss was being made.

Mr. H. T. Wells, a figure painter hardly remem-

bered now, but just then elected an Associate, and

a man of some wealth, bought the picture, and this

fact tempered the extreme chagrin the artist ex-

perienced when he and his son Karl, of whose

work we also give a reproduction, came later in

the year to London to see how his masterpiece

looked. Mr. Wells sold the picture about twenty-

five years afterwards to a Cornish collector, and as he

obtained several thousand pounds for it, the pluck

of making a purchase, purely from sympathy as it

was, turned out a fairly profitable arrangement.

We have already mentioned that Corot (1796-

1875), then approaching his seventieth year, sent

*54

to the 1864 Salon his ever-

beautiful Souvenir de Morte-

fontaine. In the Catalogue

of the Salon the title carried

an asterisk, which showed

that when it was sent in,

the painting was still in the

possession of the painter

The picture, now in the

Louvre, was for many years

the only satisfactory work

by Corot which was acces-

sible to the public. This

difficulty in seeing the

master’s pictures was respon-

sible for the fact that it was

not until over a dozen years

after the artist’s death that

his reputation began to be

built up outside: but in

purely artistic circles, of

course, the fame of Corot was

already well established.

The sketch of Honfleur by J. B. Jongkind (1819-

1891) is only a kind of memorandum of the com-

position of a picture which is certainly interesting.

Jongkind was a Dutch painter who spent most of

his time in Baris, but loved to go to the sea-coasts

of Normandy and Picardy. He was an etcher and

a water-colourist of fine quality, a pupil of Isabey.

Karl Daubigny (1846-1886) painted in direct

continuation of his father’s subjects. He never

was taken seriously, as his pictures were too fre-

quently weak reflections of the older painter. At

the same time he had a strong artistic sense, which

enabled him to produce a number of excellent

landscapes, of which the Automne, represented by

the sketch reproduced on page 153, is one.

In Edouard Frere (1819-1886) we have a French

artist of a different character, one whose figure-

pictures have enjoyed, and still continue to enjoy,

a place of distinction amongst collectors. Hide

and Seek is a typical example of his work, and his

greatest pleasure was to introduce happy or indus-

trious children into his pictures. Mr. Ruskin once

said that Frere’s colour could be compared with

Rembrandt’s, and, further, that “ he painted with

his soul, combining the depth of Wordsworth, the

grace of Reynolds, with the holiness of Fra

Angelico.” Another critic spoke of his children as

being always fascinating because of their uncon-

sciousness.

The art of Jules Breton (1827-1906) during his

lifetime was very warmly appreciated, and his

“ CACHE-CACHE

After the Moonlight had been at the Salon,

Daubigny, on the suggestion of several English

admirers (Leighton, the future P.R.A., amongst

them) sent the canvas to the Royal Academy,

which in 1866 was held in the building now occu-

pied by the National Gallery. But if Daubigny was

known and admired by the then younger men, he

was unknown and disliked by the older set whose

strength was not yet broken. So the picture, al-

though not actually rejected, was hung with the

least possible honour, over a doorway, and almost

invisible notwithstanding its six feet in length.

Daubigny’s friends were furious, but they were

young, and therefore almost powerless. They

could not prevent the deliberate affront to a

foreigner about whom, the older men thought, too

much fuss was being made.

Mr. H. T. Wells, a figure painter hardly remem-

bered now, but just then elected an Associate, and

a man of some wealth, bought the picture, and this

fact tempered the extreme chagrin the artist ex-

perienced when he and his son Karl, of whose

work we also give a reproduction, came later in

the year to London to see how his masterpiece

looked. Mr. Wells sold the picture about twenty-

five years afterwards to a Cornish collector, and as he

obtained several thousand pounds for it, the pluck

of making a purchase, purely from sympathy as it

was, turned out a fairly profitable arrangement.

We have already mentioned that Corot (1796-

1875), then approaching his seventieth year, sent

*54

to the 1864 Salon his ever-

beautiful Souvenir de Morte-

fontaine. In the Catalogue

of the Salon the title carried

an asterisk, which showed

that when it was sent in,

the painting was still in the

possession of the painter

The picture, now in the

Louvre, was for many years

the only satisfactory work

by Corot which was acces-

sible to the public. This

difficulty in seeing the

master’s pictures was respon-

sible for the fact that it was

not until over a dozen years

after the artist’s death that

his reputation began to be

built up outside: but in

purely artistic circles, of

course, the fame of Corot was

already well established.

The sketch of Honfleur by J. B. Jongkind (1819-

1891) is only a kind of memorandum of the com-

position of a picture which is certainly interesting.

Jongkind was a Dutch painter who spent most of

his time in Baris, but loved to go to the sea-coasts

of Normandy and Picardy. He was an etcher and

a water-colourist of fine quality, a pupil of Isabey.

Karl Daubigny (1846-1886) painted in direct

continuation of his father’s subjects. He never

was taken seriously, as his pictures were too fre-

quently weak reflections of the older painter. At

the same time he had a strong artistic sense, which

enabled him to produce a number of excellent

landscapes, of which the Automne, represented by

the sketch reproduced on page 153, is one.

In Edouard Frere (1819-1886) we have a French

artist of a different character, one whose figure-

pictures have enjoyed, and still continue to enjoy,

a place of distinction amongst collectors. Hide

and Seek is a typical example of his work, and his

greatest pleasure was to introduce happy or indus-

trious children into his pictures. Mr. Ruskin once

said that Frere’s colour could be compared with

Rembrandt’s, and, further, that “ he painted with

his soul, combining the depth of Wordsworth, the

grace of Reynolds, with the holiness of Fra

Angelico.” Another critic spoke of his children as

being always fascinating because of their uncon-

sciousness.

The art of Jules Breton (1827-1906) during his

lifetime was very warmly appreciated, and his