Introduction

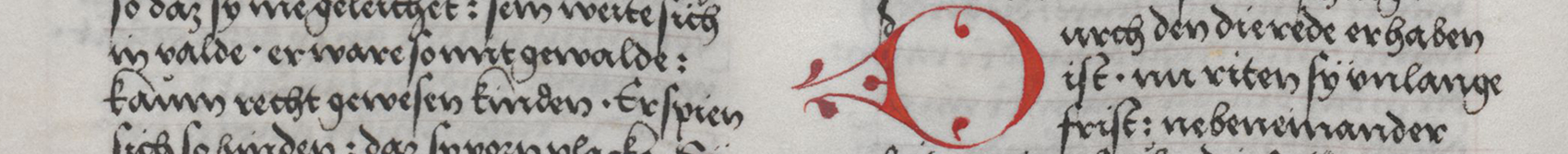

Hartmann's von Aue Erek has survived complete in only one manuscript, which moreover was written very late. It is the so-called Ambraser Heldenbuch, commissioned by Emperor Maximilian I in the first decade of the 16th century and completed in 1516/17. There the Erek stands behind the Iwein. Two fragments from the 13th and one from the 14th century complete the panorama of surviving texts.

However, this manuscript transmission is only apparently simple. For in one of the fragments (W), part of the text does not correspond to that of the only complete manuscript; it seems to be a partially different version of the romance. This has been called (because of its dialect) the Middle German Erek. Later, another fragment (Z) was discovered which also contains a different version of a small part of the text and has been attributed to this Middle German Erek. However, much is still unclear in this context, especially whether this can be considered a new text. This is one of the reasons why these two fragments are also included in the Erek – digital project.

The manuscript transmission is made more complex by the fact that the only complete manuscript copies, under the same heading but before the actual Erek-story begins, an Arthurian adventure written in 995 verses about a magic cloak. Since this first part does not correspond to Hartmann's source, the Erec of Chrétien de Troyes, and since there is also a small jump in the plot at the intersection between the two segments, it has been assumed since the 19th century that two independent texts were connected here. Since then, the Erek has always been edited without the prologue, as if the beginning of the story had not survived. However, this must be considered wrong, for the scribe of the main manuscript A made it clear through a heading of several lines that for him the two narrative strands belonged together. From an interpretative point of view, one may well come to the conclusion that the two parts were not composed by the same author; but from an editorial point of view, there is no way around reproducing the complete text of the only extant manuscript.

The edition by Timo Felber, Andreas Hammer and Victor Millet of 2017 (2nd edition 2022) took these circumstances into account and edited the Erek strictly according to manuscript A, with the addition of all fragments. An active debate has unfolded since then, both around the problem whether the so-called Mantel belongs to the main text, and around the question whether the text of this very late manuscript can still be attributed to Hartmann von Aue. The present digital edition follows the path of the 2017 edition. Like it (and like the other digital editions in Hartmann von Aue –digital), we are not offering a critical edition of Erek. The aim is not to recover a supposed text by Hartmann von Aue; that purpose was followed for a century and a half in the editions of Moritz Haupt and Albert Leitzmann and their successors. Rather, in this edition the text of the only manuscript will be reproduced. In doing so, we omit a conversion into a 'standard Middle High German', which was common in the older editions, and which was also an important gateway for many unnecessary corrections.

Erek – digital aims to edit the Erek's extant testimonies in their current form and in greater breadth and to make them readable. The aim of this project is thus to highlight textual variation in the tradition of Erek and to show how this romance has been read and interpreted over the centuries.

Since the first edition by Moritz Haupt, the hero of this romance has been known in research as 'Erec'. It should be noted, however, that not a single manuscript or fragment writes the name with ⟨c⟩ at the end; usually both the textual witnesses of Erek and mentions of this figure in other works write the name with ⟨k⟩, sometimes also with ⟨ck⟩ at the end. Manuscript A mostly writes it with a ⟨ck⟩, and that is why Felber, Hammer and Millet named the text Ereck in their edition. However, since this latter form belongs more to early new high German, we have decided not to use it here. The manuscripts mostly spell it ⟨Erek⟩ and therefore the francophone form with ⟨c⟩ seems unjustified.