Modern French Pictures at the National Gallery

Those who immensely admire Daumier’s art,

which is now so much in fashion, will no doubt

esteem his painting, Don Quixote and Sancho

Panza, more than his oil-sketch of Daubigny.

I cannot write as one who can see in the forced

theatrical vehemence of Daumier the greatest

achievement of the modern world. Yet this

painting of Don Quixote is one of the most

representative of his important canvases, and

it vindicates the scope of the collection that we

should find it beside the Manets and the Renoir.

Of the later Impressionists none is more

interesting than Vuillard, and Vuillard’s The

Mantelpiece must be counted among master-

pieces of still-life.

Forain remains in his painting The Law Courts,

a graphic artist rather than a painter. There is

a purely literary flavour in his art; the moralities

are surprised there, as in Hogarth’s work.

But in this evocation of moral atmosphere

Forain’s art is far removed from that of the

Impressionists. To them life does not merely

mean human life and its surroundings. Their

pantheism does not only discover a spirit in

nature; it also regards as nature every phase

of life in the recesses of the town. It will not

regard one aspect of life as more noble, more

worthy of representation, than another—not

from blindness to ideal beauty but from an atti-

tude of reverence to every manifestation of life.

The virtue of Impressionism was its exquisite

sensibility ; the mirror that it held to nature

was the most sensitive that has ever yet received

an image on its surface. But the greatest

Impressionist art was not merely receptive, it

knew what it wished to retain. It could not

bear the thought that beauty involved in

transient conditions would pass away with them

as if it had never been. It strove to detain the

elements that went to make the passing show

enchanting, desiring that, as its tenement

crumbled to dust, the spirit of the hour should

enter into immortal life in art.

In forming his collection of continental

pictures Sir Hugh Lane did not confine himself

to French pictures. He took pains to secure

a typical example of the work of the Belgian

interior painter Stevens; while, with Mr. J. S.

Sargent, he greatly admired the art of Mancini,

and acquired several works by that painter.

In representing French art he cast back as far

as Ingres, with the head of the Due d’Orleans—

a study for the full-length at Versailles.

As I am adding the last words to this article

the news comes to hand of the death of M. Degas,

at the age of eighty-three.

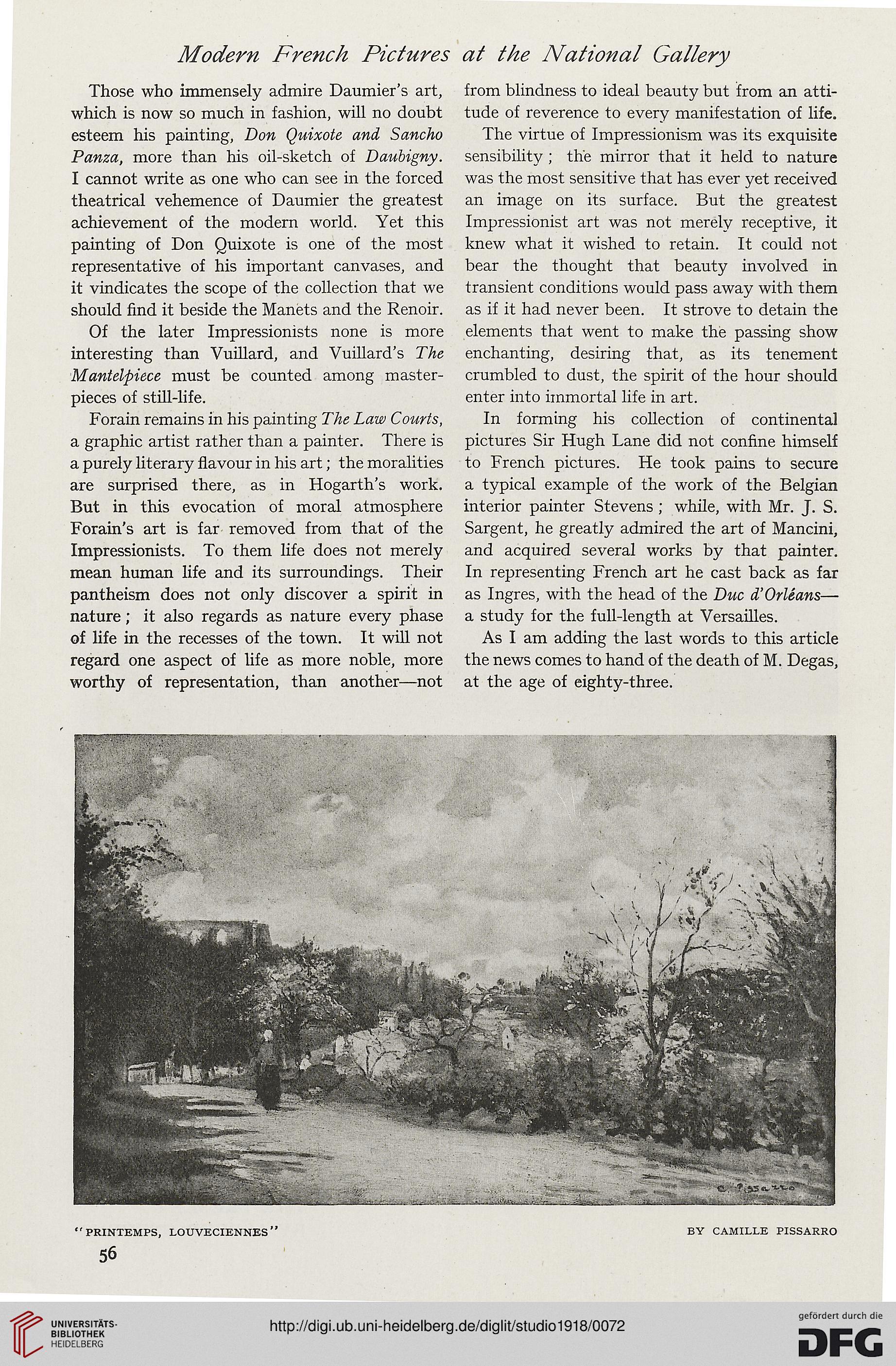

BY CAMILLE PISSARRO

Those who immensely admire Daumier’s art,

which is now so much in fashion, will no doubt

esteem his painting, Don Quixote and Sancho

Panza, more than his oil-sketch of Daubigny.

I cannot write as one who can see in the forced

theatrical vehemence of Daumier the greatest

achievement of the modern world. Yet this

painting of Don Quixote is one of the most

representative of his important canvases, and

it vindicates the scope of the collection that we

should find it beside the Manets and the Renoir.

Of the later Impressionists none is more

interesting than Vuillard, and Vuillard’s The

Mantelpiece must be counted among master-

pieces of still-life.

Forain remains in his painting The Law Courts,

a graphic artist rather than a painter. There is

a purely literary flavour in his art; the moralities

are surprised there, as in Hogarth’s work.

But in this evocation of moral atmosphere

Forain’s art is far removed from that of the

Impressionists. To them life does not merely

mean human life and its surroundings. Their

pantheism does not only discover a spirit in

nature; it also regards as nature every phase

of life in the recesses of the town. It will not

regard one aspect of life as more noble, more

worthy of representation, than another—not

from blindness to ideal beauty but from an atti-

tude of reverence to every manifestation of life.

The virtue of Impressionism was its exquisite

sensibility ; the mirror that it held to nature

was the most sensitive that has ever yet received

an image on its surface. But the greatest

Impressionist art was not merely receptive, it

knew what it wished to retain. It could not

bear the thought that beauty involved in

transient conditions would pass away with them

as if it had never been. It strove to detain the

elements that went to make the passing show

enchanting, desiring that, as its tenement

crumbled to dust, the spirit of the hour should

enter into immortal life in art.

In forming his collection of continental

pictures Sir Hugh Lane did not confine himself

to French pictures. He took pains to secure

a typical example of the work of the Belgian

interior painter Stevens; while, with Mr. J. S.

Sargent, he greatly admired the art of Mancini,

and acquired several works by that painter.

In representing French art he cast back as far

as Ingres, with the head of the Due d’Orleans—

a study for the full-length at Versailles.

As I am adding the last words to this article

the news comes to hand of the death of M. Degas,

at the age of eighty-three.

BY CAMILLE PISSARRO