The Paris Salon of Fifty Years Ago

In the year 1867, when the Great Exhibition

was held in the French metropolis, both Manet

and Courbet, who also was popularly disliked,

obtained permission to hold personal exhibitions.

A shed-like structure was erected near the Pont de

l’Alma, and there in May 1867 Manet exhibited

about fifty of his pictures, practically all he had

produced. As M. Duret relates, “the greater part

of this magnificent collection has now found its

way into various public and private collections of

note in Europe and America.” But the Parisian

public and their visitors refused to see any good in

Manet’s work, and it has remained for the present

generation to place him on the high level where he

properly belongs. The catalogue of the Exhibition

of 1867 contained a lengthy statement by Manet,

“ Reasons for holding a Private Exhibition,” setting

forth the artist’s position in a remarkable way.

The necessity to exhibit he emphasises very

strongly : “ The matter of vital concern for the

artist is to exhibit; for it happens, after some

looking at a thing, that one becomes familiar with

what was surprising, or, if you will, shocking. Little

by little it becomes understood and accepted. . . .

By exhibiting, an artist

finds friends and sup-

porters who encourage

him in his struggle.

M. Manet has no pre-

tensions either to over-

throw an established

mode of painting or to

create a new one. He

has simply tried to be

himself and not

another.”

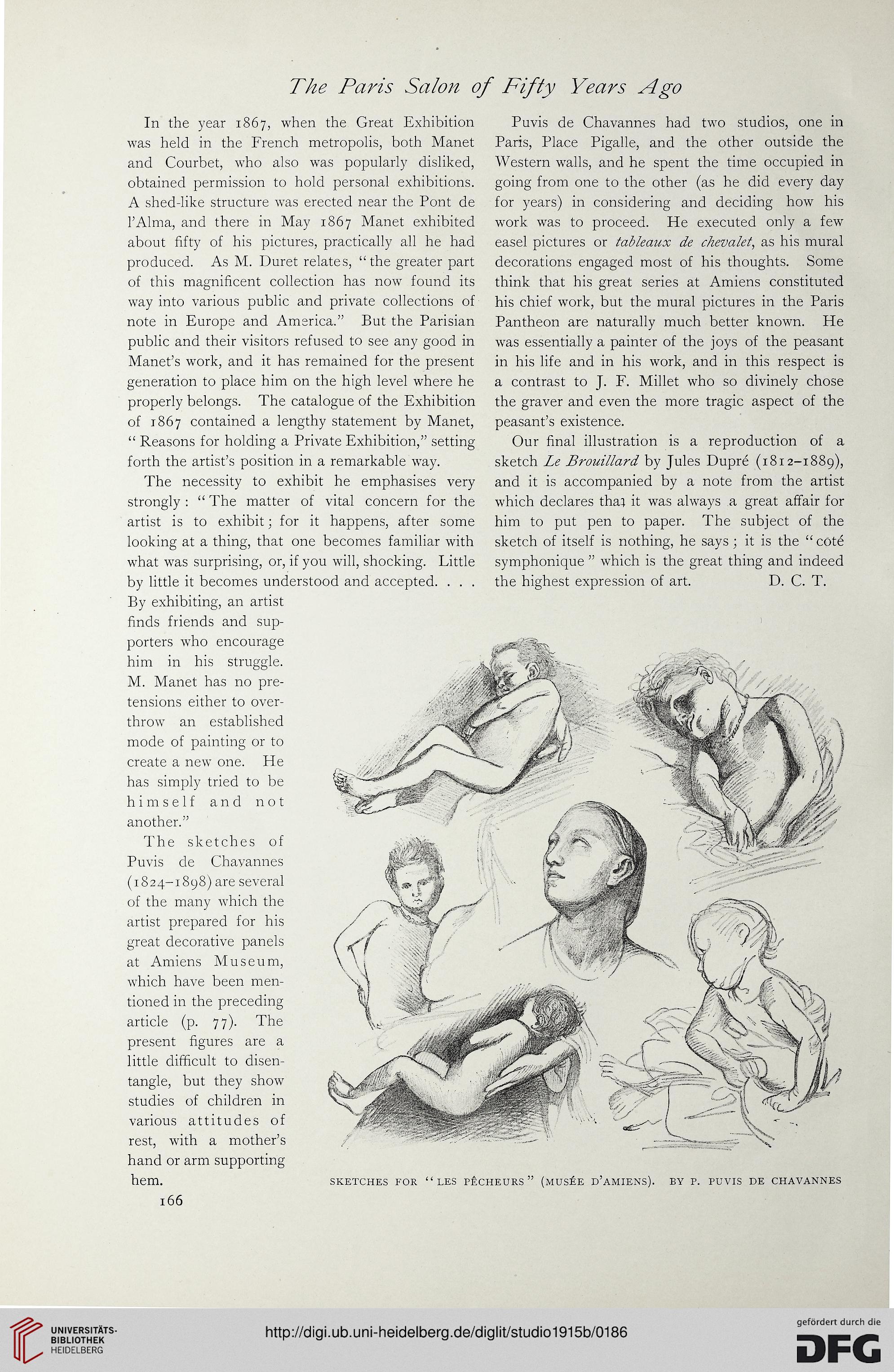

The sketches of

Puvis de Chayannes

(1824-1898) are several

of the many which the

artist prepared for his

great decorative panels

at Amiens Museum,

which have been men-

tioned in the preceding

article (p. 77). The

present figures are a

little difficult to disen-

tangle, but they show

studies of children in

various attitudes of

rest, with a mother’s

hand or arm supporting

hem. SKETCHES FOR “ LES PECHEURS” (MUSkE D’AMIENS). BY P. PUVIS DE CHAVANNES

l66

Puvis de Chavannes had two studios, one in

Paris, Place Pigalle, and the other outside the

Western walls, and he spent the time occupied in

going from one to the other (as he did every day

for years) in considering and deciding how his

work was to proceed. He executed only a few

easel pictures or tableaux de chevalet, as his mural

decorations engaged most of his thoughts. Some

think that his great series at Amiens constituted

his chief work, but the mural pictures in the Paris

Pantheon are naturally much better known. He

was essentially a painter of the joys of the peasant

in his life and in his work, and in this respect is

a contrast to J. F. Millet who so divinely chose

the graver and even the more tragic aspect of the

peasant’s existence.

Our final illustration is a reproduction of a

sketch Le Brouillard by Jules Dupre (1812-1889),

and it is accompanied by a note from the artist

which declares that it was always a great affair for

him to put pen to paper. The subject of the

sketch of itself is nothing, he says ; it is the “cote

symphonique ” which is the great thing and indeed

the highest expression of art. D. C. T.

In the year 1867, when the Great Exhibition

was held in the French metropolis, both Manet

and Courbet, who also was popularly disliked,

obtained permission to hold personal exhibitions.

A shed-like structure was erected near the Pont de

l’Alma, and there in May 1867 Manet exhibited

about fifty of his pictures, practically all he had

produced. As M. Duret relates, “the greater part

of this magnificent collection has now found its

way into various public and private collections of

note in Europe and America.” But the Parisian

public and their visitors refused to see any good in

Manet’s work, and it has remained for the present

generation to place him on the high level where he

properly belongs. The catalogue of the Exhibition

of 1867 contained a lengthy statement by Manet,

“ Reasons for holding a Private Exhibition,” setting

forth the artist’s position in a remarkable way.

The necessity to exhibit he emphasises very

strongly : “ The matter of vital concern for the

artist is to exhibit; for it happens, after some

looking at a thing, that one becomes familiar with

what was surprising, or, if you will, shocking. Little

by little it becomes understood and accepted. . . .

By exhibiting, an artist

finds friends and sup-

porters who encourage

him in his struggle.

M. Manet has no pre-

tensions either to over-

throw an established

mode of painting or to

create a new one. He

has simply tried to be

himself and not

another.”

The sketches of

Puvis de Chayannes

(1824-1898) are several

of the many which the

artist prepared for his

great decorative panels

at Amiens Museum,

which have been men-

tioned in the preceding

article (p. 77). The

present figures are a

little difficult to disen-

tangle, but they show

studies of children in

various attitudes of

rest, with a mother’s

hand or arm supporting

hem. SKETCHES FOR “ LES PECHEURS” (MUSkE D’AMIENS). BY P. PUVIS DE CHAVANNES

l66

Puvis de Chavannes had two studios, one in

Paris, Place Pigalle, and the other outside the

Western walls, and he spent the time occupied in

going from one to the other (as he did every day

for years) in considering and deciding how his

work was to proceed. He executed only a few

easel pictures or tableaux de chevalet, as his mural

decorations engaged most of his thoughts. Some

think that his great series at Amiens constituted

his chief work, but the mural pictures in the Paris

Pantheon are naturally much better known. He

was essentially a painter of the joys of the peasant

in his life and in his work, and in this respect is

a contrast to J. F. Millet who so divinely chose

the graver and even the more tragic aspect of the

peasant’s existence.

Our final illustration is a reproduction of a

sketch Le Brouillard by Jules Dupre (1812-1889),

and it is accompanied by a note from the artist

which declares that it was always a great affair for

him to put pen to paper. The subject of the

sketch of itself is nothing, he says ; it is the “cote

symphonique ” which is the great thing and indeed

the highest expression of art. D. C. T.