Three Painters of the New York School

word “ unity ” is interesting, since he implies by it

a unity of character; one may gather that he has

not much faith in art for its own sake. “ Colours

are beautiful when they are significant, lines are

beautiful when they are significant,” declares Mr.

Henri. This conception is related to that of the

Chinese painter who called his art “ the movement

of his spirit in the rhythm of things,” or that of

another who defined art as “ mind on the point of a

brush.”

It is this quality of thought indefinably perme-

ating a work of art that, in the case of a portrait,

makes a universal type of what otherwise might

be a purely local character. Millet’s dictum of the

type being “ the most powerful truth ” has sunk

deep into the fertile American soil. Mr. Henri’s

studies of types have this impetus behind them.

They arouse other than merely retinal impressions.

Mr. Henri has drawn upon Spain and Holland as

well as upon America for his material. It is through

his democratic humanism, his exclusion of feudal

themes, and his vigorous mental attitude and faith

that he is an American. He is more American than

Whistler, less than Winslow Homer.

Mr. Henri’s large gallery of types presents an ex-

cellent opportunity for testing his ideas on “ specific

technique—the method that belongs to the idea,”

which means simply that the style should vary with

the subject. This is by no means a new idea—it was

the method of the Chinese painters; but what Mr.

Henri desires to impress upon one is that the

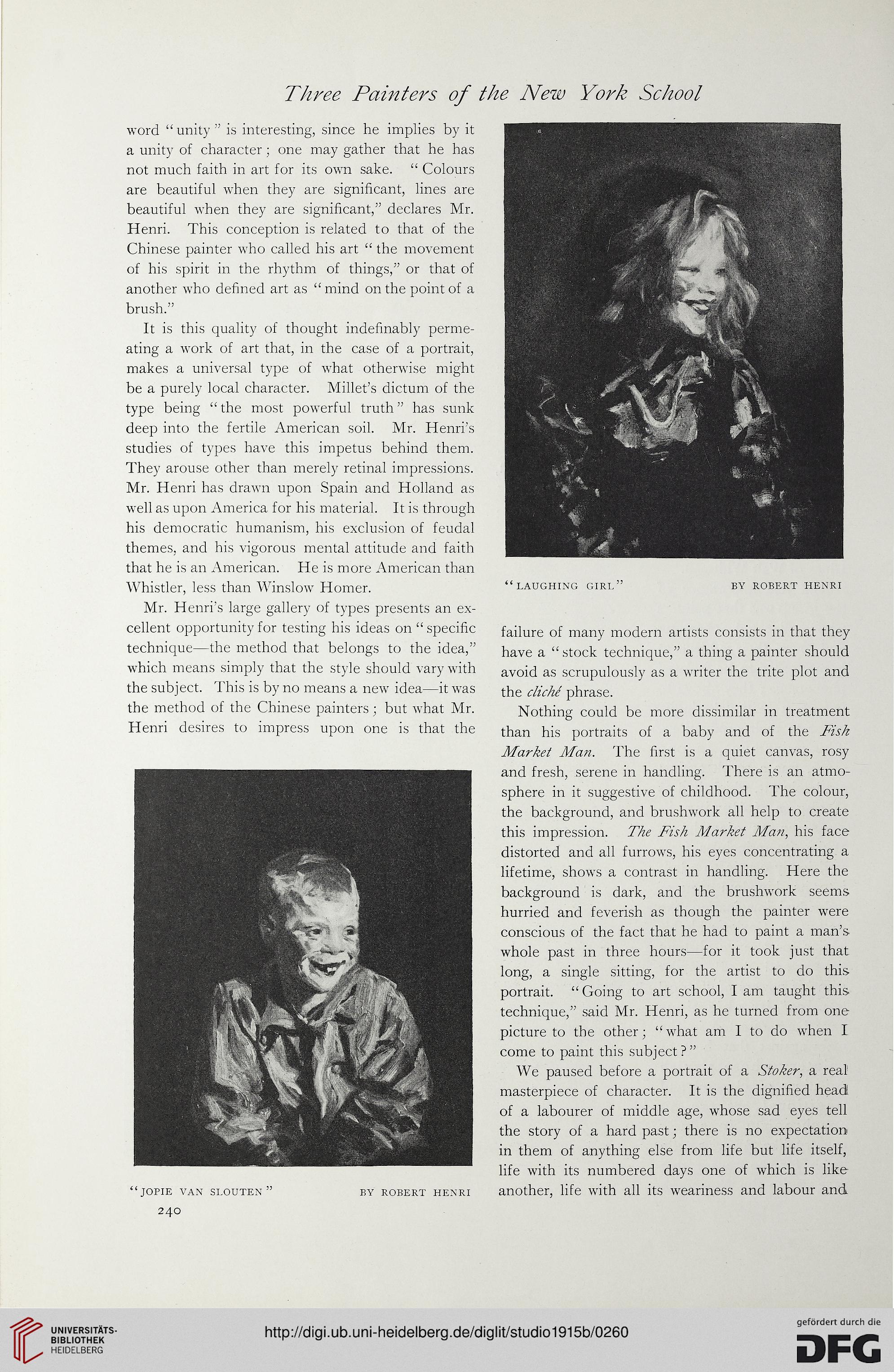

“JOPIE VAN SLOUTEN ” BY ROBERT HENRI

“LAUGHING GIRL” BY ROBERT HENRI

failure of many modern artists consists in that they

have a “stock technique,” a thing a painter should

avoid as scrupulously as a writer the trite plot and

the cliche phrase.

Nothing could be more dissimilar in treatment

than his portraits of a baby and of the Fish

Market Man. The first is a quiet canvas, rosy

and fresh, serene in handling. There is an atmo-

sphere in it suggestive of childhood. The colour,

the background, and brushwork all help to create

this impression. The Fish Market Man, his face

distorted and all furrows, his eyes concentrating a

lifetime, shows a contrast in handling. Here the

background is dark, and the brushwork seems

hurried and feverish as though the painter were

conscious of the fact that he had to paint a man’s

whole past in three hours—for it took just that

long, a single sitting, for the artist to do this

portrait. “ Going to art school, I am taught this

technique,” said Mr. Henri, as he turned from one

picture to the other; “what am I to do when I

come to paint this subject?”

We paused before a portrait of a Stoker, a real

masterpiece of character. It is the dignified head

of a labourer of middle age, whose sad eyes tell

the story of a hard past; there is no expectation

in them of anything else from life but life itself,

life with its numbered days one of which is like

another, life with all its weariness and labour and

240

word “ unity ” is interesting, since he implies by it

a unity of character; one may gather that he has

not much faith in art for its own sake. “ Colours

are beautiful when they are significant, lines are

beautiful when they are significant,” declares Mr.

Henri. This conception is related to that of the

Chinese painter who called his art “ the movement

of his spirit in the rhythm of things,” or that of

another who defined art as “ mind on the point of a

brush.”

It is this quality of thought indefinably perme-

ating a work of art that, in the case of a portrait,

makes a universal type of what otherwise might

be a purely local character. Millet’s dictum of the

type being “ the most powerful truth ” has sunk

deep into the fertile American soil. Mr. Henri’s

studies of types have this impetus behind them.

They arouse other than merely retinal impressions.

Mr. Henri has drawn upon Spain and Holland as

well as upon America for his material. It is through

his democratic humanism, his exclusion of feudal

themes, and his vigorous mental attitude and faith

that he is an American. He is more American than

Whistler, less than Winslow Homer.

Mr. Henri’s large gallery of types presents an ex-

cellent opportunity for testing his ideas on “ specific

technique—the method that belongs to the idea,”

which means simply that the style should vary with

the subject. This is by no means a new idea—it was

the method of the Chinese painters; but what Mr.

Henri desires to impress upon one is that the

“JOPIE VAN SLOUTEN ” BY ROBERT HENRI

“LAUGHING GIRL” BY ROBERT HENRI

failure of many modern artists consists in that they

have a “stock technique,” a thing a painter should

avoid as scrupulously as a writer the trite plot and

the cliche phrase.

Nothing could be more dissimilar in treatment

than his portraits of a baby and of the Fish

Market Man. The first is a quiet canvas, rosy

and fresh, serene in handling. There is an atmo-

sphere in it suggestive of childhood. The colour,

the background, and brushwork all help to create

this impression. The Fish Market Man, his face

distorted and all furrows, his eyes concentrating a

lifetime, shows a contrast in handling. Here the

background is dark, and the brushwork seems

hurried and feverish as though the painter were

conscious of the fact that he had to paint a man’s

whole past in three hours—for it took just that

long, a single sitting, for the artist to do this

portrait. “ Going to art school, I am taught this

technique,” said Mr. Henri, as he turned from one

picture to the other; “what am I to do when I

come to paint this subject?”

We paused before a portrait of a Stoker, a real

masterpiece of character. It is the dignified head

of a labourer of middle age, whose sad eyes tell

the story of a hard past; there is no expectation

in them of anything else from life but life itself,

life with its numbered days one of which is like

another, life with all its weariness and labour and

240